Oscillator Ising Machines Take Quantum Computation for a Classical Spin

Twenty years into the 21st century the demand for computational power is outpacing supply at an ever-increasing rate. From global pandemics that require rapid-response drug designs, to smart grids, self-driving vehicles, artificial intelligence and machine learning, scientists are scrambling to boost current computational capabilities until quantum computing becomes a practical reality.

Especially challenging are combinatorial optimization problems. The textbook example of such problems is solving for the shortest route between a given number of cities that starts and ends at the same place. This “Travelling Salesman Problem” becomes exponentially more difficult as the number of cities increases and the combinations of possible routes become astronomical.

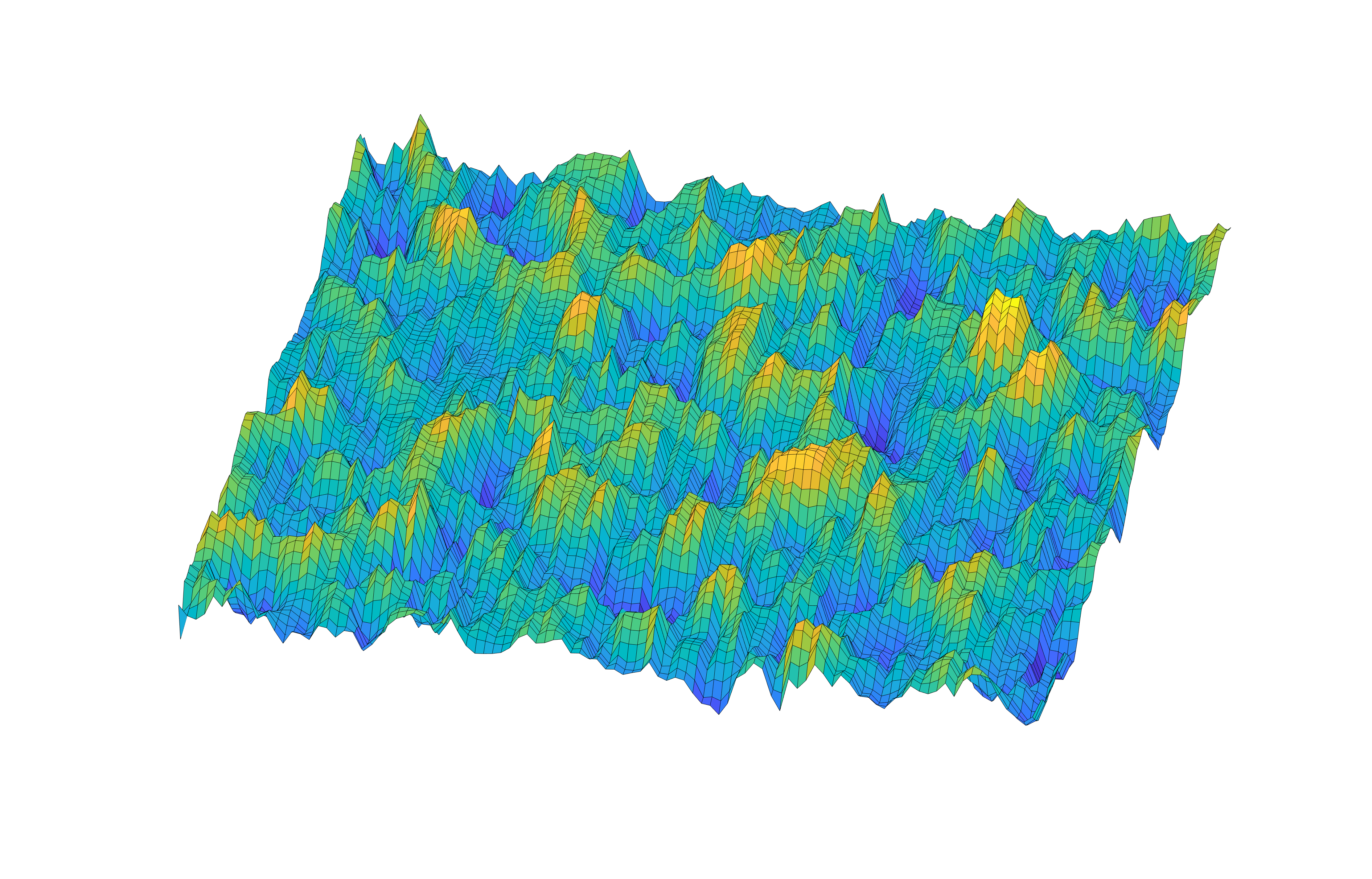

Bakar Fellow Jaijeet Roychowdhury, Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences, led a breakthrough that enables combinatorial optimization problems involving millions of possible outcomes to be solved with quantum computer-type speed and efficiency using conventional Complementary Metal–Oxide–Semiconductor (CMOS) integrated circuitry. His Oscillator Ising Machines (OIMs) encode combinatorial optimization problems as an “energy landscape” of magnetic spins – a quantum property of oscillating electrons – in which the solution is determined by the lowest energy configuration of synchronized or coupled oscillator spins.

Synchronization of electronic oscillations enables OIMs to solve combinatorial optimization problems on relatively inexpensive, low-power miniaturized CMOS chips without costly technical challenges, such as cryogenic operational temperatures, that are required by other combinatorial optimization strategies.

Q: You have said the key to the success of your OIMs is appropriately designed oscillators. What makes for an “appropriate” design?

A: Unlike standard electronic oscillator designs, the oscillators in our OIM chip are designed with injection locking properties that promote effective coupling. Our choice of couplings between oscillators is also important. While relative coupling values are set by the combinatorial optimization problem being solved, there is freedom in choosing absolute values. These values need to be informed by the nature of the oscillators, as well as CMOS technology considerations. Another important aspect of appropriate design is the choice of the synchronization signal that takes each oscillator from a digital to an analog operational mode and back again.

Q: Did you draw your inspiration for synchronizing the electronic oscillators in your OIMs from nature’s use of synchronized oscillations to optimize energy efficiencies?

A: Yes and no. I’ve been interested in oscillators since childhood when I tried to fix my grandmother's vacuum tube radio. My attempt was unsuccessful but got me interested in figuring out how oscillators work. Over the years I learned that the standard explanations for electronic oscillators are overly simplistic and actually obviously wrong in some respects. In our group we realized that injection locking in biological synchronization, such as the synchronized flashing of fireflies, can be applied to electronics to make von-Neumann computers with oscillators instead of standard registers. The discovery of an energy aspect to injection locking was arguably the key step that engendered OIMs.

Q: Is the lowest energy configuration of spins in an OIM energy landscape analogous to the minimum travel distance in the Travelling Salesperson Problem (TSP)?

A: Yes, the minimum distance for the TSP corresponds to the minimum energy configuration in our OIM formulation, but to find the OIM solution the TSP must be recast in Ising form. This means that solving for N cities in the TSP problem requires N2 spins in the Ising form. For example, if you wanted to travel between 100 cities, you need to solve an Ising problem with about 10,000 spins; if you wanted to travel between 10,000 cities, then you would need 100 million Ising spins! That’s a large number but scaling to large numbers of spins is one of the key advantages of OIMs because you can put billions of CMOS transistors on a small chip. The processor chips in every computer and cellphone contain that many transistors and OIM chips with 100 million or more spins should be relatively easy to build once we’ve shown the way with smaller versions.

Q: What do you see as the most immediate applications for OIMs?

A: One of the nice things about our OIMs is that they don't care what application domain the problem they are solving comes from. So long as the problem is in Ising form and the OIMs can be programmed with it, they will work. Furthermore, virtually every combinatorial optimization problem, regardless of where it arises, can be cast in Ising form. That said, a general rule in research is that it is extremely helpful to focus on solving a particular end problem. Like much of the Ising community, we’ve have been focusing on the MAX-CUT problem in graphs, for which there are widely available benchmarks. We’re also looking at combinatorial optimization problems in communications.

Q: How have you been using your Bakar Fellowship to advance OIMs research?

A: The Bakar Fellowship has been instrumental in allowing us to focus on designing OIM chips, and also on developing communication applications.

The Bakar Fellows Program supports innovative research by early career faculty at UC Berkeley with a special focus on projects that hold commercial promise. For more information, see http://bakarfellows.berkeley.edu.