A New Test Can See -- Almost Literally -- Infectious Bacteria

Urinary tract infections, or UTIs, are one of the most common bacterial infections in the world. With some serious exceptions, they can usually be treated with off-the-shelf prescription antibiotics, and since the symptoms are easily recognized, physicians commonly prescribe antibiotics without waiting for a lab test. The infections are usually resolved within a week.

But up to 20 percent of UTI infections – as many as 30 million a year worldwide – don’t respond to conventional antibiotics. These are often caused by a particularly resistant microbe known as ESBL-producing bacteria.

ESBL infections must be treated with stronger antibiotics, usually given intravenously, to prevent the bacteria from infecting other parts of the body. The sooner the treatment the better, but up to now there has been no way to make a quick diagnosis.

Niren Murthy, professor of bioengineering, and colleagues have developed a 30-minute, low-tech test, called DETECT, to identify ESBL-producing bacteria on a patient’s first visit to the doctor. With support as a 2019-2020 Bakar Fellow, Murthy and his team are carrying out more research to get DETECT into the hands of physicians.

He explained his new technology and why it is needed.

Q. How serious are ESBL bacterial infections?

A. Very serious. If they aren’t treated with the right antibiotics, they can spread to the kidney, sometimes causing a permanent decrease in kidney function, and they can lead to sepsis – a very dangerous infection in the blood.

Q. How long does it take for an ESBL-producing bacterial infection to go from very irritating to potentially very serious?

A. Typically two to three weeks

Q. But how long does it usually take to detect?A.

That’s the problem. If a doctor assumes that a UTI is the garden-variety type, as most are, and prescribes a common antibiotic, a patient who actually has an ESBL-producing bacterial infection will likely return with worsening symptoms. The physician will then order a lab test to find out what the bug is. It could take one or two weeks from the initial visit to get confirmation of a serious infection. And even if the doctor orders a lab test right away on the first visit, it’s still four or five days before the ESBL infection is confirmed.

Q: How would your test be used?

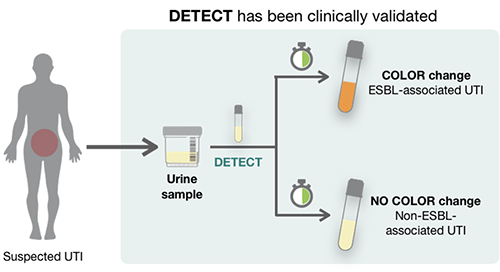

A: The test can be done right at the first point of treatment, so if a patient turns out to have an ESBL-producing bacteria, the doctor can skip the common antibiotics, and prescribe the stronger ones right away. That will spare the patient a week of increasing misery and prevent the infection from becoming more serious.

Q. How is the test carried out?

A. It involves adding a couple of reagents to a urine sample. If ESBL-producing bacteria are present, the sample changes color.

Q. Why hasn’t a quick test like this been developed before?

A. ESBL-producing bacteria are in small numbers in a urine sample. The current tests aren’t sensitive enough to detect them.

The reason the bacteria are highly resistant is because they have enzymes that digest antibiotics. Our test uses two molecules that we developed. The first looks like an antibiotic to the bacteria. The second molecule is an enzyme called papain. When the bacteria attack the first molecule, it activates papain, generating approximately 40,000 papain enzymes.

It is much easier to detect 40,000 enzyme molecules than the relatively small number of bacteria in the urine sample. The signal is greatly amplified, and the test is very sensitive. We devised the test so the sample changes color in the presence of thousands of the papain enzymes.

Q. How close is the DETECT test to commercialization?

A. We received a Bakar Fellows Spark Award, which supports research to move this point-of-care diagnostic closer to clinical trials. A former postdoc in the lab, Tara deBoer, has formed a company called Bioamp Diagnostics that is licensing DETECT. They are starting to do clinical validation studies. We have also been collaborating with Lee Riley, professor epidemiology and infectious diseases at Berkeley.

The Spark award will also support our work on developing second and third generation probes to detect all known ESBL variants. And we hope the DETECT strategy can be applied to detect enzymes in other kinds of bacteria -- not only in infectious diseases, but also to identify water impurities, for example. It can become powerful diagnostic tool.

The Bakar Fellows Program supports innovative research by early career faculty at UC Berkeley with a special focus on projects that hold commercial promise. For more information, see http://bakarfellows.berkeley.edu.