A New Recipe for Construction

A house built on salt would attract few buyers in earthquake-prone California — or anywhere for that matter. But a house built of salt may be another story. If architect Ronald Rael’s research stays on track, salt, sawdust — even pulverized tires — may some day provide the raw material for full-blown construction.

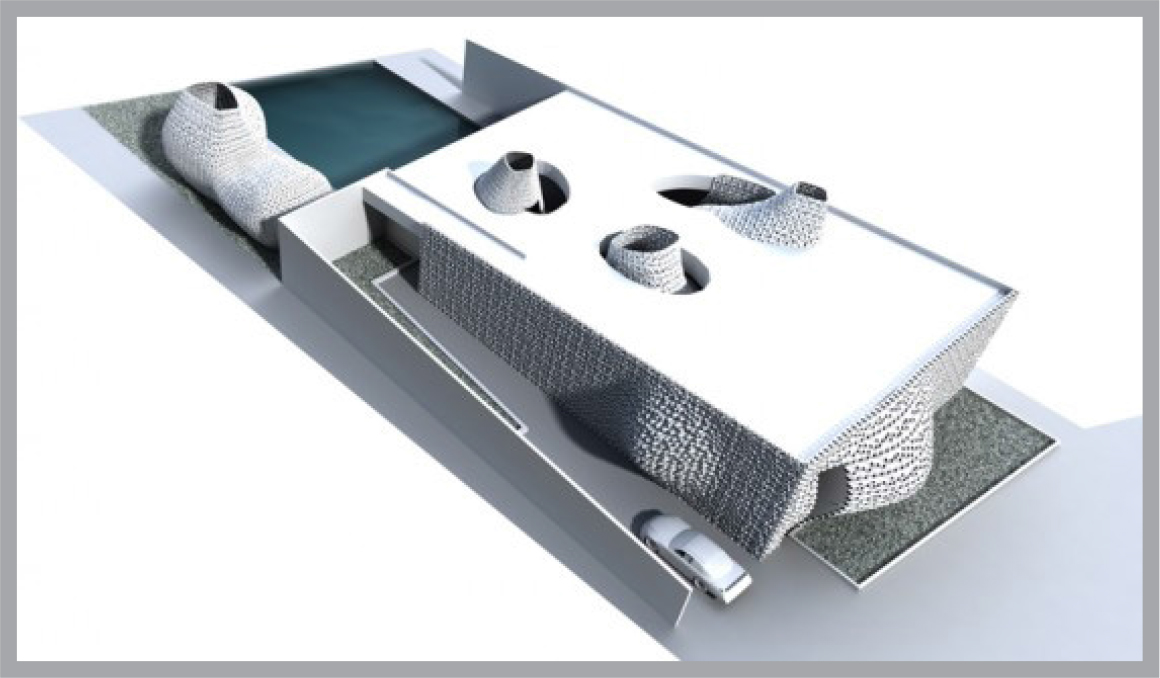

Rael, associate professor of architecture, is one of a small group of researchers advancing a novel type of 3-D printing capable of processing recycled as well as under-utilized materials into a range of sturdy products, from water-cooled walls to full-scale buildings.

In conventional 3-D printing, also known as additive manufacturing, a computer-generated model guides an industrial robot to deposit layer upon layer of extruded material, producing an object of the desired shape. The technology has progressed rapidly, and already is used to create sculptures, jet aircraft parts, and very recently, an apartment building in China.

The process is versatile and precise but usually limited to materials that can be extruded, or pushed through a mold. Typical materials are metals, plastics and cement.

In the 3-D printing process that Rael has been developing, raw materials aren’t extruded. Instead they are in powder form, and sprayed with water layer by layer to help bind the material together. Once the parts are cured, the three dimensional building component can be removed.

3-D printing with powder is actually one of the oldest 3-D printing processes, Rael says. “But we are experimenting with powders made from materials that have never been used before. We are probably the only group looking at powders made from recycled material.”

In the U.S., more than 70 million tons of sawdust fall to the floor each year as lumber is cut to size. Rael has shown that his 3-D printing technology can use sawdust as a starting material. If developed to commercial scale, the process could fabricate building blocks while saving natural resources.

“Construction in the U.S. alone generates almost 15 million tons of debris,” Rael says. “We think we can recycle quite a lot of the debris for use in construction.”

With funding from the Bakar Fellows Program, he plans to advance the technology and show its commercial potential.

“I hope to refine some of the material we have been working on. I’d like to test the materials and push toward making them compliant with building standards. We’d like to demonstrate the construction of a full-scale prototype house using salt and sawdust.”

In his Wurster Hall printFARM (print Facility for Architecture, Research, and Materials) Rael has shown that the powder-water preparation can work with a surprising range of materials.

“It is very robust. We are having success producing novel structures with novel materials — not only sawdust, but pulverized tires, ceramic, sand, and flyash. Some of these would be very difficult to fabricate otherwise.”

Novel materials are only part of his mission. He wants the new technology to add beauty and greater variety to building designs.

“We’re looking for a new construction process perfectly consistent with building codes, but also one that can make the building environment more beautiful. Often, beauty and design and building aren’t considered together.”

His group has built a self-supporting pavilion, which they named Bloom (right). Its 840 customized 3-D-printed blocks are composed of a polymer made from recycled vegetable oil and a cement that uses very little water. The porous structure’s flowing, curtain-like walls show the aesthetic possibilities.

In the printing process, each printed block included a different part of an overall floral design. When assembled, the structure displayed the full floral pattern on both sides of the sinuous wall.

Rael says he hopes this type of 3-D printing can become widely adopted in “sustainable, beautiful and meaningful architecture and construction.”

“I would like to think we are laying the ground work for creating historic structures of the future.”

____________________________

The Bakar Fellows Program supports innovative research by early career faculty at UC Berkeley with a special focus on projects that hold commercial promise. For more information, see http://bakarfellows.berkeley.edu.