Research Bio

Matthew Walker is a professor of neuroscience and psychology in the Department of Psychology and with the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute. Professor Walker is also the founder and director of the Center for Human Sleep Science. He has received numerous funding awards from the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, and is a Kavli Fellow of the National Academy of Sciences. His research examines the impact of sleep on human brain function in healthy and disease populations. To date, he has published over 100 scientific research studies.

Research Expertise and Interest

sleep, neuroscience

In the News

New Research Finds Deep-Sleep Brain Waves Predict Blood Sugar Control

Deep Sleep May Mitigate Alzheimer’s Memory Loss, Berkeley Research Shows

Sleepless and Selfish: Lack of Sleep Makes Us Less Generous

How we sleep today may forecast when Alzheimer’s disease begins

Brain noise contains unique signature of dream sleep

Stressed to the max? Deep sleep can rewire the anxious brain

Disrupted sleep in one’s 50s, 60s raises risk of Alzheimer’s disease

Sleep loss heightens pain sensitivity, dulls brain’s painkilling response

Chronically anxious? Deep sleep may take the edge off

Poor sleep triggers viral loneliness and social rejection

Offbeat brain rhythms during sleep make older adults forget

Everything you need to know about sleep, but are too tired to ask

The Sleep-Deprived Brain Can Mistake Friends for Foes

A new UC Berkeley study shows that sleep deprivation dulls our ability to accurately read facial expressions. This deficit can have serious consequences, such as not noticing that a child is sick or in pain, or that a potential mugger or violent predator is approaching.

Poor sleep linked to toxic buildup of Alzheimer’s protein, memory loss

Sleep may be a missing piece of the Alzheimer’s puzzle. The toxic protein that is the hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease blocks the deepest stages of sleep, resulting in memory decline, according to new research.

‘Sleepless in America’ documentary to feature Berkeley research

We spend one-third of our lives sleeping, and yet it is only in the last decade or so that scientists have begun to really understand why.

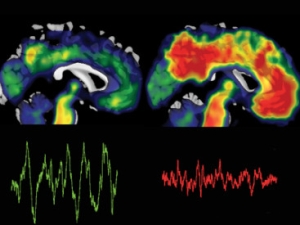

Tired and edgy? Sleep deprivation boosts anticipatory anxiety

UC Berkeley researchers have found that a lack of sleep, which is common in anxiety disorders, may play a key role in ramping up the brain regions that contribute to excessive worrying.

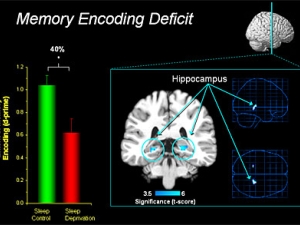

Poor sleep in old age prevents the brain from storing memories

The connection between poor sleep, memory loss and brain deterioration as we grow older has been elusive. But for the first time, scientists at the University of California, Berkeley, have found a link between these hallmark maladies of old age. Their discovery opens the door to boosting the quality of sleep in elderly people to improve memory.

Sleep loss leads to anxiety, poor food choices

Two new studies by researchers at UC Berkeley’s Sleep and Neuroimaging Laboratory unveil further evidence about the dangers of too little sleep.

Dream sleep takes sting out of painful memories

They say time heals all wounds, and new research from UC Berkeley indicates that time spent in dream sleep can help. UC Berkeley researchers have found that during the dream phase of sleep, also known as REM sleep, our stress chemistry shuts down and the brain processes emotional experiences and takes the painful edge off difficult memories.

Not enough sleep gets in the way of success

Pulling an all-nighter can bring on euphoria and risky behavior

A sleepless night can make us cranky and moody. But a lesser known side effect of sleep deprivation is short-term euphoria, which can potentially lead to poor judgment and addictive behavior, according to new research from UC Berkeley.

As we sleep, speedy brain waves boost our ability to learn

Scientists have long puzzled over the many hours we spend in light, dreamless slumber. But a new study from UC Berkeley suggests we’re busy recharging our brain’s learning capacity during this traditionally undervalued phase of sleep, which can take up half the night.

An afternoon nap markedly boosts the brain's learning capacity

If you see a student dozing in the library or a co-worker catching 40 winks in her cubicle, don’t roll your eyes. New research from UC Berkeley shows that an hour’s nap can dramatically boost and restore your brainpower. Indeed, the findings suggest that a biphasic sleep schedule not only refreshes the mind, but can make you smarter.

Featured in the Media

People's sleep patterns can predict Alzheimer's pathology in their brains later in life, finds a new study led by psychology and neuroscience professor Matthew Walker. Using data from the longitudinal Berkeley Aging Cohort Study, the researchers found that people whose sleep quality declined during their 50s and 60s tended to have more protein tangles in their brains, raising their risk for Alzheimer's. "This finding may suggest that decreasing sleep duration in mid to late life is significantly associated with an increased risk of late-life Aβ burden, and that a profile of maintained (or even subtle increase) in sleep duration throughout this time period is statistically associated with a reduced predicted risk of Aβ accumulation in late life," the researchers wrote in their report. "If validated in larger longitudinal studies, these sleep-sensitive windows would have the potential to be included in public health recommendations with the goal shifting from a model of late-stage Alzheimer's disease treatment to earlier-life Alzheimer's disease prevention," they added. For more on this, see our press release at Berkeley News. Stories on this topic appeared in dozens of sources, including Medicine News Line, Daily Mail (UK), and News Live TV.