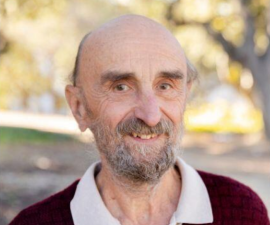

Research Bio

Hans-Rudolf Wenk received his Ph.D in crystallography at the University of Zurich in 1965 and joined the UC Berkeley faculty in 1967. He has many research collaborations, for example with scientists at the Geophysical Laboratory in Washington DC, with Los Alamos National Laboratory and the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, as well as international institutions such as the Universities of Trento/Italy and Metz/France and the GeoForschungsZentrum in Potsdam/Germany.

His current research focuses on understanding anisotropy and the development of preferred orientation in a variety of materials ranging from deformed rocks to metals and bones. Most recently his focus has been on seismic anisotropy and stresses in surficial sediments, tectonically deformed rocks in the crust as well as minerals in the mantle and inner core. Investigations make use of neutron diffraction, synchrotron x-rays and electron microscopy. These experiments can be conducted at temperature-pressure-stress conditions close to those in the deep earth.

Research Expertise and Interest

crystallography, earth & planetary science, structural geology & rock deformation, seismic anisotropy

In the News

Beaches near Hiroshima littered with glassy beads from atomic bomb blast

High pressure experiments reproduce mineral structures 1,800 miles deep

UC Berkeley and Yale University scientists have recreated the tremendous pressures and high temperatures deep in the Earth to resolve a long-standing puzzle: why some seismic waves travel faster than others through the boundary between the solid mantle and fluid outer core.