Beaches near Hiroshima littered with glassy beads from atomic bomb blast

Beaches around the Japanese city of Hiroshima are littered with minuscule glassy beads formed from debris melted by the atomic bomb blast that devastated the city nearly 75 years ago, according to a new study by Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley scientists.

The beads, which no one seems to have noticed until now, apparently formed in the atomic cloud from melted or vaporized concrete, marble, stainless steel and rubber, among other materials of daily life in Hiroshima. The researchers estimate that a square kilometer (0.4 square mile) of beach sand collected from a depth of about 4 inches would contain about 2,200 to 3,100 tons of the particles.

“This was the worst man-made event ever, by far,” said Mario Wannier, a retired Berkeley Lab geologist who led the study. “In the surprise of finding these particles, the big question for me was, you have a city, and a minute later you have no city … Where is the city? Where is the material? It is a trove to have discovered these particles. It is an incredible story.”

The fission bomb dropped by an American bomber on Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, instantly killed more than 70,000 people, while an equal number died afterward from radiation effects. The bomb and resulting firestorms mostly leveled an area measuring more than 4 square miles and destroyed or damaged an estimated 90% of the structures in the city. A second bomb was dropped on the city of Nagasaki three days later, bringing a tragic end to World War II.

Wannier first noticed the irregularly shaped glass beads in 2015, while combing through beach sand collected by colleague Marc de Urreiztieta from Japan’s Motoujina Peninsula, about four miles from Hiroshima. Wannier studies sand around the world to monitor the health of local marine environments.

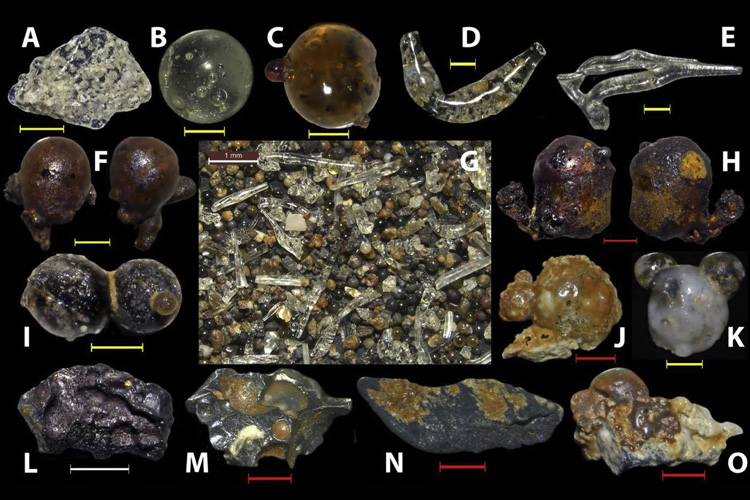

He thought the unusual particles, measuring ½ to 1 millimeter across, resembled glassy beads resulting from meteor impacts, such as the one that killed off the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. So, he teamed up with UC Berkeley mineralogist Rudy Wenk to analyze the beads using electron microscopy and X-ray microdiffraction at Berkeley’s Lab’s Advanced Light Source.

Wenk found a wide variety of chemical compositions in the samples, including aluminum, silicon and calcium; microscopic globules of chromium-rich iron; and microscopic branching of crystalline structures. Other beads were composed mostly of carbon and oxygen.

“Some of these look similar to what we have from meteorite impacts, but the composition is quite different,” said Wenk, a professor of the graduate school in Berkeley’s Department of Earth and Planetary Science and a Berkeley Lab affiliate. “There were quite unusual shapes. There was some pure iron and steel. Some of these had the composition of building materials.”

The experiments and related analyses determined that the particles had formed in extreme conditions, with temperatures exceeding 3,300 degrees Fahrenheit (1,800 Celsius). The composition and formation led the researchers to conclude that they were formed in the bomb blast.

“It was quite fascinating to look at all of these materials,” Wenk said, noting that the beads may be radioactive. “What we hope is to get other people interested in looking at this in more detail and in looking for examples around the Nagasaki A-bomb site.”

Wannier, de Urreiztieta, Wenk and their colleagues reported the findings earlier this year in the journal Anthropocene.