Research Bio

Daniel Rokhsar is a professor of Genetics, Genomics, and Development in the Department of Molecular & Cell Biology. His research is focused on understanding the origin, evolution, and diversity of animals (and, more generally, other groups of eukaryotes) by combining computational genome analysis with comparative developmental biology.

Current Projects

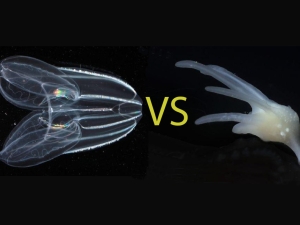

Comparative analysis of genomic diversity across animals and their relatives. The first signs of animal life appear in the fossil record ~600 million years ago. Modern survivors of these early progenitors include sponges, placozoans, cnidarians (anemones, jellyfish, hydra), ctenophores (comb jellies), and bilaterally symmetric animals (flies, snails, worms, humans). Each of these modern phyla retains some of the genomic dowry inherited from the early animals, elaborated on (and sometimes overwritten by) subsequent evolutionary innovations (and losses). By comparing genomes, we not only characterize the basic biochemical, physiological, and developmental tool kits of animals, but also map out their evolutionary history, and infer evolutionary mechanisms for the emergence of animal diversity complexity from more humble unicellular beginnings. Surprisingly, we are finding evidence for deep conservation of exon-intron gene structure, gene content and even chromosomal linkages and are using these features to try to reconstruct aspects of ancestral animal genomes.

Evolution of nervous systems and animal behavior. The nervous system is a characteristic feature of eumetazoans (animals other than sponges), and presumably arose early in animal evolution from pre-existing pathways for regulated secretion and control of membrane potential. Although living cnidarians are often considered to have a simple nerve net with neurons but no complex patterns of neural connectivity, analysis of the sea anemone genome reveals a relatively complex neural genome with highly elaborated gene sets for neurotransmitter metabolism, regulated secretion, control of membrane potential, and other hallmarks of neurons in higher organisms. These genes are expressed in non-trivial patterns, suggesting that the apparently featureless nerve net of sea anemones has cryptic complexity. Even more remarkably, the apparently neuron-less placozoan Trichoplax has most of the genetic machinery to make neurons, but no recognizable neuronal cell type based on morphology. Through analysis of these systems and available genomes, we expect to uncover the core neural gene sets and networks that underlie the diversity of neural organizations in eumetazoa.

Molecular analysis of spiralian development and evolution. Molluscs and annelids represent two diverse animal phyla that are united (along with several other groups of unsegmented worms) within the superphylum Spiralia, sharing spiral cleavage patterns early in development that give rise to a primitively free-living larval form, the trochophore. This ancient and widespread developmental pattern has been conserved at least since the early Cambrian -- over 540 million years and we can infer that animals resembling the modern trochopore in structure and development existed in these ancient seas. We are developing the owl limpet as a genome-enabled model system for the molecular study of spiralian development. This genome serves as a platform for the study of more far-flung molluscan groups, including the octopus and squid, which evolved neural complexity independently of vertebrates.

Research Expertise and Interest

genetics and genomics, evolution of animals, genetic diversity in animals and plants

In the News

What Did the Earliest Animals Look Like?

Reconstructing the Chromosomes of the Earliest Animals on Earth

Chan Zuckerberg Biohub Awards $21 Million to 21 Berkeley Researchers

Study helps map path to improved cassava production

A new analysis of the genetic diversity of cassava will help improve strategies for breeding disease resistance and climate tolerance into the root crop, a staple and major source of calories for a billion people worldwide.

What do leeches, limpets and worms have in common?

Leeches, despite the yuck factor, have captured the hearts of two University of California, Berkeley, scientists who are part of a team that this week is publishing the leech’s complete genome sequence.

Genome of ancient sponge reveals origins of first animals, cancer

A team led by Daniel Rokhsar has published a draft genome sequence of the sea sponge, an organism that wasn't recognizied as an animal until the 19th century. The genome gives insight into the origins of multicellular animals and cancer.

Scientists report first genome sequence of frog

The African clawed frog, Xenopus, has helped scientists understand how embryos develop and the many chemical reactions going on inside dividing cells. Now, scientists report the first draft genome sequence of Xenopus, setting the stage for a more complete genetic analysis of this popular frog.