Research Bio

Dacher Keltner is a professor in the Department of Psychology. Throughout his career he has been interested in two animating questions. How do emotions shape human social life? And what is the nature of human hierarchies, as manifest in power, class dynamics, and how inequality shapes the human psyche?

The Science of Emotion

He has been a central voice in making the case that emotions serve important social functions, enabling us to fold into relationships vital to survival, like friendships, groups, romantic partnerships, and parent-child attachments. Guided by this framework, he has studied emotions like embarrassment, shame, love, compassion, amusement, and gratitude.

Beginning with his post-doctoral fellowship with Paul Ekman, he has long studied emotional expression from a Basic Emotion perspective. He has done work documenting the universality of upwards of 20 distinct facial expressions, the richness with which people can communicate emotion in the voice, and how people communicate emotions like love, compassion, and gratitude through touch.

His work in the field of emotion has moved into new territory during the past few years. First, continuing his collaboration with former student Alan Cowen, they have made several pioneering contributions in the study of emotion with data driven approaches. With new Machine Learning approaches, they have documented universal expressions of emotion in the face and voice, they have charted the meaning of emotional expression in pre-Colombian art, and they have offered the richest characterization to date of the emotional meaning of music, all papers published in top journals. These latter papers have stirred an interest in his lab in the emotional meaning and function of the arts, a central interest of mine going forward. Hhe has recently authored an overview of this new approach to emotion in a widely read theoretical venue.

In his research on emotion, he has continued with force to map the forms and functions of awe, including recent work on children, some of the first of its kind. Building upon this basic science, and grounded in a recent review of the health benefits of awe, they have moved into the realm of awe interventions, publishing results on the benefits of awe for the elderly who take “awe walks” he designed, and for health care providers during the COVID epidemic. He summarized this work in a recent book published by Penguin Press, AWE: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How it Can Transform Your Life. More recently he has authored invited theoretical articles on emotional expression, awe, positive emotions, and the bidirectional relationship between emotions and culture.

Power and Social Class

In 2003 he published a theory of how power influences social life, that is known as the Approach/Inhibition Theory of Power. This theory presents an integrative account of the effects of power on human behavior, suggesting that the acquisition of power has a disinhibiting effect regarding the social consequences of exercising it.

Building upon that theorizing, with collaborators Paul Piff and Michael Kraus, he has offered a theoretical account of how social class shapes human thought, feeling, and action. In empirical demonstrations of this work, they have shown that people from more privileged class backgrounds are more likely to drive through pedestrian crosswalks and cheat on tests to win a prize, feel less compassion than those who suffer, and explain their success in terms of their own superior traits.

More recently, they have explored other issues related to hierarchical life. With Maria Monroy, they have published recent work on intersectionality – the interacting influences of race, class, and gender – on emotion recognition, a theme that he has also explored in studies of implicit bias. He has published work on how economic inequality degrades ordinary social interactions. And building upon his decades of study of social power, summarized in a theory piece from this period of review, he has also published a new account of two strategies to acquire power, coercive and collaborative.

Research Expertise and Interest

culture, conflict, behavior, love, psychology, emotion, social interaction, individual differences in emotion, negotiation, embarrassment, desire, juvenile delinquency, laughter, anger, social perception, negotiating morality

In the News

Dacher Keltner Receives Prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award

UC Berkeley Professor Breaks Down the Science of ‘Inside Out 2’

Berkeley Talks: The Science Behind the Emotions in ‘Inside Out 2’

Dacher Keltner is Awe-Inspired, and You Should Be Too

The 16 facial expressions most common to emotional situations worldwide

UC Berkeley launches new center for psychedelic science and education

Calm amid COVID-19: Gratitude

Nine faculty elected to American Academy of Arts and Sciences

COVID-19: Mental health and well being for ourselves and our children

Calm amid COVID-19: Compassion

Gasp! First audio map of oohs, aahs and uh-ohs spans 24 emotions

UC Berkeley psychology research inspires art world’s first ’empathy center’

Emoji fans take heart: Scientists pinpoint 27 states of emotion

Add nature, art and religion to life’s best anti-inflammatories

Taking in such spine-tingling wonders as the Grand Canyon, Sistine Chapel ceiling or Schubert’s “Ave Maria” may give a boost to the body’s defense system.

Top psychologists to present research on sleep, awe and more at ‘Big Easy’ conference

Poor sleep can sour relationships. Powerful people are better at shaking off rebuffs. Moms who run the household are less concerned with rising to power in the workplace. And people who gaze at the vastness of nature tend to be less self-centered.

Thnx4.org goes live to both teach and research the power of gratitude

UC Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center is providing an easy way to give thanks and, at the same time, contribute to a national research project on the power of gratitude

Affluent people less likely to reach out to others in times of chaos, study suggests

While chaos drives some to seek comfort in friends and family, others gravitate toward money and material possessions, new UC Berkeley study finds.

Study says highly religious people are less motivated by compassion than are non-believers

“Love thy neighbor” is preached from many a pulpit. But new research from UC Berkeley suggests the devoutly religious are less motivated by compassion when helping a stranger than are atheists, agnostics and less religious people.

Upper class more likely to be scofflaws due to greed, study finds

The upper class has a higher propensity for cheating, driving illegally and endorsing unethical behavior in the workplace , believing that “greed is good,” according to a new UC Berkeley study.

Gossip isn’t all bad — new study finds its social and psychological benefits

A new study from the University of California, Berkeley, suggests rumor-mongering can have positive outcomes such as helping us police bad behavior, prevent exploitation and lower stress.

Lower classes quicker to show compassion in the face of suffering

Emotional differences between the rich and poor, as depicted in such Charles Dickens classics as “A Christmas Carol” and “A Tale of Two Cities,” may have a scientific basis. Researchers at UC Berkeley have found that people in the lower socio-economic classes are more physiologically attuned to suffering, and quicker to express compassion than their more affluent counterparts.

Is a stranger trustworthy? You'll know in 20 seconds

There’s definitely something to be said for first impressions. New research from UC Berkeley suggests it can take just 20 seconds to detect whether a stranger is genetically inclined to being trustworthy, kind or compassionate. See if you can guess which people shown in the video have the empathy gene.

Easily embarrassed? Study finds people will trust you more

If tripping in public or mistaking an overweight woman for a mother-to-be leaves you red-faced, don’t feel bad. A new UC Berkeley study suggests that people who are easily embarrassed are also more trustworthy, and more generous. In short, embarrassment can be a good thing.

UC Berkeley psychologists bring science of happiness to China

As the ranks of China's millionaires continue to grow, the pursuit of wealth in the nation is fast outpacing mental health and wellbeing, according to psychologists at the University of California, Berkeley, who are seeking to correct that imbalance and spread the science of happiness in China.

Featured in the Media

Psychology Professor Dacher Keltner, who consulted on the Pixar film, discusses the science of teenage anxiety.

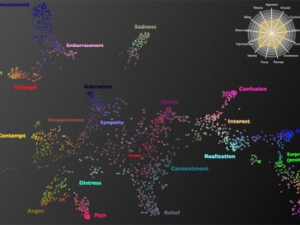

Exploring emotional responses to a wide range of both Western and Eastern music, a team of Berkeley researchers has found "evidence of universality" in the feelings evoked by different musical styles. In a series of experiments led by doctoral neuroscience student Alan Cowen and psychology professor Dacher Keltner, the researchers had more than 2,800 participants from the U.S. and China listen to more than 2,000 samples of instrumental music and then report on how each piece made them feel. Analyzing the data, they identified 13 common emotions, from anxiety, fear, and sadness to eroticism, joy, and serenity. They then transferred the data to an interactive, color-coded map that can be explored online. For more on this, see our press release at Berkeley News. Stories on this topic have appeared in dozens of sources around the world, including Psychology Today, MindBodyGreen, IFL Science, Music Ally, Economic Times (India), Medical Daily, Irish Sun, Study Finds, The Entrepreneur Fund.