Research Bio

Cindy Looy is a paleobotanist and evolutionary biologist whose research focuses on how plants and ecosystems responded to past episodes of environmental change, including mass extinctions. Her work uses fossilized plants, spores, and pollen to reconstruct ancient landscapes and atmospheric conditions.

Looy is best known for her studies on the end-Permian mass extinction—the largest in Earth’s history—and how it radically altered terrestrial vegetation and plant diversity. She also investigates how plant evolution has shaped and been shaped by Earth's climate and atmosphere across geologic time.

An expert in plant evolution, paleoecology, and deep-time environmental change, Looy is a professor in the Department of Integrative Biology at UC Berkeley, Curator of Paleobotany at the UC Museum of Paleontology and Curator of Gymnosperms at the UC Herbarium. She has contributed to international collaborative projects on mass extinctions and is a widely recognized advocate for integrating paleoscience into global change education.

Research Expertise and Interest

paleoecology, paleobotany, palynology

In the News

Pacific Kelp Forests Are Far Older Than We Thought

In Earth’s largest extinction, land die-offs began long before ocean turnover

Women don beards to highlight gender bias in science

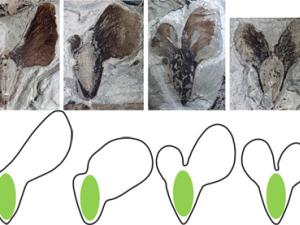

Conifers’ Helicoptering Seeds are Result of Long Evolutionary Experiment

The whirling, winged seeds of today’s conifers are an engineering wonder and, as UC Berkeley, scientists show, a result of about 270 million years of evolution by trees experimenting with the best way to disperse their seeds.

Graduate student brings extinct plants to life

When Berkeley graduate student Jeff Benca submitted a paper describing a new species of long-extinct lycopod, he ditched the standard line drawing and insisted on a detailed color reconstruction of the plant. This piece earned the cover of the American Journal of Botany.

Hindcasting helps scientists improve forecasts for life on Earth

Scientists Core Into Clear Lake to Explore Past Climate Change

One of the oldest lakes in the world, Clear Lake has deep sediments that contain a record of the climate and local plants and animals going back perhaps 500,000 years. UC Berkeley scientists are drilling cores from the lake sediments to explore this history and fine-tune models for predicting the fate of today’s flora and fauna in the face of global warming and pressure from a burgeoning human populations.

Fungi helped destroy forests during mass extinction 250 million years ago

The Permian extinction 250 million years ago was the largest mass extinction on record, and among the losers were conifers that originally blanketed the supercontinent of Pangaea. Now researchers say that climate change led to the proliferation of tree-killing soil fungi that helped destroy the forests – something that could happen as a consequence of global warming today.

Featured in the Media

Kelp was likely available as a food source for ancient marine mammals, said senior author Cindy Looy, a professor of integrative biology.