Federal Appeals Court Sends CRISPR-Cas9 Patent Case Back To Patent Office for Reconsideration

Court of Appeals rules that Patent Trial and Appeal Board applied wrong legal standards

In a decision released today (May 12), the U. S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Washington, D.C., ordered the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) to reconsider its 2022 interference decision that scientists at the Broad Institute in Boston invented CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing in plant, animal and fungal cells.

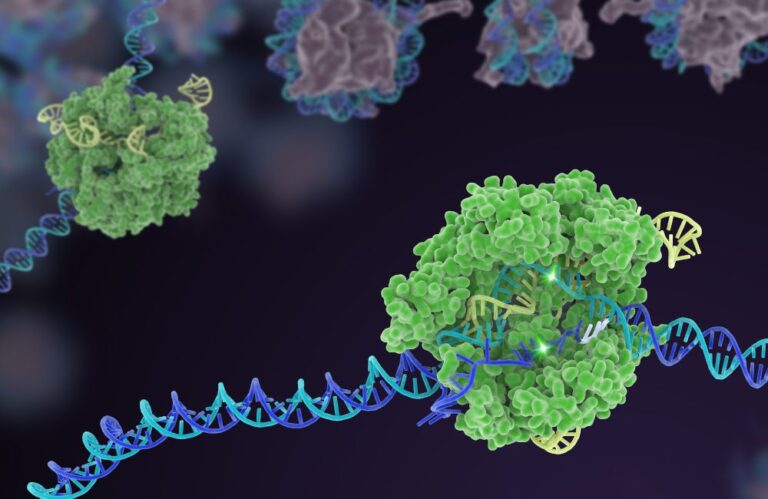

CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing is a revolutionary technique for manipulating DNA invented by Jennifer Doudna of the University of California, Berkeley; Emmanuelle Charpentier, who was then at Umeå University in Sweden; and their colleagues, one of whom was a student at the University of Vienna in Austria. (In legal proceedings, these researchers are referred to as CVC, for California-Vienna-Charpentier). Doudna and Charpentier were recognized for this genome editing breakthrough with the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

“Today’s decision creates an opportunity for the PTAB to reevaluate the evidence under the correct legal standard and confirm what the rest of the world has recognized: that the Doudna and Charpentier team were the first to develop this groundbreaking technology for the world to share,” said attorney Jeff Lamken, who, along with others, represented CVC in the appeal proceedings.

Specifically, the appellate court determined that the PTAB applied the wrong standard and failed to consider relevant evidence in deciding that Broad conceived of the invention before CVC did.

The court concluded that “We vacate the Board’s determination as to conception and remand for further proceedings. On remand, we instruct the Board to reconsider the issue of conception in a manner consistent with this opinion.”

Doudna, Charpentier and their colleagues published their use of CRISPR-Cas9 to edit genes in the journal Science in June 2012. As detailed in that article and in CVC’s first provisional patent application filed on May 25, 2012, the Doudna/Charpentier labs discovered that the tool for cleaving DNA in any cellular environment requires three elements: the enzyme Cas9, which acts like scissors to cut double-stranded DNA; a crRNA that allows Cas9 to home in on a complementary DNA sequence; and a tracrRNA, which pairs with crRNA to create a functional guide RNA for Cas9.

The team made a second breakthrough, demonstrating that the tracrRNA and crRNA could be linked to create a single molecule — a single-guide RNA — that could streamline the gene editing process.

The Broad, a joint institute involving Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, filed its first provisional patent application on Dec. 12, 2012, specifically for the use of CRISPR-Cas9 to edit eukaryotic cells, such as mammal and human cells. The application included experiments confirming that the CRISPR-Cas9 system described by CVC cleaved DNA in eukaryotic cells. At the time these applications were filed, the U.S. had a first-to-invent patent system, though in 2013, it changed to a first inventor-to-file system.

The PTAB subsequently conducted an interference involving 13 Broad patents and one patent application and 14 CVC patent applications to determine who invented the use of CRISPR-Cas9 to edit genes in eukaryotic cells. In 2022, the PTAB incorrectly ruled that the Broad scientists were the first to invent, a decision that CVC appealed to the appellate court.

The appellate court today called the PTAB’s decision on conception an error.

Apart from these contested applications, CVC also owns 57 U.S. patents that were not involved in the interference, nor in the appeal. Those patents claim compositions and methods for the use of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing in all cell types as well as the single guide format of the CRISPR-Cas9 system.

Legal errors

In appealing the PTAB decision to the appellate court, CVC argued three key points: that the PTAB made a legal error in deciding which inventors were the “first to invent” CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing in eukaryotes; it failed to recognize that several labs other than the Broad were able to achieve CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing in eukaryotes with standard lab practices within months after the publication of CVC’s Science article; and that the Broad, in fact, invented nothing new to achieve CRISPR-Cas9 editing in eukaryotes.

CVC noted that the PTAB awarded priority to the fastest “mechanic” to use a new tool instead of the inventors of the novel tool. CVC compared this situation to Alexander Graham Bell’s receipt of a patent for the telephone, even though Bell did not actually build the instrument himself while others did.

Additionally, CVC argued that the PTAB had misapplied the legal standard for determining priority in this case. The PTAB, CVC argued, insisted that the Doudna/Charpentier teams had to know that their proposed methods would work in eukaryotic cells, instead of using the proper standard: That an invention was sufficiently complete when it was ready for skilled artisans to reduce it to practice without further invention. The completeness of the Doudna/Charpentier conception was demonstrated by the fact that five separate research groups, including CVC and the Broad, achieved eukaryotic editing within five months of the publication of the Science article, using standard and routine lab techniques previously used with other gene editing tools.

The appeals court specifically critiqued the PTAB’s ruling that the Broad scientists had invented some sort of new and non-routine technology to use CRISPR-Cas9 in eukaryotes, without any evidence to support such a finding.

The court instructed the PTAB on remand to consider the evidence presented during the interference when applying the correct legal standard to determine who was the first to invent the use of CRISPR-Cas9 in eukaryotes.

CRISPR revolution unimpeded by patent dispute

Despite the slow-moving patent proceedings, worldwide research on CRISPR has proceeded at breakneck speed. The Food and Drug Administration and regulators in the United Kingdom have already approved a gene therapy treatment using CRISPR-Cas9 to treat sickle cell disease.

The University of California has encouraged widespread commercialization of the CRISPR-Cas9 patent family through its exclusive, sublicensable license of the technology to Caribou Biosciences Inc. of Berkeley, California. Independently, Charpentier has licensed the patents to CRISPR Therapeutics AG and ERS Genomics Limited. These licensees have sublicensed the technology to many additional companies in a number of fields.

Consistent with university standards, the UC has preserved the ability for nonprofit institutions, including academic institutions, to use the technology for educational and research purposes.

It was CRISPR Therapeutics, partnering with Vertex Pharmaceuticals, that received the first-ever approval for a CRISPR-based therapy last November, when the United Kingdom granted conditional marketing approval for Casgevy, a CRISPR/Cas9 gene-edited therapy for the treatment of eligible patients with sickle-cell disease and transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia. The U.S. FDA quickly followed suit. The therapy has also been approved in other jurisdictions, including the European Union.

Doudna’s team, through UC Berkeley’s Innovative Genomics Institute, is collaborating with physicians at UCLA and UCSF’s Benioff Children’s Hospital in Oakland on research to discover even better CRISPR therapies for sickle cell disease that would potentially reduce or eliminate the need to destroy patients’ bone marrow cells before reinfusing harvested marrow that has been corrected via CRISPR.