The Andromeda Galaxy Struts Its Stuff

The Hubble Space Telescope completes a high-resolution portrait of our galaxy's gorgeous neighbor.

It may be a “train wreck,” in the words of astronomer Dan Weisz, but it’s a beautiful train wreck.

Weisz, an associate professor of astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley, is referring to the Andromeda galaxy, the nearest large galaxy to our own Milky Way and the closest one that astronomers can study for clues to our galaxy’s evolution.

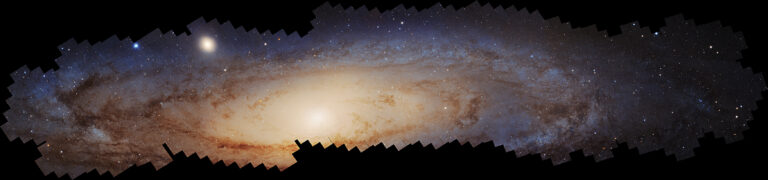

A mosaic image of the entire Andromeda galaxy (Messier 31, or M31), 2.5 million light years away but six times larger than the moon in the night sky, was released today (Jan. 16) by the Space Telescope Science Institute in Maryland. The galaxy’s brilliant yellow center is surrounded by an ethereal blue luminescence, the stars like grains of sand on a beach.

The new image contains 2.5 billion pixels and was produced from about 600 images taken by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope over the past 10 years. Stitched into a single image, the mosaic would cover about 75 8K ultra-high-definition video screens.

What it reveals, Weisz says, is that the galaxy has collided with another galaxy over the past 5 billion years, leaving behind trails of star formation that astronomers can use to trace these collisions into the past. Weisz was a co-principal investigator on the first part of the Andromeda survey, the Panchromatic Hubble Andromeda Treasury (PHAT) program, which produced a hi-resolution image of the galaxy’s northern half in 2015. He is a co-investigator on the second and final phase, the Panchromatic Hubble Andromeda Southern Treasury (PHAST). The mosaic of the combined images was unveiled at the annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society in National Harbor, Maryland.

“It’s the most detailed view of a galaxy outside the Milky Way,” Weisz said. “In fact, you could argue it’s more detailed than the Milky Way, because we can’t even see most of the Milky Way — it’s obscured from our view on Earth. We’re resolving 250 million stars in M31 — it’s incredible. There’s no other galaxy for which we’re able to do that.”

“With Hubble we can get enormous detail about what’s happening on a holistic scale across the entire disk of the galaxy,” said Ben Williams of the University of Washington. Williams is the lead researcher for the PHAST program.

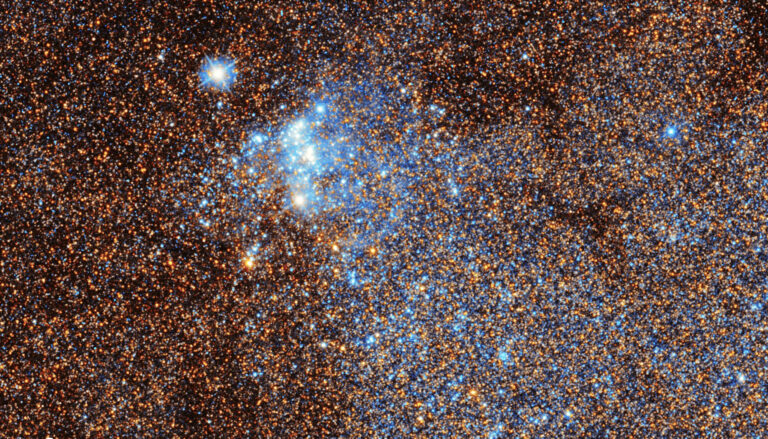

The individual images were obtained at near-ultraviolet, visible and near-infrared wavelengths using Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys and the Wide Field Camera. Only stars slightly brighter than our sun could be resolved by the Hubble cameras — about 0.02% of all the stars in Andromeda.

Of star clusters and satellite galaxies

The earlier mosaic of the northern half of Andromeda revealed a lot about star formation in the galaxy and how it compares to that within the Milky Way. Focusing on Andromeda’s star clusters — groups of stars that formed together from the same cloud of neutral hydrogen gas with a sprinkling of dust and heavier elements — Weisz led a large team that found in 2015 that the distribution of stars within the clusters was amazingly uniform. The proportion of stars of different sizes, ranging from the heaviest blue supergiants to the smallest red dwarf stars, was remarkably consistent across the galaxy and similar to the so-called initial mass function (IMF) in star clusters in the Milky Way.

“It’s hard to imagine that the IMF is so uniform across our neighboring galaxy, given the complex physics of star formation,” Weisz said at the time.

This is important because most stars, including our sun, are thought to form in star clusters before they disperse throughout the galaxy.

“We think most stars form in clusters and then sort of evaporate from the cluster to make up the field, that is, most of the stars that you see,” he said. “By studying star clusters, you are sort of tracking that process by which the star clusters populate the whole galaxy. Our sun probably formed in a cluster that was much closer to the center of the galaxy and has been kicked out to larger distances.”

The newly released image and stellar data on about 100 million new stars approximately doubles the number of star clusters for Weisz and others to analyze, which will help determine how star clusters differ in different portions of the galaxy.

Weisz is also interested in the small satellite galaxies that orbit around Andromeda, and how those differ from the Milky Way’s satellites. Most of these are dwarf galaxies of fewer than a billion stars.

“Given that we know Andromeda is sort of a train wreck, and it’s different than the Milky Way, we want to understand what the impact on the satellite galaxies was because they’re very sensitive tracers of galaxy evolution,” he said. “Little perturbations to the big galaxies make a huge difference for the little galaxies.”

Andromeda past and future

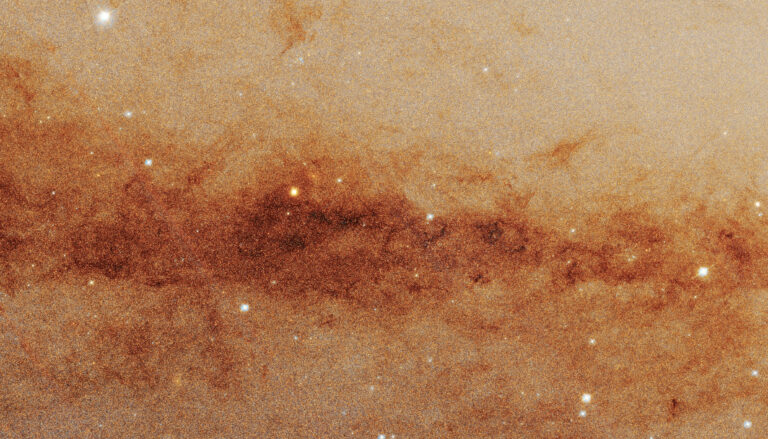

Though Andromeda and the Milky Way likely formed around the same time, the much larger Andromeda — with about a trillion stars versus the Milky Way’s 300 billion — has evolved differently. It has younger stars and unusual features, like coherent streams of stars, which imply that it had a more active recent star-formation and interaction history than the Milky Way.

“It looks like it has been through some kind of event that caused it to form a lot of stars and then just shut down,” Weisz said. “This was probably due to a collision with another galaxy in the neighborhood. We see spikes of star formation around 2 to 4 billion years ago, and the number of stars at that age would suggest that that’s about the time that Andromeda had its main collision.”

A possible culprit is the compact satellite galaxy M32, which resembles the stripped-down core of a once-spiral galaxy that may have interacted with Andromeda in the past. Computer simulations suggest that when a close encounter with another galaxy uses up all the available interstellar gas, star formation subsides.

“Andromeda looks like a transitional type of galaxy that’s between a star-forming spiral and a sort of elliptical galaxy dominated by aging red stars,” said Weisz. “We can tell it’s got this big central bulge of older stars and a star-forming disk that’s not as active as you might expect, given the galaxy’s mass.”

The Milky Way, on the other hand, hasn’t had a collision with another galaxy in about 8 to 10 billion years, he said.

The two galaxies have a linked fate, however.

“In 5 billion years, Andromeda will collide with the Milky Way, and we’ll just have eventually one big elliptical galaxy left in the local group,” he said.

RELATED INFORMATION

- Press announcement from the Space Telescope Science Institute

- Dan Weisz’s website

- UC Berkeley will manage $300 million NASA mission to map the UV universe (2024)

- Berkeley astronomers to put new space telescope through its paces (2022)

- Young astronomer honored for research on smallest galaxies in the universe (2019)