NASA-Funded Project Offers New Insights Into Fire Behavior in Space

Testing in microgravity reveals materials can burn at lower-than-expected oxygen levels

In the coming years, NASA plans to launch long-duration missions to the Moon and to Mars, where astronauts will spend weeks, months or even years living in spacecraft. Understanding fire behavior in these environments is important to ensuring crew safety, but flammability testing conducted on Earth does not always give a complete picture of how materials burn in microgravity.

Now, engineers from UC Berkeley and NASA have teamed up to conduct remote, robot-operated flammability testing aboard the International Space Station. By replicating the atmospheric conditions of spacecraft cabins and space habitats, researchers aim to gain deeper insights and devise strategies for mitigating fire hazards in space.

Known as the Material Ignition and Suppression Test (MIST), this NASA-funded research is one of five projects in NASA’s Solid Fuel Ignition and Extinction (SoFIE) investigation series, which aims to test the flammability in space of materials ranging from cotton-based fabrics to plastics. The findings will help designers select safe materials for space suits, spacecraft cabins and space habitats.

MIST researchers will be investigating the flammability of acrylic plastic, specifically, plexiglass. A lighter-weight alternative to glass, this material could someday be used in new spacecraft windows, helping to increase fuel efficiency. Findings from these experiments will also be applicable to other thermoplastics, such as electrical wire insulation, electronic boards and spacecraft cabin paneling.

“Through these experiments, we hope to improve our understanding of early fire growth behavior and validate models for material flammability,” said co-principal investigator Carlos Fernandez-Pello, Professor of the Graduate School, Department of Mechanical Engineering. “This will help NASA select safer materials for future space facilities and determine the best methods for extinguishing fires in spacecraft.”

During their first round of experiments, the researchers discovered something new. They knew that materials could be more flammable in microgravity, but they were surprised to learn that materials are combustible at oxygen concentrations well below those in normal gravity.

“In normal gravity, the limit of the oxygen concentration at which materials are flammable is approximately 18%. We are finding that in the Space Station, in the spacecraft environment, it’s about 15%,” said Fernandez-Pello. “We were expecting that it would be lower, but not that low.”

He added, “This is an important finding, particularly since NASA is planning to have future spacecraft cabin atmospheres, Exploration Atmospheres [EA], with elevated oxygen concentrations and reduced pressure to facilitate Extravehicular Activity [EVA].”

For Michael Gollner, co-principal investigator and associate professor of mechanical engineering, this finding offers new insight into potential fire risks in space. “Whether the change in this limit is due to air flow velocity or gravity, it means that materials can burn in space that aren’t able to burn on Earth, or that they can sustain a flame for a longer period,” he said. “This is a huge safety hazard and a factor to consider when developing strategies to extinguish these fires.”

During their tests, researchers varied parameters like sample size, oxygen concentration and pressure. In the next round of testing, slated for early 2025, they also plan to study the effects of external radiation on flammability and will install heaters in the Space Station experiment apparatus.

“Adding external heating is always done on Earth to test material flammability safety for buildings, cars or materials. But that kind of testing hasn’t been done in microgravity,” said Gollner. “The heating may further decrease those limiting oxygen concentrations, which would mean things could be even more flammable in space under external heating.”

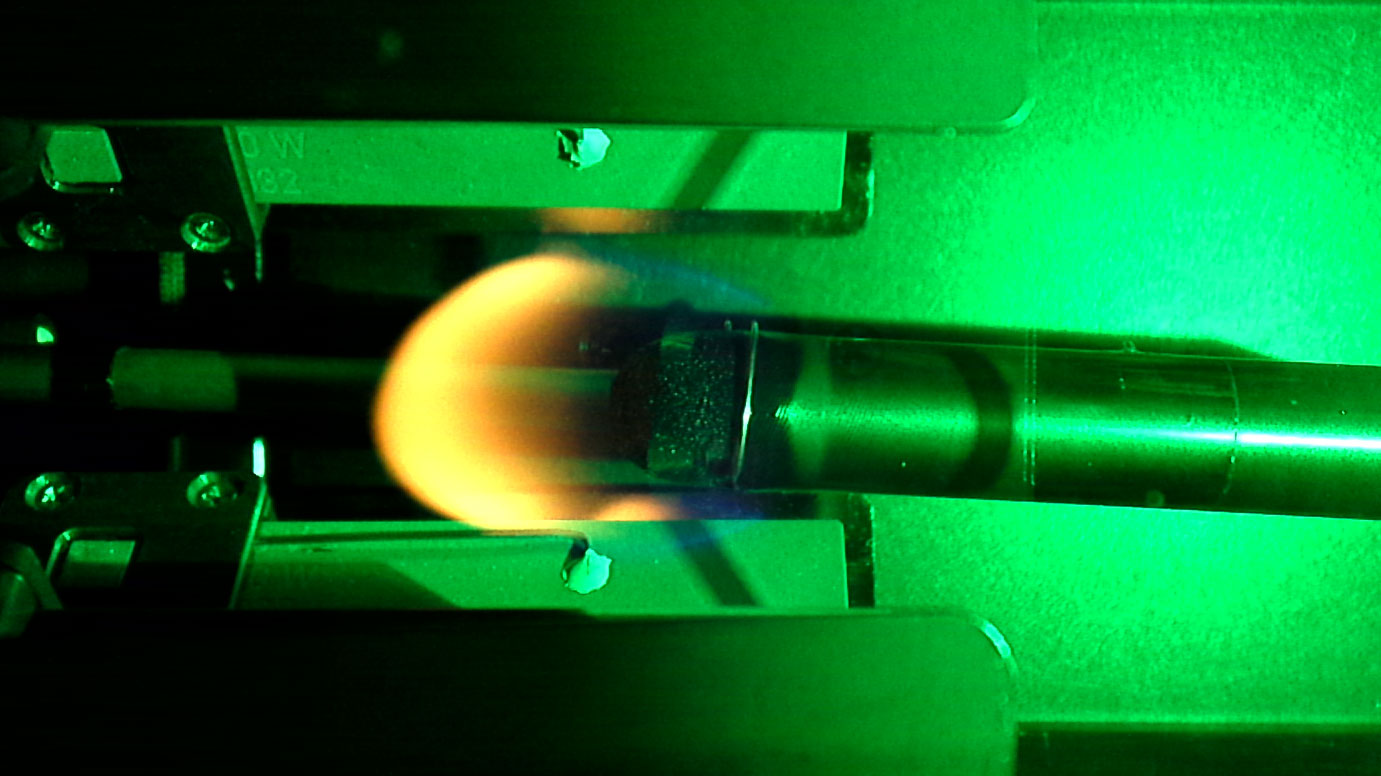

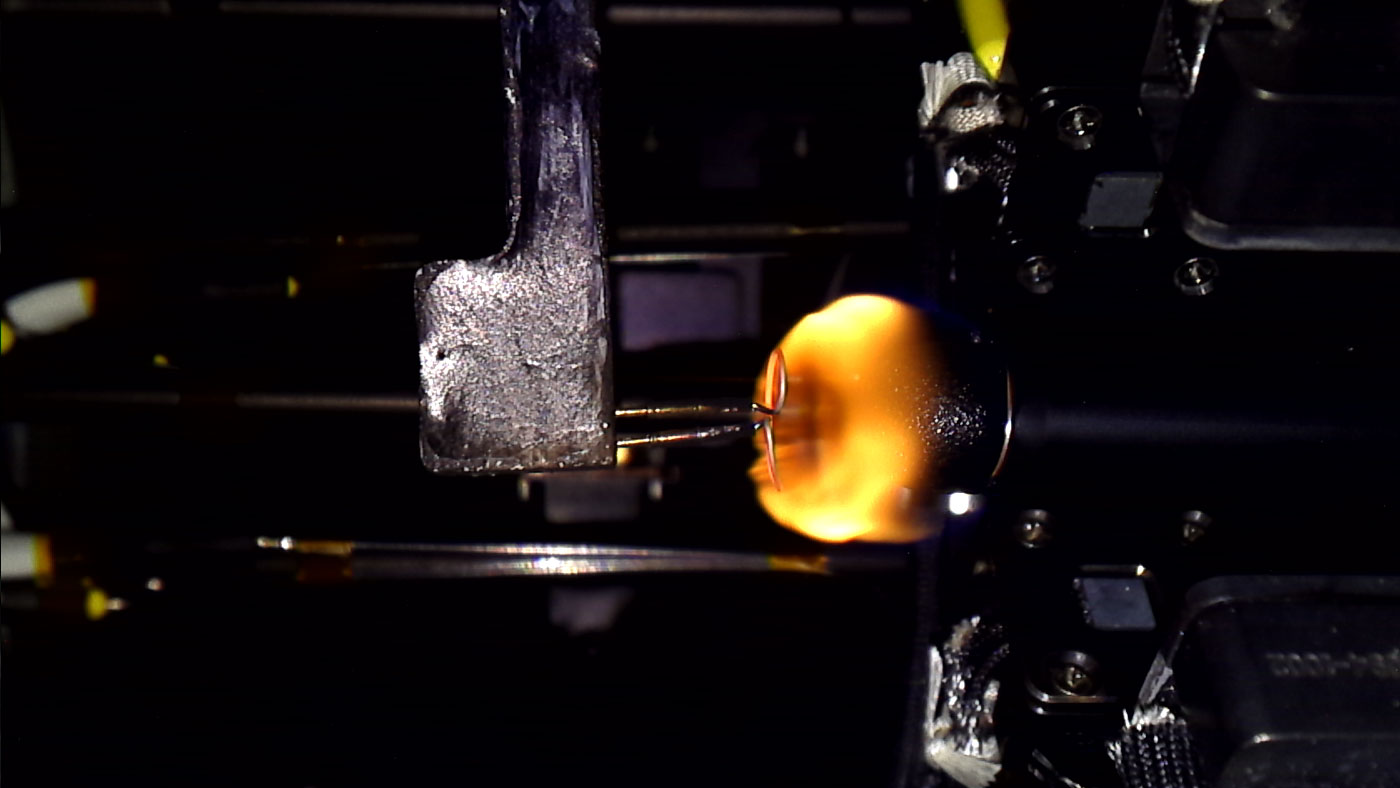

During these experiments, engineers at NASA Glenn Research Center remotely operate the testing apparatus aboard the Space Station. Once ignition is achieved, a small blue flame appears, and the test sample is moved robotically into the test section. If all goes as planned, the Berkeley researchers can watch the entire test on video and interact with the astronauts in real time.

Gollner and the other researchers have been intrigued by their findings as well as the otherworldliness of the flames in microgravity. “They’re beautiful to watch. If you burned a flame in microgravity, it’s going to be blue, like a candle. But since in space you don’t have buoyancy stretching the flame up, it’s just going to grow out, like a blue rounded shape,” he said. “That’s something you don’t see on Earth.”

Expected to conclude in fall 2025, MIST is just the latest project that UC Berkeley and NASA have partnered on, providing a unique experience for both students and professors.

“As a student, working with the NASA researchers has been the most valuable experience of all,” said Jose Rivera, a mechanical engineering Ph.D. student in the Berkeley Fire Research Lab led by Gollner. “Making decisions as a team at Berkeley about ways to modify conditions in the experiment — and then watching the robotic apparatus implement those changes in real time — was really cool.”

For Christina Liveretou, another mechanical engineering Ph.D. student in Gollner’s lab, being able to conduct these tests on the Space Station has helped further her understanding of fire behavior in microgravity, something that cannot be replicated in the team’s lab on Earth.

“From the science perspective, it’s such a unique opportunity to decouple the buoyancy aspect of flammability,” she said. “Conducting experiments in microgravity is our only opportunity to see what combustion truly is when it is not being affected by gravity.”

MIST marks the sixth experiment that Fernandez-Pello has led with NASA. His first was in 1997 with the Kennedy Space Center. Since then, his continued work with the space agency’s microgravity fire program has helped foster a strong, lasting connection between Berkeley engineers and NASA scientists.

“It’s been almost 30 years of Berkeley students participating in these projects, which have become more sophisticated as spacecraft have evolved, as NASA has evolved,” he said. “It has been a tremendous experience to work with astronauts, not only as a researcher but as an academic and a teacher.”

For more information

NASA: Fighting fire with fire: New space station experiments study flames in space