Berkeley startup aims to be a game changer in autoimmune disease therapy

Marco Lobba was five years into his UC Berkeley chemistry Ph.D. program researching the revolutionary CRISPR-Cas9 protein when he found himself in an unfamiliar place: the front of a business school lecture hall.

It was January 2020 — a few months before the coronavirus pandemic began — and the second day of a Haas School of Business entrepreneurship course. Lobba had developed a new way of fusing proteins together that he thought could help treat autoimmune diseases like lupus, multiple sclerosis or Type 1 diabetes.

He just didn’t know how to turn the potentially lifesaving idea into a successful company.

“Good God! I came in with all of these graphs and charts and all this science, and I’m trying to present to a bunch of business majors, whose last chemistry class was likely freshman year of college,” Lobba said. “I wasn’t sure if anyone would see the value behind the science, since it was so far out of scope compared to what other people were working on.”

But in the crowd was second-year MBA student Geo Guillen, a tech product guru hoping a Berkeley business degree would point him to more fulfilling and purposeful work.

“Marco was speaking passionately about his discovery of a new protein conjugation technology. This protein, and that pH level,” said Guillen. “And when he mentioned he wanted to help people, particularly with autoimmune diseases, I was sold immediately.”

At lunch the next day, the outlines of a company were formed. A year later, the pair remotely launched Catena Biosciences with world-renowned Berkeley chemistry professor Matthew Francis.

Today, the company is valued at over $10 million and stands as an example of Berkeley’s change-making spirt: Put entrepreneurial scientists, mission-driven business experts and accomplished faculty in the same space — focused on solving the world’s problems — and innovation will flourish.

“We often find that Berkeley startups like Catena are chasing solutions to big problems versus just chasing checks,” said Rhonda Shrader, head of the Berkeley Haas Entrepreneurship Program. “And that’s really how true innovation comes.”

Lobba pointed to support from campus investment funds and accelerators like the CITRIS Foundry, the SkyDeck Hot Desk program, the Haas Student Seed Fund and the Berkeley Haas Entrepreneurship curriculum.

“Berkeley is great at creating an atmosphere for different departments and colleges to form connections,” he said. “That cross pollination that we have worked on from the very beginning is much of the secret to our success so far.”

‘Accidental discovery’

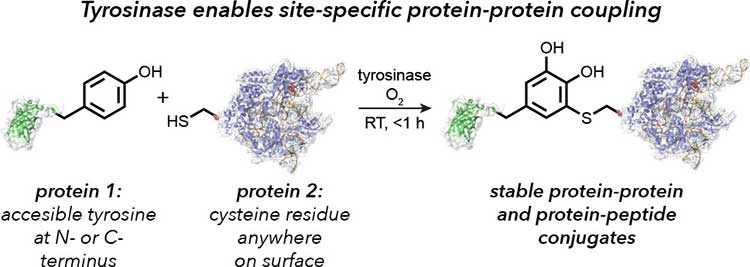

Catena’s technology began at Berkeley in 2004 as basic scientific research. Francis’ lab was studying the modification of proteins when he happened into an accelerated technique —oxidative coupling — to modify proteins using reagents called oxidants to make a faster reaction occur.

Over time, Francis and his team began to notice the reaction could be used to attach proteins together more efficiently.

“A lot of times when you bring full-sized proteins together, reactions start to fail because the proteins interact with each other, they push each other away. And so, you actually can’t form the bonds anymore,” said Francis. “But this reaction goes so fast it has enough power to bring these very large objects together.”

In spring 2017, Lobba and his research partners discovered how using the natural enzyme tyrosinase — found throughout nature and responsible for turning fruits and vegetables, like avocados and apples, brown — could advance that same process to modify very complicated proteins and, in turn, modify cells.

In using naturally occurring amino acids, that process could be used to very reliably fuse any proteins together, faster and more selectively, than any other method being used. That opened the door to treating autoimmune diseases, which attack the body by convincing a person’s antibodies to attack otherwise healthy cells.

Using Catena’s unique protein conjugation technique, scientists can attach safe signals to healthy cells and trick the immune system into no longer attacking them.

“Think of it almost like Pavlov’s dogs, or tricking children into eating their vegetables by covering them in cheese,” said Lobba. “If you present the immune system with something it likes — at the same time as something it is attacking — it starts to associate that target as a good thing.”

That breakthrough is the core technology that Catena Biosciences is built on.

“Our technology is better than the competition because we bypass a lot of the limitations that the industry has in attaching, or combining, proteins together,” said Guillen. “The applications span across multiple spaces from cancer vaccine development and even the creation of enzymatic cleaners or the breakdown of plastics. … It really is a game changer.”

The Berkeley way

But they needed to translate the chemistry into a business, which is why Lobba visited the business classroom that January evening.

Once he was on board, Guillen tried to figure out a business strategy. He conducted a market analysis, held interviews with pharmaceutical companies and sought advice from Berkeley entrepreneurship mentors like Berkeley Haas lecturer Kurt Beyer, who taught Guillen’s entrepreneurship class, and Shrader.

Our product is not publications or patents. It’s people… And that’s really the Berkeley way.”

– Matthew Francis

“We asked ourselves: How can we really make an impact in this world?” said Guillen. “And we identified that the autoimmune market is one that is particularly ripe for disruption because a lot of the approaches to treating autoimmune disease focus on the symptoms, instead of the root cause. It’s a pretty large, untapped market.”

While the startup’s breakthrough can produce powerful immune-training therapeutics across the entire industry — and, in turn, be very lucrative for Catena — Francis said their purpose goes beyond the company’s bottom line.

“I’ll always remember what a mentor said to me on my first day on campus: ‘Our product is not publications or patents. It’s people.’” said Francis, who attended Berkeley as a postdoctoral candidate prior to becoming a faculty member. “And that’s really the Berkeley way.”

Dunking it down

Catena is currently pursuing therapeutic candidates to test their technology and complete preclinical studies by the end of August to track the impact of their therapeutics on autoimmune reactions.

Guillen said the company also aims to be one of the first startups to work at Berkeley’s Bakar BioEnginuity Hub (BBH), which opens this fall. Darren Cooke, executive director of the new Life Science Entrepreneurship Center, is on the tenant selection committee for BBH and has witnessed Catena evolve from an idea to a “budding startup” and said he is not surprised at their rapid success.

“Catena did a great job of navigating the amazing resources we have on campus,” Cooke said. “They really highlight how Berkeley’s entrepreneurship ecosystem enables synergistic collaborations.”

For Lobba, witnessing his peers and other similar startups — such as Scribe Therapeutics and Mammoth Biosciences — sprout from the chemistry and biosciences departments at Berkeley gives him confidence in Catena’s potential.

The company recently won a 2021 Berkeley Big Ideas Award and the founders will pitch their company in September for additional funding. Catena has also been selected to represent Berkeley at the UC systemwide startup demo day in November.

Lobba said his partnership with Guillen and Francis is “a perfect match” and credits the interdisciplinary nature of Berkeley’s academia with bringing them together.

“Matt has been such a stellar chief adviser for us, and I feel like Geo has pitched our company like a layup for me to just come in and dunk it down,” Lobba said.

“Berkeley has this unique ability to tap into the talent of each school on campus,” Guillen added. “We recommend venturing into worlds that take you out of your comfort zone, but also reflect your passion. … At this intersection, incredible things will happen.”