Breakthrough in eliminating dengue, other mosquito-borne diseases

A 27-month trial in Indonesia of a unique method of mosquito control shows that the strategy can reduce the incidence of dengue — a mosquito-borne viral disease of the tropics that threatens nearly half the world’s population — by 77%.

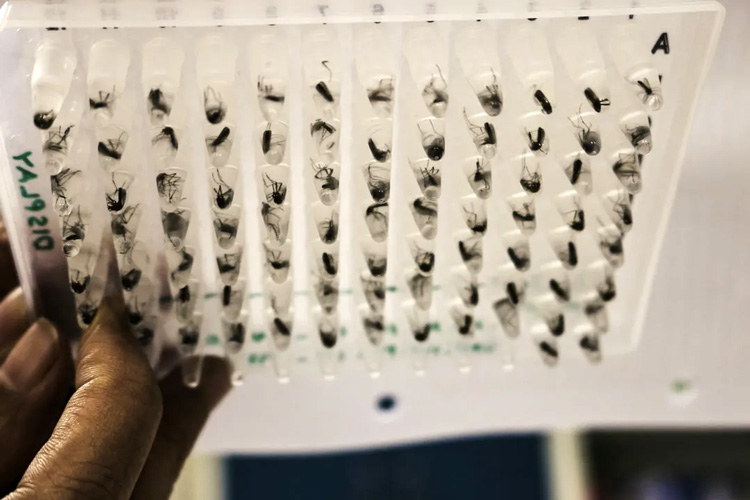

The method, which employs Aedes aegypti mosquitoes infected by bacteria called Wolbachia, effectively prevents dengue-infected mosquitoes from passing on the virus when they bite people. The study, the preliminary results of which were released today (Wednesday, Aug. 26), looked only at dengue, but the mosquito control strategy may likely work for other viruses carried by A. aegypti mosquitoes, including Zika, chikungunya and yellow fever.

“It is a huge breakthrough,” said Nicholas Jewell, a Professor of the Graduate School at the University of California, Berkeley, who designed the study and led the statistical analysis. “We’ve now shown that it works in one city. If this can be replicated and used widely, it could eradicate dengue from several parts of the world for many years.”

More than two years after completion of mosquito releases in the city of Yogyakarta, on the island of Java, Wolbachia remains at a very high level in the local mosquito population, the researchers noted.

“This exciting result of the trial is a great success for the people of Yogyakarta,” said Adi Utarini from the University of Gadjah Mada in Indonesia, co-principal Investigator of the trial. “Indonesia has 7 million dengue cases every year. This trial result shows the significant impact the Wolbachia method can have in reducing dengue in urban populations.”

Dengue is rapidly expanding around the globe — in part, because of global warming — creating a public health challenge and an economic burden. An estimated 50 million cases occur globally every year, yet there currently is no effective vaccine to prevent it, as the one licensed vaccine has limited effectiveness and requires considerable care in administrating it to children. There also is no therapeutic agent to treat dengue and no efficient vector-control strategy to prevent its spread. In 2019, the World Health Organization declared dengue one of the top 10 global health threats because of the absence of effective interventions.

While mild symptoms include fever, lethargy, headache, eye pain, nausea and rash, severe cases can involve severe abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, rapid breathing, signs of bleeding and vascular leakage. Life-threatening complications include dengue shock syndrome and/or severe organ dysfunction.

Dengue and Zika are even making inroads into the U.S. as global warming encourages the A. aegyptimosquito to move northward from the Caribbean, bringing with it the diseases it carries. Florida has had small outbreaks of dengue, while A. aegypti has been found in California’s Central Valley. Once a traveler brings dengue, yellow fever, Zika or chikungunya into the U.S. and is bitten by one of these mosquitoes, the disease can become endemic.

“That is how Zika spread around the world,” Jewell said, referring to recent outbreaks, including the ones in South America in 2015 and 2016, which caused birth defects in the children of many pregnant women who were infected. “People got it after traveling, and then the local mosquito population got Zika, and then other humans got Zika and off you go. That is exactly how mosquito-borne diseases work.”

It’s in just such hotspots in Australia where a Monash University group, the World Mosquito Program(WMP), first piloted its eradication strategy, reporting last year very encouraging results that made news headlines around the world.

The Indonesian study is the first controlled trial of the strategy, in which the WMP partnered with the Tahija Foundation and Gadjah Mada University.

The researchers divided the city of Yogyakarta — about the size of the city of Berkeley, but with nearly four times the population — into a checkerboard of 24 clusters and released Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes into half of them at random. They then worked with all the city’s medical clinics to identify acutely feverish patients and to determine which of the clusters they lived in or had visited within the previous 10 days. All patients were then tested for dengue, something not normally done because the results come back too late to influence treatment.

“It was a complicated study,” Jewell said. “It was not like a vaccine trial, where you could randomly allocate people to getting a vaccine or not. You can’t do that with mosquito-borne diseases. You have to do this over geographical areas and be careful about the drift of the mosquitoes, because we were using a random checkerboard of areas inside this large city.”

The study area included about 312,000 people, and the researchers noted that the Wolbachia deployments were well-accepted by the community, with no safety concerns. In all, 8,144 people, ages 3 to 45, participated after presenting with acute undifferentiated fever lasting between one and four days.

Jewell and doctoral student Suzanne Dufault, who completed her UC Berkeley Ph.D. last spring, received the blinded data in June and analyzed it within a week.

“It was an extraordinary result; to get 77% reduction in dengue incidence is huge, by pharmaceutical intervention standards,” Jewell said. “We will now treat the rest of the city — that was part of the deal, if it worked. I think we then have a chance to eradicate dengue in Yogyakarta.”

This trial is the culmination of a decade of laboratory and field studies that first began in Australia and then expanded to 11 dengue endemic countries.

“This is the result we’ve been waiting for. We have evidence our Wolbachia method is safe, sustainable and reduces incidence of dengue,” said WMP director Scott O’Neill of Monash University. “Now, we can scale this intervention across cities. It gives us great confidence for how we can scale this work worldwide across large urban populations.”

One key benefit of this strategy is that the Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes need to be released only once, and the Wolbachia infect a large proportion of the mosquito population. This does not reduce the mosquito population, as some control measures do, since the mosquitoes essentially breed normally. However, because mosquitoes do not travel far in their brief lifetimes, they must be bred and released at many spots to cover large areas.

Nevertheless, the method is the first efficient intervention for such deadly diseases.

“The basic story is, you get the bacterium into the mosquito, you breed the mosquito, you deploy it, it blocks the virus and bingo,” said Jewell, who also is a professor of biostatistics and epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “It not only blocks one virus, it blocks many flaviviruses. It is like a magic bullet. But would it work? Here, we finally demonstrated it worked in practice.”