Systemic racism hurts not just humans, but urban biodiversity

Racial and socioeconomic inequality is not only harmful to humans, but is also impacting the biodiversity and ecological health of plants and animals in our cities, according to a new review paperpublished online today (Thursday, August 13) in the journal Science.

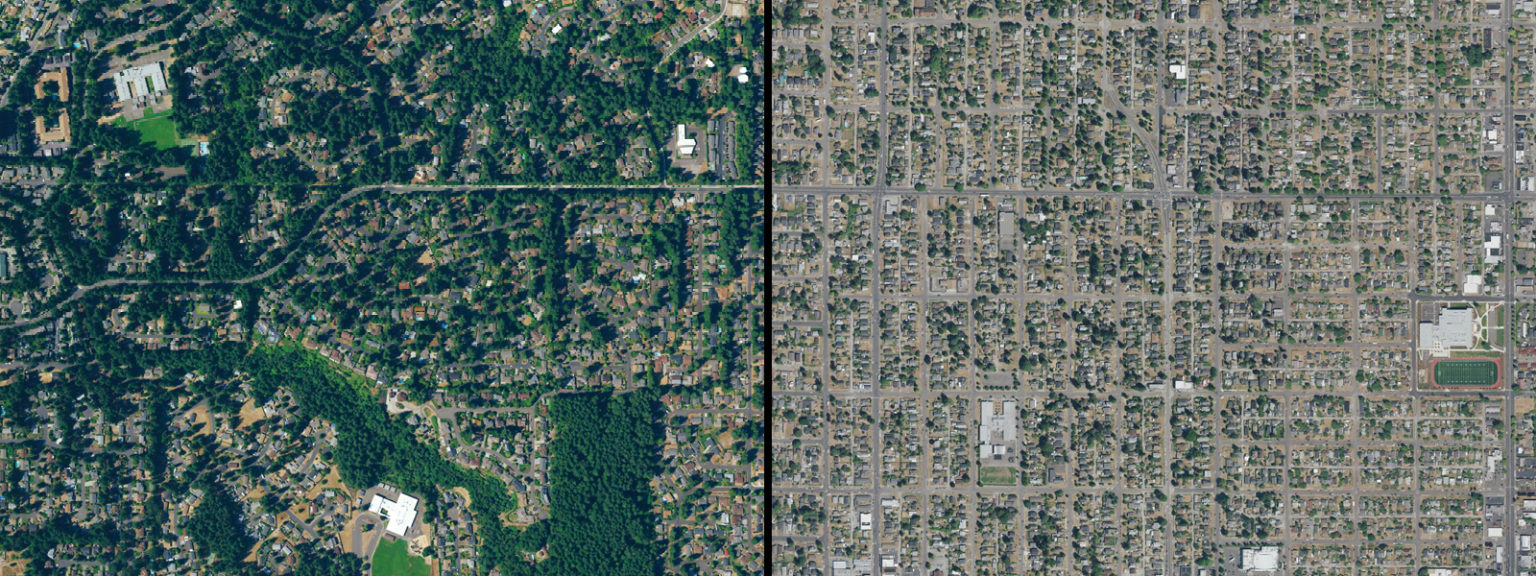

The study authors examined a variety of published studies to explore the influence of systemic inequalities on ecology and evolution. They found evidence that the social and political structures that have driven systemic inequality in this country, such as redlining and Jim Crow laws, have also served to reduce biodiversity, increase the effects of urban heat islands — metropolitan areas that are warmer than outlying rural areas due to human activity — and amplify the impacts of climate crises across the U.S.

“Systemic racism shapes cities in ways that create very different neighborhoods which are hotter, more polluted, have fewer trees and different types of human activity. Scientists trying to understand how biology works in cities will always be missing the mark if they don’t assess the underlying human power structures that make cities look and function the way they do,” said Max Lambert, a postdoctoral researcher at UC Berkeley and senior author of the study. “The reality is that we can’t do urban conservation and hope it leads to better outcomes for people. We have to enact social justice before conservation in cities can ever reach its full potential.”

Most studies of urban ecology focus on wealthier areas, where there is generally better tree cover, more parks and less pollution than lower-income areas, the authors noted. Whether intentional or not, neglecting these areas can obscure vital ecological processes — and a lack of diversity in science may be one of the reasons why the impacts of systemic inequality on biodiversity and evolution have long been overlooked.

“I’ve spent time the past couple of years working on human-created stormwater ponds in cities that are meant to control flooding, deal with pollutants and create habitat. One of the things I’ve noticed and am starting to quantify is that these types of ponds typically aren’t as common — or are often entirely absent — in neighborhoods that have experienced a legacy of racist and classist practices,” Lambert said. “In many ways, it stops me from asking certain questions.”

The team hopes the paper will help the scientific community recognize how many of its practices are based on systems that support white supremacy and perpetuate systemic racism and push scientists to reevaluate how these systems are operating in their own work.

“I hope this paper will shine the light and create a paradigm shift in science,” said lead author Christopher Schell, an assistant professor of urban ecology at the University of Washington Tacoma. “That means fundamentally changing how researchers do their science, which questions they ask and realizing that their usual set of questions might be incomplete.”