Research Bio

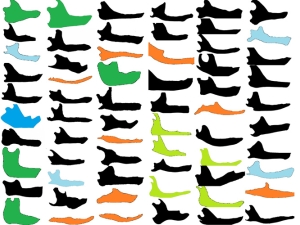

Jack Tseng is an associate professor in Integrative Biology. Research in his laboratory is focused on understanding the macroevolutionary-scale patterns of structure-function relationships in mammals and other vertebrate groups. Projects in his lab include analysis of variables such as dietary and locomotor ecology, evolutionary relationships, and their interplay on the structure and function of the vertebrate skeleton. He uses methodologies such as landmark-based shape analysis (geometric morphometrics), model-based assessments of feeding performance (finite element analysis) as well as experiment-based model validation approaches (mechanical testing and kinematics analysis). He also conducts field-based and collection-based research on extinct mammal groups to understand the influence of inter-continental dispersals on the evolution of predator lineages. His fieldwork areas including Wyoming (Eocene), Inner Mongolia (Neogene), Tibetan Plateau (Neogene), Mexico (Neogene), and southern China (Paleocene).

Research Expertise and Interest

paleontology, jaws, bite force, macroevolutionary trends and patterns, mammals, vertebrates, evolution, vertebrate evolutionary morphology, mammalian systematics, evolution of form and function