Scientists pivot to COVID-19 research, hoping for quick results to deal with pandemic

Thanks to a rapid funding program thrown together by wealthy entrepreneurs barely six weeks ago, seven COVID-19 research projects at the University of California, Berkeley, are getting an infusion of cash — $2.2 million in all — that could turn up new diagnostics and potential treatments for the infection within months.

A diverse group of funders pooled their resources and solicited so-called Fast Grants proposals in early April, promising to evaluate them within 48 hours and send the money within weeks, far faster than any other funding agency, public or private. The contributors wanted ideas for research that would have a quick payoff — results within six months — in order to impact the pandemic now.

Anders Näär, UC Berkeley professor of metabolic biology and vice chair of the Department of Nutritional Sciences and Toxicology, was one of 20 reviewers for what turned out to be a deluge of applications: about 4,000 in all. The grants covered nearly every aspect of the new pandemic disease, from diagnostics to vaccines and treatments.

“I reviewed 350 grants in 36 hours; I slept about four hours during those 36 hours,” he said. “It was quite the challenge.”

So far, Fast Grants, which is part of Emergent Ventures, a project at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, has distributed $22 million to about 100 researchers in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Japan.

Like many researchers who applied, Stephen Brohawn, assistant professor of molecular and cell biology, first heard about the grants on Twitter.

“We had already started work on this project, we had some nice data showing that things look very promising, and we put it together and heard back in two days,” said Brohawn, who was awarded $100,000 to look for drugs that target an ion channel in the membrane of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. He teamed up with Diana Bautista and Hillel Adesnik, professors of molecular and cell biology, who, like Brohawn, study ion channels, something all cells need to function properly.

“There is a possibility that we could come up with a therapeutic that would be helpful in the short term” as we await the development of a vaccine, Brohawn said. “We are going to pursue this as fast as we can.”

Eva Harris, director of UC Berkeley’s Center for Global Public Health and a professor of infectious diseases, received $400,000 toward her goal of raising $2 million for a broad effort to check the infection status of at least 5,000 asymptomatic people across 11 cities in the East Bay through genetic and antibody tests.

“Our research … will provide much-needed insight into transmission dynamics, the true extent of the community spread and risk factors for infection beyond those tested for COVID-19 at hospitals and clinics,” said Lisa Barcellos, professor of epidemiology and biostatistics, who leads the study with Harris.

Patrick Hsu, an assistant professor of bioengineering and member of the Innovative Genomics Institute (IGI), received $300,000 to apply new CRISPR tools he has discovered to a faster and better diagnosis of COVID-19 infection and potentially new therapeutics. The research, conducted in collaboration with Harris, IGI executive director and Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator Jennifer Doudna and David Savage, associate professor of molecular and cell biology, also involves searching for new drug targets using CRISPR genetic screens.

“In normal times, we use CRISPR tools to develop new types of gene and cell therapies for the brain and immune system, and my lab discovered novel CRISPR systems that can target RNA,” he said. “SARS CoV-2 is an RNA virus, so when this pandemic started growing, and California began to shut down, a bunch of us in the lab thought we might be able to harness these RNA-targeting Cas13 enzymes to develop more sensitive diagnostic tests that could potentially be done at home or point of care.”

Searching for drugs to fight COVID-19

Näär did not review his own application, but he was awarded $400,000 to pursue a new idea for treating the viral disease: using antisense oligonucleotides to block replication of the virus, targeting the virus’s RNA genome or, alternatively, RNA in human cells that help make more virus.

Antisense oligonucleotides are basically strings of nucleotides — ribonucleic acids — that attach firmly, like molecular Velcro, to a complementary strand of RNA, making it unreadable. If that target RNA is a key part of the virus’s genetic code, or a piece of human RNA that the virus co-opts to make copies of itself, the virus can no longer reproduce.

He will focus on improved antisense tools called locked nucleic acid antisense oligonucleotides, or LNA ASOs, which he has already developed to treat cardiovascular disease, obesity, Type 2 diabetes and fatty liver disease. His results are so promising that he is looking for funds to move into clinical trials, and he believes LNA ASOs also hold great promise against SARS-CoV-2.

“There is a tremendous amount of interest in health sciences at UC Berkeley, and that is reflected in these COVID-19 efforts,” said Näär. “I was tremendously impressed at the groundswell of support and interest at Berkeley, which is more or less a basic science institution and not one you would necessarily think of as biomedically oriented.”

Two other UC Berkeley research teams also received Fast Grants to search for drugs that inhibit the virus.

Daniel Nomura is leading a group of investigators who plan to use innovative chemical biology approaches to develop novel therapeutics against COVID-19. With $500,000, the team, which includes Niren Murthy, professor of bioengineering, and Jamie Cate, professor of chemistry and of molecular and cell biology, will be looking for weaknesses in the SARS-CoV-2 proteins that could be leveraged by a small molecule, hopefully knocking out the virus.

“We’ve been able to develop very potent inhibitors against the SARS-CoV-2 main cysteine protease (MPro), which is essential for viral replication and which also inhibits the SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV MPros,” he said. “The goal of this project is to develop a drug against not only COVID-19, but also future coronaviruses.”

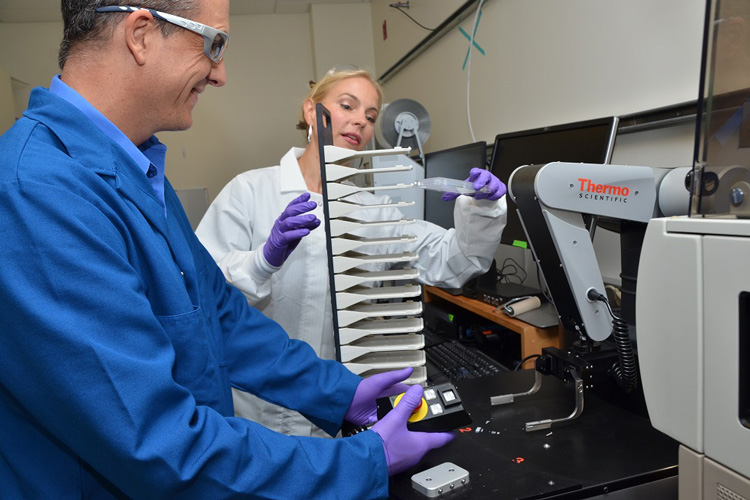

Näär, Brohawn and Nomura will rely heavily on UC Berkeley’s newly opened Drug Discovery Center to take the potential targets they discover and throw drugs at them to see if they knock out the virus.

The center was set up over the past two years by Julia Schaletzky, executive director of UC Berkeley’s Center for Emerging and Neglected Diseases (CEND) and its Immunotherapeutics and Vaccine Research Institute (IVRI), who had just completed startup tests before the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

“It was kind of perfect timing that we had done all this work just before, so now we hit the ground running on screening campaigns and drug discovery campaigns,” she said.

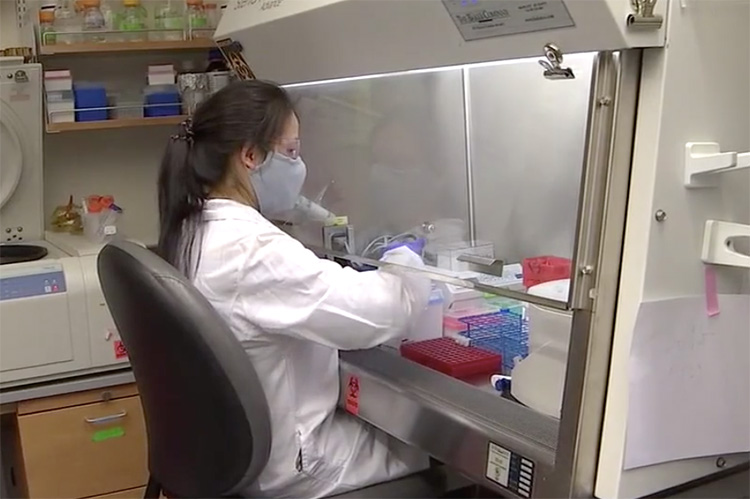

Schaletzky received $300,000 in Fast Grant funding to quickly begin screening more than 1,000 drugs already approved in the U.S. and Europe to see if anything now available for treating an illness will also work against COVID-19. Her collaborator is Sarah Stanley, an associate professor of infectious diseases who normally studies the highly infectious disease tuberculosis. Both TB bacteria and the new coronavirus can only be handled in a Biosafety Level 3 (BSL3) lab, so she was able to pivot quickly to working with SARS-CoV-2.

Stanley will infect human and monkey cells with live SARS-CoV-2, against which Schaletzky will test a library of drugs already approved or undergoing clinical trials. Candidate drugs that rescue infected cells will then be tested in Syrian golden hamsters, one of few animals, other than primates, that are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2. Stanley received $200,000 from Fast Grants to develop the hamster as a model for drug testing and to understand the basic immunology of infection.

Stanley is also raising mice genetically engineered with a human-like immune system in which to test drugs that pass screens.

“I find it super-exciting that so many truly brilliant people are entering the virus field,” said Schaletzky, who organizes the yearly Bay Area Symposium on Viruses. The Fast Grant money is just one pot of new money to support this COVID-19 research (see below).

One notably absent funder, however, is the federal government. While federal agencies have announced that researchers can apply to repurpose existing funds toward COVID-19 research and have promised new emergency funds for projects focused on the pandemic, disbursement has been painfully slow, Schaletzky said. Despite many UC Berkeley proposals submitted to the National Institutes of Health since the pandemic began, for example, none have been granted.

“Why, in a crisis like this, do we have to raise all the money from philanthropy? How bizarre this is,” said Schaletzky, who wrote an op-ed in March about the lack of funding. “We gave $58 billion to the airlines alone, no questions asked. But for research, the money is just not there. I am really glad we have good fundraisers, because otherwise we would just be sitting there waiting.”