Writing slavery back into American business history

When Caitlin Rosenthal worked for McKinsey and Company, a management consulting firm, she regularly thought about issues like turnover, productivity analysis, workforce planning and depreciation. What the management consultant didn’t know is that many of those business practices were honed on slave plantations in the West Indies and the American South.

Rosenthal, today an assistant professor of history at UC Berkeley, has brought that history into fresh focus with her new book, Accounting for Slavery: Masters and Management, which examines how white owners of enslaved black people were early innovators of many business practices and terms we use today.

“It is an attempt to write slavery back into the history of American business,” Rosenthal said of her book.

Business owners in 19th century New England are rightly recognized for developing manufacturing efficiencies like factories and the cotton gin. But Northern business owners had trouble maintaining a stable workforce, losing as much as 100 percent of their employees in a year, Rosenthal said.

Southern plantation owners had no such problem. They owned their workers and were so determined to extract every ounce of the enslaved peoples’ available energy that they ended up developing models of business efficiency still used today.

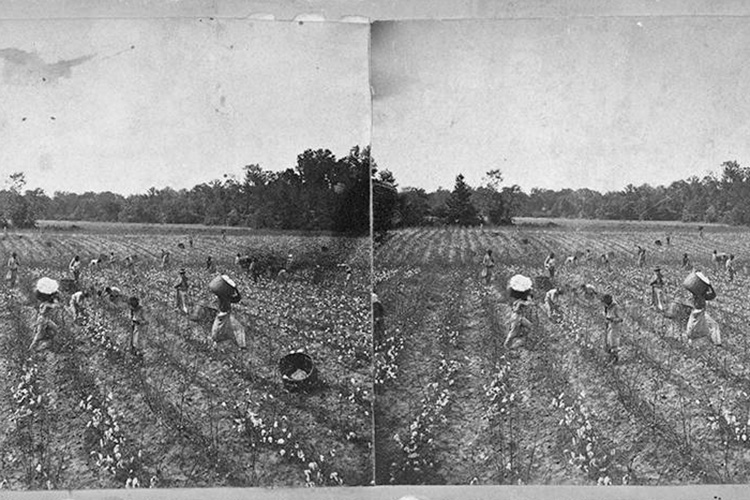

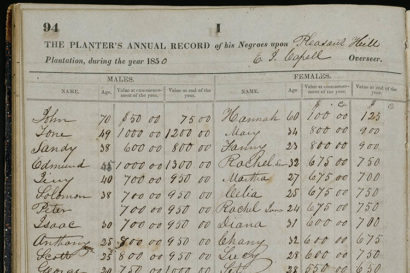

“Planters could lay out the grids of everyone working in their fields, and they could track how much cotton every single person was picking every day,” Rosenthal said. “So, while Northern business owners were struggling to recruit and train new workers, plantation owners were speeding up labor and increasing output per person.”

Rosenthal’s research led to her to Thomas Affleck’s Cotton Plantation Record and Account Book, a workbook of blank standardized business forms published around 1848 and widely available to most plantation owners.

“More advanced than anything I had seen”

The book was “more advanced than anything I had seen in all but the most advanced Northern business books, and here, it was accessible to everyone,” Rosenthal said.

As she reviewed records of plantations, both online and in person, Rosenthal began to find examples of early business innovation that displayed, she said, “more and more moments of sophistication.”

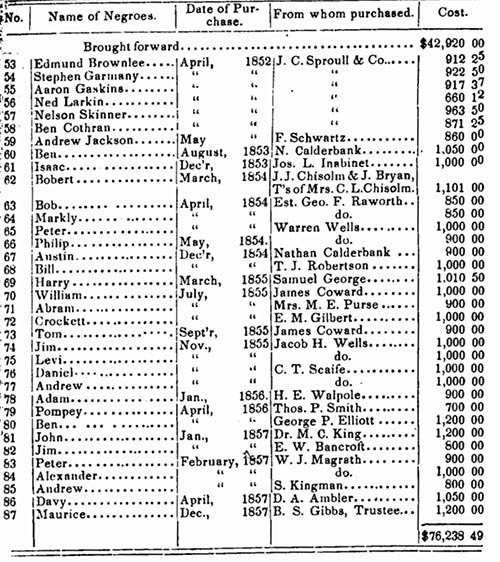

American slaveholders assigned young enslaved people more value as they grew up and depreciated their worth as they passed middle age, a practice usually thought to have been developed by railroad barons.

Enslaved people were graded and sorted as commodities based on their age, health and productivity. The most productive individuals were rewarded with bonuses, while the least productive were punished.

Middle managers ensured that the interests of plantation owners carried over into the fields.

In the British West Indies, enormous plantations were broken up into what today might be described as corporate divisions. The bosses of each division would write standardized quarterly analyses of labor and profit that were sent back to plantation owners in England. Owners would sometimes respond, asking for tweaks in operations to improve profit.

“They had an attentiveness to human capital” — a term known today as human resources management, she said. “Of course, they didn’t call it human capital.”

Lessons for today

All those documents and quarterly reports hold a lesson for today’s business community, Rosenthal said.

“The financial costs are on the page, but the human costs are not,” she said. “It sounds silly to make this very basic point, but especially in Silicon Valley, we need to remember: There are people in the data. It can be very easy to forget that when the data gets bigger and bigger.”

And it is important for business people to recognize the exploitative history of the language and ideas that so many accountants, consultants and MBA students take for granted.

“Very few people imagine that the practices they use have a heritage in a more violent environment,” Rosenthal said. “It is important to understand the way violence and innovation can go together. This is a question of reckoning with slavery.”

“If we’re going to take seriously questions of business ethics, then where better to learn than from these businesses that thought at the time that they were ethical, when we know now that they, of course, were not?” she added.

There’s a lesson, too, in what happens when businesses operate without strict government oversight.

“The broader lesson of the book is what profit-seeking looks like when the rules allow it to absolutely dominate labor,” Rosenthal said. “The planters were enjoying absolutely unregulated capitalism.”

Contact Will Kane at willkane@berkeley.edu.