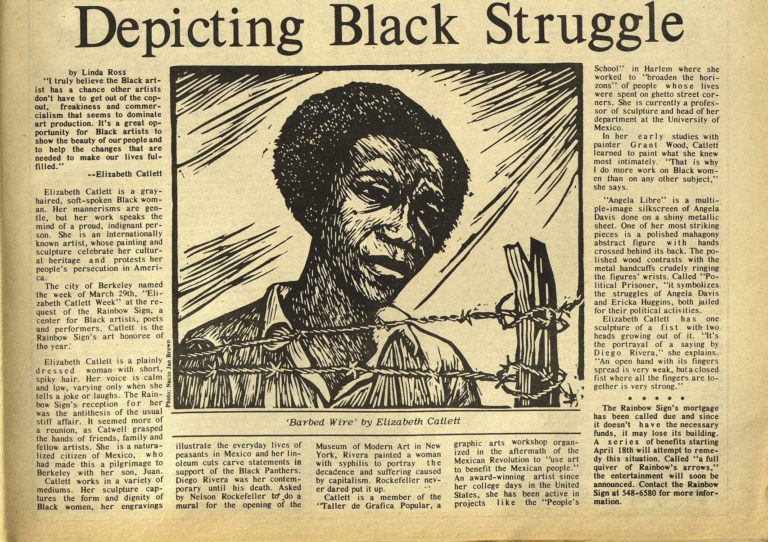

Inside Rainbow Sign, a vibrant hub for black cultural arts

From the outside, Rainbow Sign didn’t look like much. Housed in a modest building — previously a mortuary — it sat on the corner of Grove (now MLK Jr. Way) and Derby in Berkeley, a quiet, beige house with a tasteful, arched doorway.

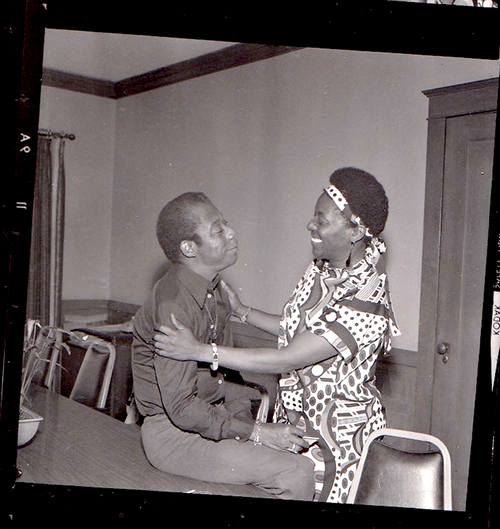

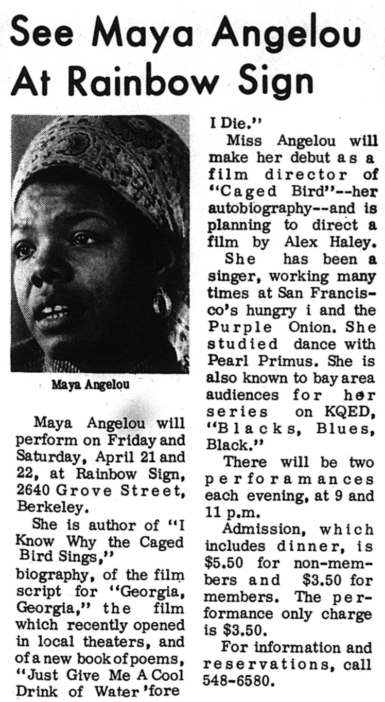

But on the inside was a vibrant black cultural arts center — a 1970s Bay Area hub for black art, music, cinema, literature, education and civic gathering — that drew cultural icons from across the country, from Maya Angelou and James Baldwin to Huey Newton and Nina Simone.

The all-inclusive space — a vision brought to life by founder Mary Ann Pollar — caught the attention of UC Berkeley students Tessa Rissacher and Max Lopez. Together, they decided to go digging through archives to unearth the legacy of the multipurpose venue as part of a digital history project for an undergraduate seminar, taught by professor Scott Saul, on the city of Berkeley’s transformation in the late 1960s and 1970s.

The legacy of the Rainbow Sign lives on in a digital archive, created for the class, along with six other projects, that explore a variety of topics, including the women and girls who lived on Telegraph Avenue, Berkeley’s public schools and desegregation, the Third World Liberation Front at UC Berkeley, a nightclub for experimental music and Berkeley’s thriving trans community in the 1970s.

To get a sense of what the Rainbow Sign meant to the Bay Area community at the time — it was open from 1971 to 1978 — the students pored over hundreds of documents — newspaper clippings, old brochures, membership cards, event posters, photos and contact sheets.

Here’s Rissacher reading from the center’s 16-page brochure:

“Rainbow Sign is a showcase of the best there is of the black experience, a unique, vibrant, never-before-seen element of the culture and heritage we spring from and, in our several ways, are perpetuating,” Rissacher reads. “A place to honor our past, to be aware of our present and to build faith in our future.”

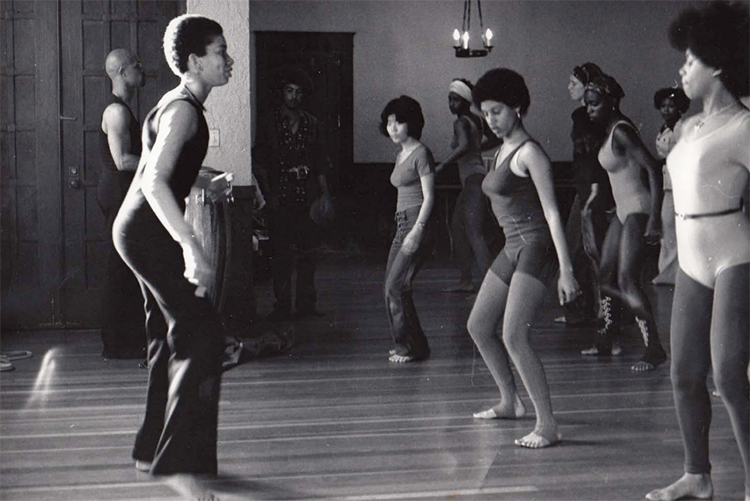

On any given day, visitors at the Rainbow Sign could have a meal at its restaurant, take a dance class, learn Swahili, attend a book party for Black Panther Party leader Huey Newton, make a batik print, listen to Maya Angelou read from her book of new poems or pull an all-nighter at a jazz festival after-party (with a complimentary breakfast served the next morning).

On any given day, visitors at the Rainbow Sign could have a meal at its restaurant, take a dance class, learn Swahili, attend a book party for Black Panther Party leader Huey Newton, make a batik print, listen to Maya Angelou read from her book of new poems or pull an all-nighter at a jazz festival after-party (with a complimentary breakfast served the next morning).

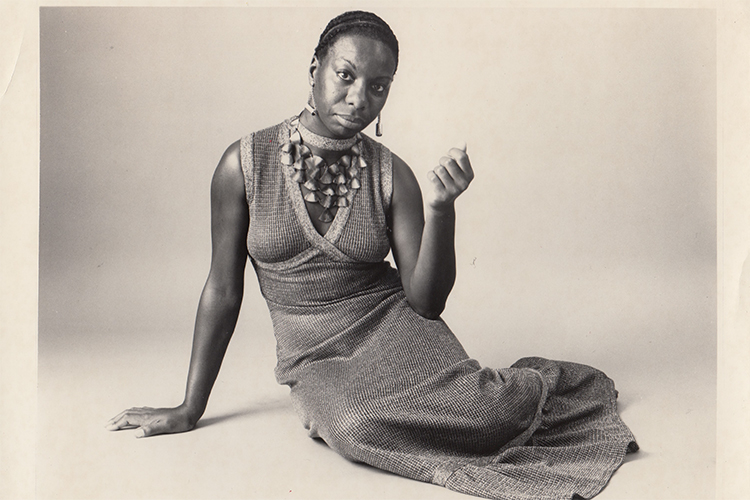

In 1972, a year after Rainbow Sign opened its doors, singer Nina Simone came to town and performed at the intimate venue to a sold-out audience. It was such a big event that Berkeley’s first black mayor, Warren Widener, proclaimed March 31 to be “Nina Simone Day.”

During Simone’s two-day visit to Rainbow Sign, she performed a set of songs, which could have included “To be Young, Gifted and Black,” “O-o-h Child,” and “Jelly Roll,” among others. Here is a photo contact sheet from one of her performances.

It was a place that Rissacher and Lopez say inspired new ways of thinking, something we need more of today.

“Spaces like Rainbow Sign are engines of new creativity,” says Rissacher. “Finding what the new thing is that hasn’t been corporatized and taken over, because you have to be on the vanguard edge of creativity. It’s something that happens together, in community.”

“And providing a space where people can come together is itself generative,” adds Lopez. “Of new culture, new values."

Learning about the Rainbow Sign, and the role it played in promoting black culture in the Bay Area and across the country, has inspired Rissacher, who is pursuing a double major in English and theater and performance studies, to pursue the topic for her thesis.

“This project has kindled a sense of responsibility in me that I haven’t felt in previous work,” says Rissacher. “Rainbow Sign has been so under-studied… There’s so much more there. It was very much a seedbed for all of these different musicians and literary figures and young playwrights and poets and women, especially, who went off to do these amazing things.”

To learn more about the Rainbow Sign, and to view its digital archive, visit the Berkeley Revolution website.