Researchers discover how CRISPR proteins find their target

UC Berkeley researchers have discovered how Cas1-Cas2, the proteins responsible for the ability of the CRISPR immune system in bacteria to adapt to new viral infections, identify the site in the genome where they insert viral DNA so they can recognize it later and mount an attack.

These proteins, which were recently used to encode a movie in the CRISPR regions of bacterial genomes, rely on the unique flexibility of the CRISPR DNA to recognize it as the site where viral DNA should be inserted, ensuring that “memories” of prior viral infections are properly stored.

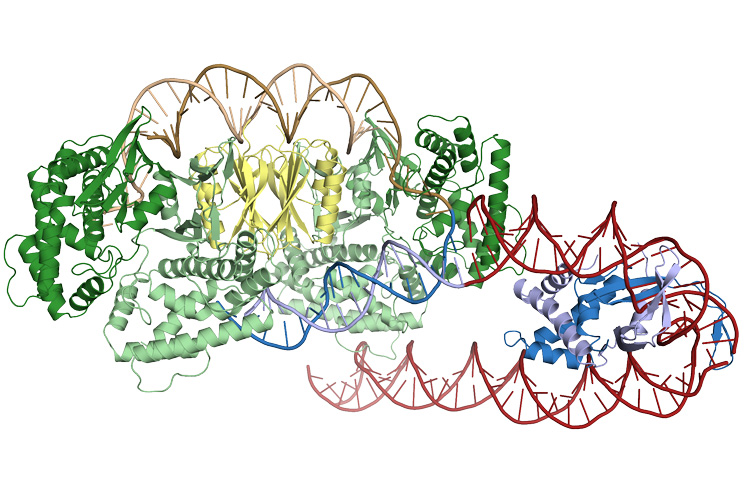

The paper, which will be published online July 20 in Science by Jennifer Doudna and her research group, used electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography, performed at the Advanced Light Source at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, and the HHMI electron microscope facility at UC Berkeley, to capture structures of Cas1-Cas2 in the act of inserting viral DNA into the CRISPR region. Doudna is a professor of molecular and cell biology and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator at UC Berkeley.

The structures reveal that a third protein, IHF, binds near the insertion site and bends the DNA into a U-shape, allowing Cas1-Cas2 to bind both parts of the DNA simultaneously. The lead authors, graduate student Addison Wright and postdoctoral fellow Jun-Jie Liu, along with co-authors Gavin Knott, Kevin Doxzen and Eva Nogales, discovered that the reaction requires that the target DNA bend and partly unwind, something that occurs only at the proper target.

CRISPR systems are a bacterial immune system that allows bacteria to adapt and defend against the viruses that infect them. CRISPR stands for clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats and refers to the unique region of DNA where snippets of viral DNA are stored for future reference, allowing the cell to recognize any virus that tries to re-infect. The viral DNA alternates with the “short palindromic repeats,” which serve as the recognition signal to direct Cas1-Cas2 to add new viral sequences.

Specific recognition of these repeats by Cas1-Cas2 restricts integration of viral DNA to the CRISPR array, allowing it to be used for immunity and avoiding the potentially fatal effects of inserting viral DNA in the wrong place, Wright said.

While many DNA-binding proteins directly “read out” the nucleotides of their recognition sequence, Cas1-Cas2 recognize the CRISPR repeat through more indirect means: its shape and flexibility. In addition to coding for proteins, the nucleotide sequence of a stretch of DNA also determines the molecule’s physical properties, with some sequences acting as flexible hinges and others forming rigid rods. The sequence of the CRISPR repeat allows it to bend and flex in just the right way to be bound by Cas1-Cas2, allowing the proteins to recognize their target by shape.

Research published last week by geneticist George Church and his colleagues at Harvard University showed that the information-storing capabilities of Cas1-Cas2 can be repurposed for recording frames of a movie instead of viral sequences and could possibly be used for recording other sorts of information as well.

The discovery of how Cas1 and Cas2 recognize their target opens the door for modification of the proteins themselves. By tweaking the proteins, researchers might be able to redirect them to sequences other than the CRISPR repeat and expand their application into organisms without their own CRISPR locus.