Minimum wage hikes don’t eliminate jobs, study finds

Increasing the minimum wage does not lead to the short- or long-term loss of low-paying jobs, according to a new study co-authored by University of California, Berkeley, economics professor Michael Reich and published in the November issue of the journal The Review of Economics and Statistics.

The study resolves the often conflicting research on the minimum wage in the United States and may provide guidance in future policy debates on the topic, said Reich, who is also the director of UC Berkeley's Institute for Research on Labor and Employment.

While the study focused on restaurant workers, he and his research colleagues reported evidence that their findings apply to workers in other low-wage industries as well.

"This is one of the best and most convincing minimum wage papers in recent years," said Lawrence Katz, an economics professor at Harvard University and a specialist in labor economics.

Much economic policy discussion today is more focused on a general lack of jobs rather than on inadequate pay, said Reich, but that doesn't negate the need for adequate or "living'" wages.

Although increasing the minimum wage can stimulate the economy by putting more money in the pockets of those most likely to spend it on necessities, he said, suggestions to raise minimum wages typically trigger fears. These fears center around the idea that raising the minimum wage would force many employers to reduce job offerings to meet a more expensive payroll, or that a "tipping point" where the minimum wage becomes too high has already been reached.

Reich noted that the federal minimum wage was first adopted as part of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, in the midst of the devastating Great Depression. More than 87 years later, the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour provides a full-time worker an annual salary of approximately $14,500 a year. Over 32 states plus the District of Columbia have had minimum wages higher than the federal level. Washington state's is the highest at $8.55 per hour, and San Francisco has a citywide minimum wage that is about to increase to $9.92 per hour.

"It seems likely that we will have a number of state minimum wage campaigns next year, with more in 2012," Reich said. "Bill Clinton was able to get a Republican House of Representatives to pass a federal increase in 1996 – that could happen again."

Reich's co-authors included Arindrajit Dube, an assistant economics professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and a research associate at Amherst's Political Economy Research Institute, and T. William Lester of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, an assistant professor at UC Berkeley's City and Regional Planning specializing in economic development. They said their findings indicate that an entire generation of previous minimum wage studies that found negative effects on jobs is fundamentally flawed.

The two sets of minimum wage studies cited most often in debates about raising the minimum wage reach different conclusions. One group of researchers relied on local case studies and the other on national level data and state variation over time.

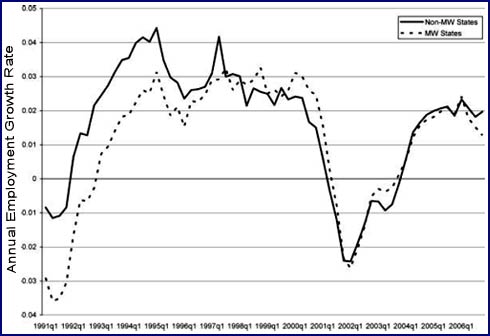

The main problems, said the authors of the new study, are that the case study research could not be generalized to other areas and covered very short time periods, while the other research approach failed to account for critical differences in employment growth between minimum wage and non-minimum wage states that are unrelated to the minimum wage.

"Our reading of the literature suggests that this difference in methods may account for much of the difference in results," the researchers wrote.

For example, they said in the article, both minimum wages and overall employment growth vary substantially over time and location, as seen in the South, where the economy has been growing faster than it has in the rest of the country for reasons unrelated to the South's lack of state-based minimum wages.

The article noted that 17 states and the District of Columbia had a minimum wage higher than the federal level in 2005 and consistently lower job growth than the rest of the country from 1991 to 1996. However, those 17 states and states on the other end of the minimum wage spectrum experienced almost identical job growth between 1996 and 2006.

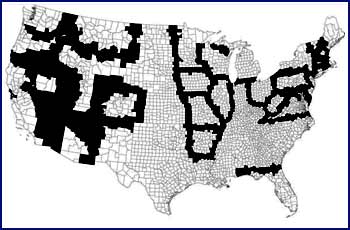

For their paper, "Minimum Wage Effects Across State Borders: Estimates Using Contiguous Counties," Reich, Dube and Lester built upon the earlier studies, pulling together local and national level data covering 16 years.

They crunched data from across the country on county pairs that straddle state borders and have a minimum wage differential, examining differences between the pairs in terms of the number of jobs and pay for workers in restaurants, retail, accommodation and food services.

The researchers used data supplied by the Quarterly Census of Employment for 66 quarters from 1990 to 2006. They merged this data with information on the local, state and federal minimum wage in effect during each quarter.

About 33 percent of restaurant workers across the country are paid no more than 10 percent above the minimum wage. Restaurant and retail workers together account for almost half of all employees in the United States who are paid within 10 percent of the federal or state minimum wage.

The new study is available online.