Why Did Medieval Readers Kiss, Smudge and Deface Their Books?

“What they were really touching was each other,” says French Professor Henry Ravenhall. “The book was just a conduit for whatever kind of social desire was needed to be expressed within that group.”

As a specialist in medieval French literature, Henry Ravenhall has examined hundreds of manuscripts from the Middle Ages. Every time he does, he sits quietly in a special library viewing room and gingerly turns each page with clean, dry hands, careful not to tear or otherwise harm these precious artifacts.

“When you look closely at the surface itself, you see patterns of how paint has been smudged or certain characters defaced,” said Ravenhall, an assistant professor in the Department of French at UC Berkeley who’s at work on a book provisionally titled Touch and the Experience of Medieval French Manuscripts. “These signs tell us that medieval culture worked in a way that was totally different from the way we’re thinking about these objects.”

But in his research, Ravenhall has found that medieval readers didn’t treat these books with the same light touch that we do today.

Examine a medieval text, and you’ll see images of certain characters with their faces erased of all detail or entire scenes that are cloudy from repeated touch. It may seem like such imperfections were accrued over centuries of wear and tear, but often these defacements came directly from medieval readers, who touched, smudged and kissed the texts as they read them.

For medieval readers, the experience of reading was about more than sitting alone quietly with a book, Ravenhall says; physically interacting with manuscripts provided a way for readers to connect with each other and express themselves in ways they perhaps couldn’t in their daily lives. His research has shed new light on the social nature of reading in the Middle Ages, and how our reading habits today could be more similar to those of medieval readers than it first appears.

UC Berkeley News talked with Ravenhall about who was reading these medieval manuscripts, why they were defacing them and how this research “radically shattered” how he thinks about reading today.

UC Berkeley News: In your current book project, you’re looking at the illuminations, or illustrations, of five specific French medieval texts and how readers interacted with them in the past. What have you found?

A lot of what reading meant in the Middle Ages was also looking at and touching images. Throughout the texts, there are patterns of interaction — certain characters are defaced more than others, and then certain gestures are involved, so certain directions of the hand, you know, things like faces are always targeted, hands are often touched, feet are sometimes touched. So there’s a kind of set of practices that are circulating alongside the transmission of manuscripts.

And that’s not to say that these objects, these beautifully illustrated books, were not valuable — they were — but it’s in spite of that value, or maybe because of it, that they’re touching them. It’s totally different from how we think of these objects as precious artifacts, antiques. And that raised all kinds of questions about what is reading, if reading involves this kind of destructive touch.

One of the texts includes The Romance of the Rose, a copy of which is held at the Bancroft Library. How did you decide which books to include in your research?

I chose books that have a lot of copies. I’m looking at the same text to see if the same images or the same scenes, the same passages, have attracted the same kind of interactions.

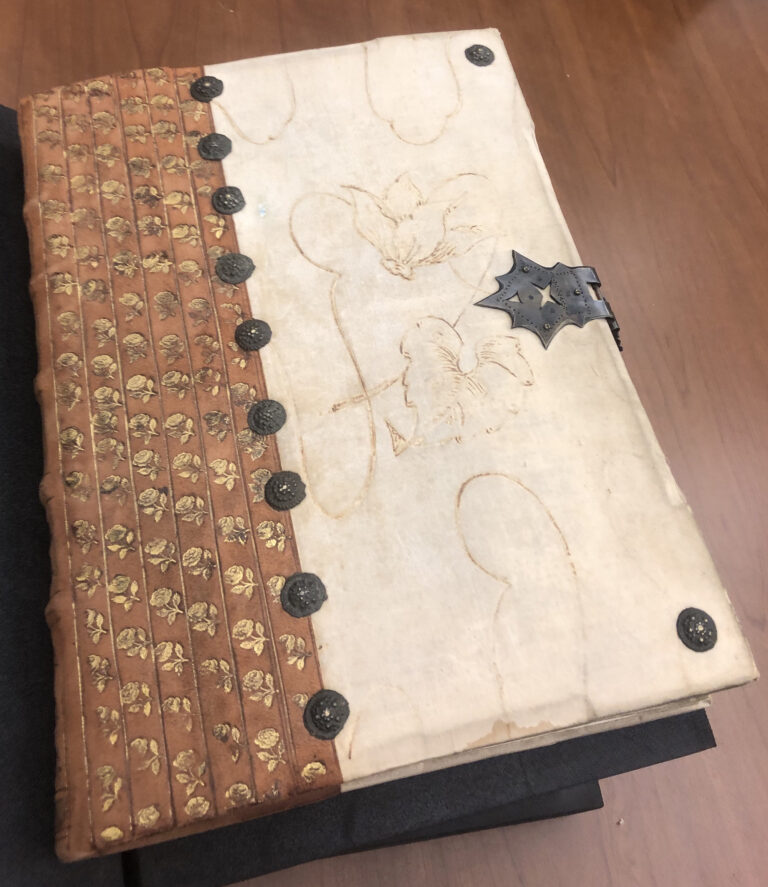

The Romance of the Rose is a medieval French bestseller. There are more than 300 copies in different libraries around the world today, so that means there was a huge, huge number in circulation back then. It’s a bizarre text — it’s a love poem, a dream vision, but then also becomes a kind of encyclopedia of all medieval culture. The copy in the Bancroft, the binding is made of this scented wood, and you can smell this fragrance, even though it’s over 500 years old. I can’t even imagine how strongly it must have smelled back then. (See a copy of the book in the Bancroft Library’s digital collections.)

Who were the medieval readers interacting with these texts?

Most of the manuscripts that we have were meant for aristocratic or wealthy bourgeois audiences, because owning a book was incredibly expensive, especially with illuminations. Medieval readers, aside from kings and dukes, would have quite a small collection of books that they would read over and over again. Lower-class audiences would experience literature in more local, oral settings in public performances, especially epic songs in marketplaces. So that’s how the non-literate, non-book owning classes would engage with literature.

For the aristocrats who had books, were they all literate? If not, how did they read?

Up until about 1200, most texts in Western Europe were written in Latin, and to be literate, in a sense, was to know Latin. The people who were trained in Latin were mostly churchmen. So they learned Latin to be able to access important texts, and to teach and transmit the word of God.

Then over the 12th and 13th centuries, vernacular languages became more prevalent. We know that some aristocrats could read and were trained in literacy, and others weren’t. By the end of the 13th century, a lot of people had a kind of partial literacy. In particular households and courts, there would be clerics who were trained to read and write.

There was a wide variety of possible reading situations. They could involve someone, like a cleric or churchman, reading a book out loud and, at the same time, passing it around a small group. When you think about those kinds of alternative modes of reading, you see that reading can involve precise social dynamics.

Suddenly, reading seems incredibly strange from the way we think about reading today, as one person with one book kind of phenomenon. We’ve lost that kind of sociability. Even if people were touching the manuscript, what they were really touching was each other. The book was just a conduit for whatever kind of social desire is needed to be expressed within that group.

What were these stories about, and what was the motivation behind touching, smudging, kissing and otherwise defacing the images?

A lot of reading in the Middle Ages was concerned with ethics, like how to live properly. That’s partly to do with a culture of more diffuse religiosity. When you’re in a culture where everything is geared to a final judgment, where all your acts are weighed at the end of time, you’re going to be concerned with ethics and how to live a good life. And literary texts are good at presenting conundrums. I think one of the reasons that people like literary texts is that they provide some kind of dilemma that is meant to be thought over. When you’re reading ethically, it’s a different type of reading.

When we think about defacement as a gesture that expresses some kind of ethical judgment — this person is good or this person is bad — it is a way of consolidating that response. Especially since the illuminations tend to represent the evil or the problematic act. That’s where, often, you might see a defacement. And their interpretation is a way of asserting a value or performing one’s belief as a certain ethic.

I think we don’t really have that today. We have a different relationship to ethics and literature. We think about ethics as being divorced from literature, except for in children’s literature, where it’s more kind of thickly framed.

Is there a particular text you’ve been studying that especially speaks to the morals and ethics of the Middle Ages? What do its defaced illuminations tell us about how readers felt about the story?

I’m writing something at the moment about one of most canonical texts of medieval French literature — Yvain, the Knight of the Lion by Chrétien de Troyes. The story starts with a knight, Yvain, avenging his cousin, who was defeated in a duel and humiliated. He kills the man who defeated his cousin, and in the end, Yvain, who has undergone a kind of transformational arc, falls in love with and marries the man’s widow.

The ending is short and ambiguous, and is debated by feminist scholars. You can read it as a happy ending, but if you think about it from the female character’s point of view, you realize she has no agency in this decision, and she’s basically forced to spend the rest of her life with the person who killed her husband.

At the end of one of the manuscripts, this figure, the female character, is really seriously defaced. You can read that as a kind of enjoyment at the end, that it’s a happy ending, or you can read it as a way of processing what is essentially a violent, deeply ambivalent ending for the character. These reactions remind us that medieval interpretations were messy and unpredictable and varied, just as they are today.

In what ways are medieval readers and the way they interacted with texts different or similar to the way we read today?

When trying to think of modern analogies, I think a lot about the late 1990s, early 2000s magazine culture. Magazines have an incredibly tactile surface — there’s a certain pleasure just in handling the objects. As a kid, I remember touching bits of the images, touching the text. And at the time I was doing it, I couldn’t tell you why. But that was part of my reading process, a part of understanding.

The other comparison I often think about is the various gestures we use to consume modern media. We pinch, we zoom, we scroll. We’re surrounded by text and language everywhere, all the time. Reading has taken on this very specialized meaning of, you know, sitting down with a book, whereas in the Middle Ages, it is just a kind of engagement with text and image. But that’s what we’re doing on our phones; we just don’t think of it as reading.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.