When parole, probation officers choose empathy, returns to jail decline

Heavy caseloads, job stress and biases can strain relations between parole and probation officers and their clients, upping offenders’ likelihood of landing back behind bars.

On a more hopeful note, a new UC Berkeley study suggests that nonjudgmental empathy training helps court-appointed supervision officers feel more emotionally connected to their clients and, arguably, better able to deter them from criminal backsliding.

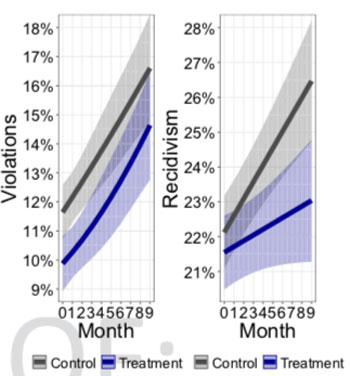

The findings, published today, March 29, in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, show, on average, a 13% decrease in recidivism among the clients of parole and probation officers who participated in the UC Berkeley empathy training experiment.

“If an officer received this empathic training, real-world behavioral outcomes changed for the people they supervised, who, in turn, were less likely to go back to jail,” said study lead and senior author Jason Okonofua, an assistant professor of psychology at UC Berkeley.

The results are particularly salient in the face of nationwide efforts to reduce prison and jail populations amid a deadly pandemic and other adversities. The U.S. criminal justice system has among the highest rates of recidivism, with approximately two-thirds of incarcerated people rearrested within three years of their release and one-half sent back behind bars.

“The combination of COVID-19 and ongoing criminal justice reforms are diverting more people away from incarceration and toward probation or parole, which is why we need to develop scalable ways to keep pace with this change,” said Okonofua, who has led similar interventions for school teachers to check their biases before disciplining students.

How they conducted the study

At the invitation of a correctional department in a large East Coast city, Okonofua and graduate students in his lab at UC Berkeley sought to find out if a more caring approach on the part of court-appointed supervision officers would reverse trends in recidivism.

Among other duties, parole and probation officers keep track of their clients’ whereabouts, make sure they don’t miss a drug test or court hearing, or otherwise violate the terms of their release, and provide resources to help them stay out of trouble and out of jail.

For the study, the researchers surveyed more than 200 parole and probation officers who oversee more than 20,000 people convicted of crimes ranging from violent crimes to petty theft. Research protocols bar identifying the agency and its location.

Using their own and other scholars’ methodologies, the researchers designed and administered a 30-minute online empathy survey that focused on the officers’ job motivation, biases and views on relationships and responsibilities.

To trigger their sense of purpose and values, and tap into their empathy, the UC Berkeley survey asked what parts of the work they found fulfilling. One respondent talked about how, “When I run across those guys, and they’re doing well, I’m like, ‘Awesome!’” Others reported that being an advocate for people in need was most important to them.

As for addressing biases — including assumptions that certain people are predisposed to a life of crime — the survey cited egregious cases in which probation and parole officers abused their power over those under their supervision.

Survey takers were also asked to rate how much responsibility they bear, as individuals and members of a profession, for their peers’ transgressions. Most answered that they bore no responsibility.

Ten months after administering the training, researchers found a 13% decrease in recidivism among the offenders whose parole and probation officers had completed the empathy survey.

While the study yielded no specifics on what prevented the parolees and people on probation for reoffending in the period following the officers’ empathy training, the results suggest that a change in relationship dynamics played a key role.

“The officer is in a position of power to influence if it’s going to be an empathic or punitive relationship in ways that the person on parole or probation is not,” Okonofua said. “As our study shows, the relationship between probation and parole officers and the people they supervise plays a pivotal role and can lead to positive outcomes, if efforts to be more understanding are taken into consideration.

Co-authors of the study are Kimia Saadatian, Joseph Ocampo, Michael Ruiz and Perfecta Delgado Oxholm, all at UC Berkeley.