UC Berkeley Teams Nab Top Prizes at National Affordable Housing Competition

After years of campus teams coming tantalizingly close to first place, an interdisciplinary group of graduate students won the top honor for a housing development plan that balances feasibility with innovation.

Near the edge of Florida, in unincorporated West Palm Beach, an area that has weathered two major hurricanes in the last year, a boxy, off-white housing complex called Dyson Circle Apartments fills 13 uninspired acres. It was built in 1975 and, according to the young, mostly Black and single-parent families who lived there, its 134 units had not seen much renovation since.

“A local told us that no one really wanted to live in Dyson Circle; everyone wanted to leave,” said Yameen Arshad, a 2025 graduate from UC Berkeley’s master of real estate development and design program.

Transforming Dyson Circle into an appealing complex that would withstand climate change and offer its low-income residents the kind of community programming they wanted, all while working with constrained funding sources and keeping the community affordable — that was the task at hand for Arshad and the nine other Berkeley students who competed in the national 2025 Innovation in Affordable Housing Student Design and Planning Competition.

The two interdisciplinary Berkeley squadrons, Team Blue and Team Gold, began contemplating how they might redevelop Dyson Circle in December. The high-profile contest offers prestige, connections with advisers and jurors in the affordable housing industry and crucially, a chance to apply classroom learning to a real-world scenario so complex it can feel labyrinthine. In the competition, teams must propose fully redesigned buildings, landscapes and community programming; develop a plan for getting neighborhood and municipal support; and work out financial projections that incorporate a carefully calibrated mix of funding sources. Then, after incorporating feedback from the jury in a first-round review, they must return to present and defend their finished designs.

“Often students will tell me when they’re graduating that this [competition] was the most satisfying moment of their tenure,” said Ben Metcalf, one of Berkeley’s faculty advisers for the contest. Now a professor with the Department of City and Regional Planning and managing director of the Terner Center for Housing Innovation, Metcalf once worked at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), directing the agency’s office of multifamily housing. He said the Dyson Circle scenario mirrors the type of tight-timeline, budgetarily constrained projects that professionals routinely encounter when governmental agencies issue a request for proposals for a site.

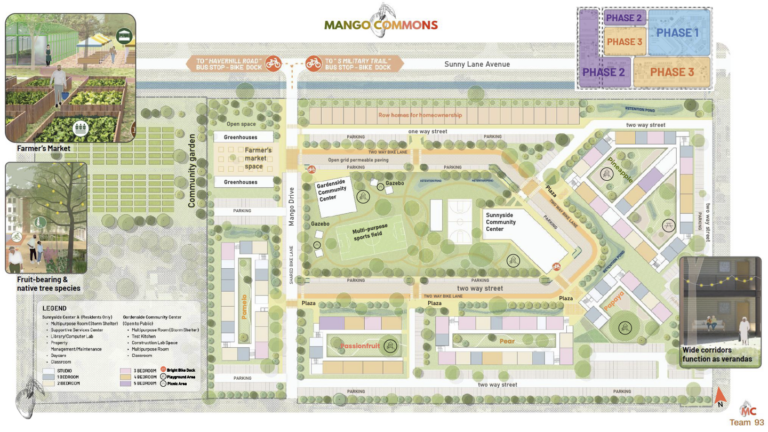

The winning group, Team Blue, put forth a plan to turn Dyson Circle into Mango Commons, a transformation that would take seven to eight years and $157 million. They more than doubled the number of dwellings in the community, with apartments ranging from studios to five-bedroom units nested in five buildings, each one named after a tropical fruit, like pomelo or papaya. The development would also have 24 row houses that residents could help build — and then own — in partnership with Habitat for Humanity.

Team Blue consisted of Arshad; Omeed Ansari, a master’s recipient in real estate development and design; Balaji Balaganesan, a master’s recipient in city planning; Harrison Haigood, an MBA candidate; and Chelsea Hall, a master’s recipient in public policy. All but Haigood, who still has two more years of his program, graduated this May. Each team member brought individual expertise to a different part of the project, and the team held countless Zoom meetings over winter break. “It became our lives. Because we cared,” Arshad said.

Among the thorny questions the team tackled together: How to best arrange the units, Tetris-like, to fit the most number of residences on the property without ballooning the budget? How might shifting federal policies change their funding sources? Could they speed up construction using prefabricated materials? What design choices would best protect inhabitants from harsh winds and hurricanes?

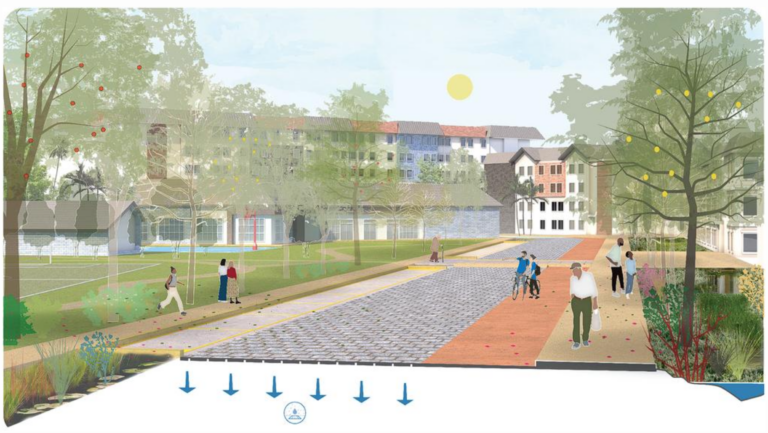

For the hurricane question, they chose hardy materials like impact-resistant roofing and prefabricated concrete walls and positioned the buildings to minimize wind tunnels. For flood mitigation, they proposed retention ponds and open-grid paving to soak up water. They addressed Florida’s humid climate with shaded breezeways between units, added trees to lower the temperature and suggested landscaping with native peanut grass instead of water-thirsty green grass.

Led by Hall, who reached out to a plethora of organizations in the Palm Beach area, they suggested a slew of collaborative programming aimed at fostering community and addressing residents’ requests for child-friendly amenities, such as numerous playgrounds and onsite daycare, robots that residents could program to help water and weed the site’s 50 garden plots, and a test kitchen where youth could cultivate culinary skills.

“In addition to disaster resilience, the planning very much catered to who was already living there,” Arshad explained. “No matter what, you could still feel like you have a home that you can come back to and have good memories in.”

To truly understand the needs of the community, Team Blue consulted with a local cultural anthropologist, who helped them understand the culture of Dyson Circle, where the average income is $15,002, as well as the surrounding suburban neighborhood of West Palm Beach, which sits just blocks from the airport and skews young and racially diverse. They also took the enterprising step of contacting current residents personally to gain insight into their experiences, gripes and all, at Dyson Circle.

As a result of what they heard, the team went all-in on youth-friendly programming, added more trees to the landscape — bringing the total to more than 300, in comparison to the original 80 — and devised a plan to add on-demand bike docks to help residents get to the nearest bus stop. They also made sure the buildings had covered verandas in a nod to the social “front porch culture” of the South.

The site map they submitted shows a community garden and space for a farmer’s market to sell the produce grown on-site, bike lanes, a sports field, a basketball court and ample green space dotted with, in some renderings, outdoor string lights. The two community centers, which host a library, computer lab and classroom, among other amenities, double as storm shelters.

Team Blue and Team Gold initially partnered up to do background research on the site and surrounding area, but they devised different solutions to the same affordable housing riddle. “Golden Palms,” as Team Gold named its project, had slightly fewer units, at 285. To address the threat of a hurricane, they proposed a marsh park to absorb flooding and buildings mounted on concrete podiums. Like Team Blue, they created programming for residents: in this case, kitchen and masseuse training and a construction lab that could be used for fun or professional training. They worked out what kind of staff they’d need for their 70-seat daycare center, suggested a resident leadership council and proposed amenities for seniors like free massages from the masseuse training program.

Golden Palms, like Mango Commons, included a homeownership plan, which they imagined as 10 townhomes that renters could eventually purchase after 15 years of residency, with their lease payments reducing the home’s purchase price.

A core challenge of the competition, Metcalf said, is striking a balance between bold innovation and achievability. “I actually think both of these Berkeley teams nailed it,” he remarked. “They basically said, ‘We’re going to figure out how to do a very cost-effective building with a very basic unit type that stacks,’ but then they spent really good thought on ‘Let’s have some marquee façade elements and some ennobling community spaces that really sizzle.’”

Evidently, the competition’s judges agreed, awarding Team Blue the $15,000 first place prize and Team Gold the $5,000 second place honor. The dual victories were long-awaited, Metcalf said. Over the past six years, Berkeley teams had gotten tantalizingly close, thrice placing as the runners-up.

But the Berkeley cadre’s victory was far from assured. In fact, a few days before the finalists were announced, Metcalf received a terse alert that the contest had been terminated by its traditional sponsor, HUD. “[The students] had put heart and soul into the proposals … when HUD pulled the plug, it just felt gut-wrenching and so arbitrary,” he recalled. So he said he took action: “Literally within hours of getting this notification, I was working the phone.”

Eventually, after figuring out how to contact the contractor who’d been running the program for HUD, Metcalf found a national organization willing to host the contest: the Council of Large Public Housing Authorities. In a turbulent political environment for affordable housing, adopting the contest could have been a tough sell, but fortunately, the board chair had been involved in the competition several years prior, as the Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority had provided the “test case” the student designers addressed. However, while the organization agreed to donate staff time, it did not have funds in place to cover the added costs that came with the competition.

Housing is a human right at the end of the day for me.”

Omeed Ansari

Metcalf, along with the Berkeley teams’ faculty advisers, Lydia Tan and Claire Parisa, as well as College of Environmental design lecturer Ann Silverberg, pieced together funding pledges from a dozen different sources to underwrite the competition. Improbably, two months after the cancellation, the race was formally back on, and Team Blue and Team Gold busied themselves once again with renderings and spreadsheets.

This month, Team Blue presented its proposal to public housing leaders and advocates from around the country as well as to the Palm Beach County Housing Authority, which will take the design into consideration as the real-life Dyson Circle gets redeveloped. While the long-term future of the competition remains up in the air without HUD as its permanent sponsor, the Berkeley participants agreed that the chance to apply their classroom learning in this fashion has been invaluable.

In his new job for the Santa Clara County Housing Authority, Ansari will be drafting the same kinds of funding scenarios he did for this competition. “Housing is a human right at the end of the day for me,” he said. “That’s the mantra I live by and I work by, and our whole team goes by that.”

Arshad echoed those sentiments. She hopes to eventually bring her experience in affordable housing design and development to her home country of Pakistan, where new, inexpensive dwellings are much needed.

“As a developer, you can create such a big impact, negative or positive,” she said. Mango Commons is one such step toward making a brick-and-mortar impact for good.