UC Berkeley Researchers Investigate Why So Many Students Are Chronically Absent

The multi-year project partners with San Francisco students to design and interpret studies exploring chronic absenteeism — and explore how young people can be part of the solution.

Inadequate public transportation options. Needing to work and take care of family members. Bullying and anxiety. Feeling too far behind to catch up and a lack of a sense of belonging.

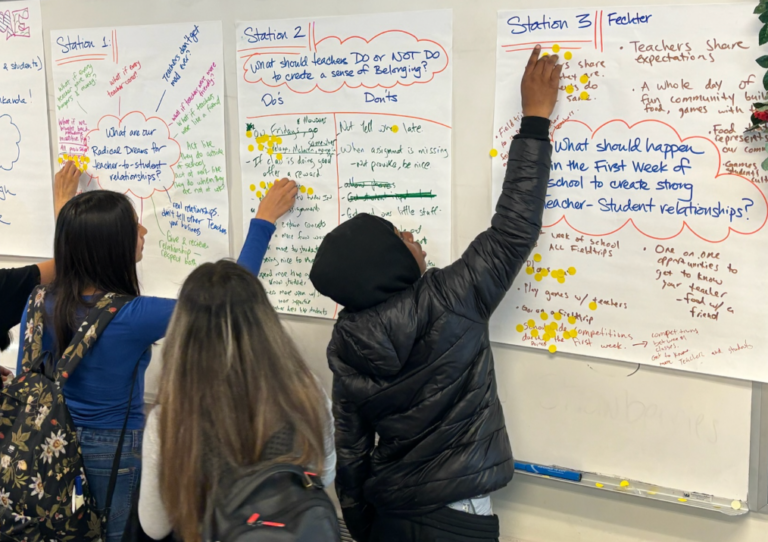

Middle and high school students face numerous challenges that cause them to miss significant amounts of class. But on a recent afternoon at UC Berkeley, it wasn’t esteemed faculty members or education policy experts who led a presentation about the latest causes of chronic absenteeism in San Francisco public schools.

It was the students themselves.

For the past five years, students in San Francisco’s public middle and high schools have worked alongside Berkeley researchers to explore the root causes of chronic school absenteeism and the conditions that support belonging.

Roughly one in five students in the San Francisco Unified School District was chronically absent last year, meaning they did not attend at least 10% of instructional days, according to state attendance data. That’s up from one in eight the year before the COVID-19 pandemic upended education globally. The rate was even higher for historically marginalized groups, including Black and Hispanic students. At some schools, more than half the students are chronically absent — all challenges this district has long sought to address.

It’s not just San Francisco. Rates of school absences have increased nationwide in recent years, often with complicated explanations. And while those rates have trended downward from pandemic-era Zoom school, the stubbornly high figures point to a profound amount of learning loss that can set students back academically and in life.

“Students who are chronically absent are less likely to graduate, with long-run challenges for employment, health and well-being across their lives,” said Emily Ozer, a psychologist and professor at Berkeley’s School of Public Health. “Since it’s such a major problem affecting young people and schools, with learning outcomes and budgets tied to student attendance, it is vital to partner with students in solving the problem.”

Ozer and her colleagues are co-leading the unique collaboration between Berkeley researchers and San Francisco students, who are involved in everything from forming research questions to interpreting results. Together, the adult and student teams have examined the drivers of chronic absenteeism and why some kids miss so much more school than others.

Soon after it launched in 2020, the collaborative project revealed new details about students not feeling safe in — and on their way to — school. Inadequate public transit and a lack of mental health support also fueled much of the absenteeism issue. While these were generally acknowledged issues before, students’ firsthand experiences added new understanding to the problem, Ozer said.

“In the last decade, there’s been a huge blossoming of this kind of youth-voice research in many parts of the country,” said Ozer, who is also Berkeley’s faculty liaison to the provost on public scholarship and community engagement. “But SFUSD has been unique in terms of the commitment to seeing this evidence as a form of data for evidence-based decision-making.”

It is vital to partner with students in solving the problem.

Emily Ozer

Traditional research teams often approach communities with pre-determined scholarly questions, collect and analyze data and publish their findings. Increasingly, however, researchers focused on strengthening the societal impact of their research are using community-engaged approaches, where scholars and community groups work together to draw up questions, form research plans, collect and analyze data and implement suggested changes.

This kind of research partnership can draw on the expertise of people with direct experience — from students and families to policymakers — to inform the research at the outset and along the way. It can also build needed trust among researchers and communities, said Ozer, who aims to call attention to community-engaged research as one of Berkeley’s greatest strengths.

Collaborative approaches can enhance the quality and relevance of research, and Ozer said the project with SFUSD is “a model for how we do this in authentic and impactful ways.”

“We see this as one of multiple potential signature initiatives for campus,” Ozer said. “And we are thinking about how the learning here connects with other core, important partnerships happening locally.”

Extensive research history with SFUSD

Ozer and Susan Stone, dean of UC Berkeley’s School of Social Welfare and a project co-leader, both have deep research connections with the San Francisco school district.

More than 20 years ago, Ozer began working with San Francisco Peer Resources, a youth development organization that supports young people working to improve their communities and schools. Around that same time, Stone began working with the district on a project studying school-based health centers and how social workers and nurses could improve student health.

Ozer and Stone were each asking similar questions, but they were going about them from different angles.

Then, at an event in 2018, students from a Peer Resources team presented their latest findings from a year of interviews. Over lunch that afternoon, Ozer and district research leaders began brainstorming ways to strengthen the district’s learning from student-led research in its approach to school improvement and evaluation. What if there was an opportunity to combine their projects? Could a collaborative partnership both assess attendance policy and benefit more from students’ expertise? Could the integration of district administrative data and youth-led research help draw up possible solutions?

Students, they reasoned, were generating evidence about what was going on. The problem was deciphering what it all meant and how best to put it into practice. That conversation launched the collaboration that’s still evolving today.

“It felt very intentional from the start,” said Devin Corrigan, SFUSD’s supervisor of analytics and liaison with the city. “There was a lot of comfort with not knowing where we were necessarily going to end up and trusting the process.”

‘Young people have something to say’

Spend any amount of time at education conferences and you’ll likely hear a presentation about the importance of having young people included in institutional decision-making. The SFUSD Student Advisory Council provides youth input on district policies. Elsewhere, the cities of Berkeley and Oakland recently began allowing teenagers to vote in city elections for school board.

What’s been less clear is how to include young people’s voices in the academic research process. Adults may have ideas about why students miss class, but young people know firsthand what’s going on and can glean information that adults might miss.

“We believe that young people have something to say and that their voice matters,” Corrigan said. “When the adults in the room are making the decisions around policy, they are a part of the evidence base that needs to be included.”

Because we work together — that’s the definition of engaged research — there’s more impact.

Susan Stone, dean, UC Berkeley School of Social Welfare

The Berkeley-SFUSD partnership, with support from the William T. Grant and Doris Duke Foundations, has grown to include hundreds of high school students who develop their own research questions and gather data using methods like surveys, interviews or observations. Stone leads the team analyzing administrative records and programs, and Ozer leads the team that helps support student-led research. Together, the UC-Berkeley and SFUSD teams also raise awareness and integrate student-led research to improve understanding and policies that strengthen school climate and reduce attendance barriers.

In the 2023-24 school year, SFUSD Peer Resources student researchers conducted 17 projects across eight of the district’s middle and high schools. One project engaged students with disabilities, who identified ways to improve support services and resources. In response, the school launched a student-led podcast and poster campaign to spread awareness about accommodations for students with disabilities — solutions that came to light because of the collaborative research.

“Because we work together — that’s the definition of engaged research — there’s more impact,” Stone said. “There are more contributors, and there’s a broader range of outcomes.”

The team is also attempting to build a platform that will help tell the story of nearly a decade of youth-led research in a way that can inform school and district interventions and action, said Brian F. Villa, a UC Berkeley Institute of Human Development postdoctoral researcher.

“This approach really elevates young people as living experts who are also valuable sources of wisdom,” Villa said. “Students are researching and addressing issues that they really care about. And often those are the same issues that the adults are also concerned about.”

Corrigan agrees. And he’s hopeful that in the years ahead, the research can help refine attendance policies and inform interventions that can put a serious dent in absenteeism.

“It feels like we’re on the precipice of something really great here.”