In a Time of Tense Division, We Must See the Humanity in Our Opponents

With U.S. democracy hanging in the balance, the leader of UC Berkeley’s globally influential Othering and Belonging Institute urges that, whenever possible, we build bridges — even with those who traffic in hate.

As a storm of uncertainty and anxiety reaches its peak before Election Day, john a. powell is focused on a choice confronting all Americans — a choice arguably deeper and more difficult than a vote for Vice President Kamala Harris or former President Donald Trump.

Will we see our opponents as the other, and become so bitterly alienated that we break apart into separate communities, locked in constant conflict? Or will we somehow find a way to build bridges across our angry divides, and to build communities where everyone belongs?

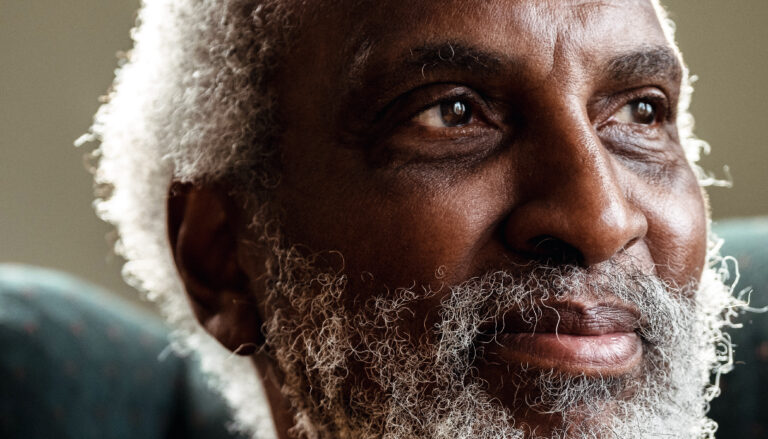

powell, director of the Othering and Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley, is a veteran activist and scholar in civil rights and social justice, and in a recent interview with UC Berkeley News, he was not naïve about the racism, sexism and other threats to democracy embedded in the 2024 presidential election. But after decades of teaching and research in the U.S. and overseas, he has come to believe that bridging and belonging are the essential routes to a hopeful future.

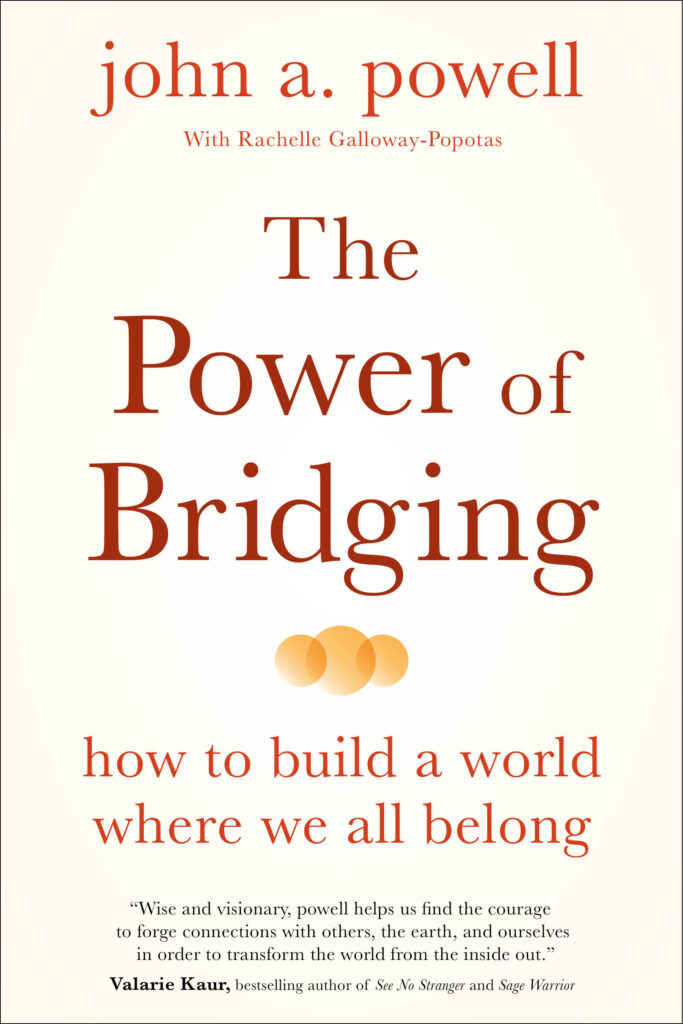

That’s the central idea in his forthcoming new book, The Power of Bridging: How to Build a World Where We All Belong (Sounds True, Dec. 3, 2024). In part thanks to powell’s leadership, Berkeley has emerged as a national center of innovation in “bridging,” a set of values and practices that encourage constructive engagement and healthy disagreement to build a more just and inclusive society.

powell is an internationally influential thinker, and holds distinguished positions at Berkeley: professor of law, professor of African American studies and ethnic studies, and chancellor’s chair in equity and inclusion.

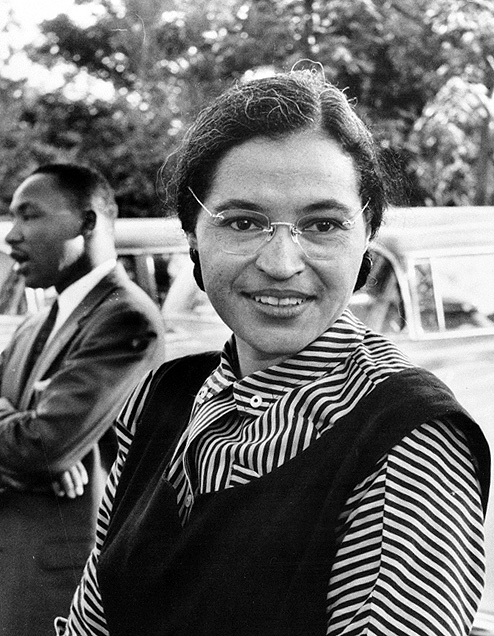

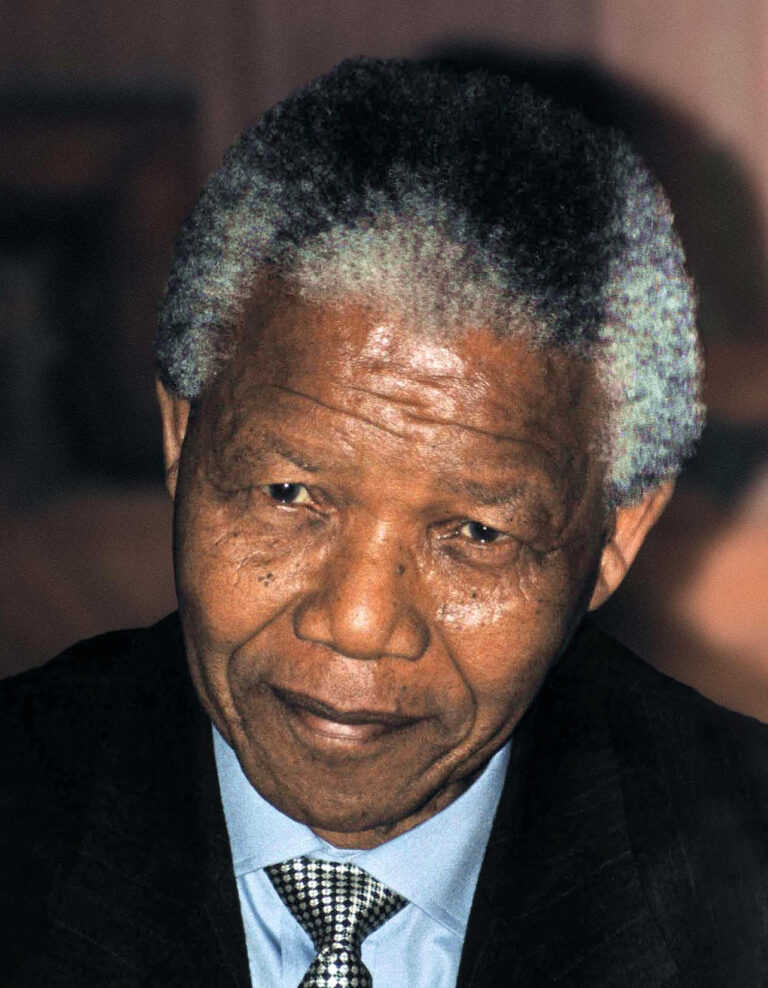

In the interview, he cited the thinking of civil rights pioneer Rosa Parks and two winners of the Nobel Peace Prize: the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., the U.S. civil rights icon, and Nelson Mandela, who led efforts to dismantle racial apartheid in South Africa. It is as if powell has taken their ideas into his core, and now is working to apply them in the most challenging conditions in modern American history.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Berkeley News: The question top of mind for most people right now is the presidential election. When you look at the election through the lens of othering and belonging, breaking and bridging, what do you see?

john a. powell: It’s not just an election. It’s not just Democrats versus Republicans. You know, I probably lean more toward Democrats most of my life, but not entirely. Actually, I have much respect going back to the Rockefeller Republicans, but also Colin Powell [the late army officer and statesman] and others. And even people like U.S. Senator Mitt Romney, more recently. So I have ideals, but I’m not an ideologue.

What’s happening now — as a number of Republicans have said themselves, Trumpism is not Republicanism. There really is a cult, and the cult is basically anti-democratic. There’s a quality of not caring about the idea of democracy, but also not caring about the institutions. Everything is about personal gain.

I’m sure conservatives have complained about Democrats playing politics. But I think people who are honest will look at it and say that Trumpism is at another level. You think of presidents being brought down by sexual misconduct, but not Trump. He can brag about it, and it hasn’t hurt him. And so the election, to some extent, is about our democracy.

When you think about the Muslim ban, before it was cut down by the court, there was a kind of institutional othering. His own advisers said, “Stick to the issues.” But he said, “No, I want to make this personal.” If you follow some of the attacks coming toward Vice President Harris, a lot of them are misogynistic. That’s not politics in any normal sense. That’s not recognizing someone’s humanity, even if you disagree with them.

This is saying: These people are not equal. We can say anything about them.

Considering the cause of our polarization: Do you think that what’s going on, particularly on the MAGA side, is to any extent a response by MAGA adherents to feeling othered, in a sense, in what they think of as their own country?

That’s part of it. My colleague, Arlie Hochschild, wrote her book, Strangers in Their Own Land (2018, The New Press). I respect Arlie’s work, and I think she pulled back a curtain so we could observe things. But there’s obviously the question: How did this become their country?

I mean, it’s not the Native Americans’ country? The Black people who built the country — it’s not their country? The Latinos who were here before Blacks and whites — is it their country?

It’s a kind of grievance. White people, white men, middle-class men, even upper-middle-class men, feel like they’re losing something as well. At the foundation of that, there are two things going on. There’s a desire to belong. And so this assumption that we’re going to go back to where we did belong, and where we were in control. But my belonging cannot be predicated on your not belonging. And that’s what this is about.

There’s something going on that is not reducible to Trump. What’s going on, in part, is this deep, deep anxiety about the future.

john a. powell

That is just another version of us versus them.

When people talk about the economy being stalled for 40 years, I think it’s largely true, but it’s stalled not just for white men — it’s stalled for white women and stalled for Blacks, it’s stalled for Latinos. But a core group — it’s not just white men, and it’s not all white men — there’s an entitlement built into that grievance. There’s an assumption: “We’re supposed to have everything that we had, there’s no history to our accumulation of wealth, to our dominance, to our control — we earned it.”

Now you have some people who are questioning the very concept of equality. They say, “We’re going to stop talking about equality, the world’s never been equal, and some groups are naturally superior to others,” i.e., white men. That sentiment is being expressed by powerful people. Fortunately, it does not represent the majority of Americans.

And it’s not just happening in the United States — it’s happening all over the world. So I think there’s something going on that is not reducible to Trump. What’s going on, in part, is this deep, deep anxiety about the future.

Do you think people are feeling more free to state these ideas openly and at high levels than they were 20 years ago, or a half-century ago?

Go back to 2000, and before, and the idea of quote-unquote identity politics. Marginalized groups had strong identities, and we had all these attacks against identity politics. “You should not be organizing around a race or gender,” which is easy to say if you are in the dominant group.

Amartya Sen, the Nobel economist, points out that when you are marginalized and threatened, the basis of that marginalization or threat will cause you to deeply identify with that identity. If you attack someone because of their sexual preference, the sexual preference can become extremely important to them on an organized level.

Now what we’re having is, in a sense, the concept of whiteness, the concept of Christianity, apparently feels a threat. And this group historically had been the group that pushed, “We don’t care about race. We don’t care about your religion.” Now they do care. It’s pretty clear they care more and more.

The fact that you can have the Proud Boys marching in South Carolina and being lifted up, you can have people storming the Capitol on January 6th, and the Republican Party, as it’s now constituted, refuses to call this an insurrection. And the few that did — for example, Liz Cheney — are actually pushed out of the party.

That’s new. We’re entering uncharted territories. And how deep it is and how normalized, that’s hard to say.

Even if these folks take up a lot of air space, the percentage of white people who believe they have a right to dominate, and are superior, represents a small percentage of the white population. Although they are punching above their numeric weight, we should not lose sight of the fact that they are a minority.

I keep running up against this doubt: There are some people on the other side of the divide, but they don’t want to build a bridge. They want to defeat the people they oppose. They want to dominate. They might be white supremacists. They might be misogynistic. Is it even possible to engage with these folks in a constructive way?

That’s a really important question. First of all, I think sometimes we may choose not to bridge. Bridging is not going to solve bad faith — bridging doesn’t do everything.

But even in war, there comes a time when people need to talk. Unless you’re going to commit mass genocide against everybody who’s outside your group, or you’re seeking complete domination, you’re going to have to talk. That’s the practical level.

But there’s a deeper level, a spiritual level. We have some challenges, but so did Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. So did Rosa Parks. So did Nelson Mandela, in South Africa. Mandela is instructive. I had the opportunity to meet him when he was out of prison and obviously trying to heal not just himself, but the whole country. He was a lovely man.

At the time he was negotiating the peace treaty in South Africa, literally, friends, family, comrades were being killed every day. When he negotiated the peace, initially, a general that he set out to meet with was publicly calling him a monkey, saying Black people were inferior. He was saying that whites could win, and there was a duty and obligation to win — it was the protection of Western civilization. He was saying all the things, and he had an army behind him.

Mandela entertained that general in his house. And the negotiation took place in Afrikaans, which was the general’s language. Mandela had actually learned Afrikaans while he was in prison, from the guards.

Instead of focusing on those who refuse to bridge, we have to focus on those who are willing, even if they are reluctant.

Many people would understand that, in principle. But in practical terms, how do you do it in a time of such tension, where divisions are really acrimonious?

There may be some conditions that we set before we try to bridge. I would talk to anyone, but I do have conditions. One of them is: no violence. I’ve been in situations where people wouldn’t meet that condition, and I didn’t talk to them.

King talked about this. Mandela talked about it. They’re inspirations for the idea that we don’t need perfect conditions for dialogue. But things are almost never as bad as we think.

We talked about the people who are cult followers of Trump. A lot of people are probably in a softer position. And what’s driving that? I think, by and large, it’s the fear of not being seen, and not belonging.

They say people feel disrespected? Well, respect them. We should talk to people who are in the exhausted middle. We need to understand them — not what their position is on abortion, not their position on immigration, but their deep, heartfelt fears and aspirations for their family, for the community and the country.

In that, the possibilities of bridging are much, much greater.

But again, in practical terms, it seems so difficult sometimes, when divisions over race, gender and sexual identity are so tense, and seemingly so volatile.

We talk about short bridges and long bridges. We say: Start with the short bridge.

I was talking to Pastor Michael McBride, a local pastor in the Bay Area. When I talked about bridging, he said: “So john, let me be clear — are you suggesting that we bridge with the devil?” I said: “Pastor McBride, I don’t suggest you start there.”

Don’t start with the longest bridge, and even short bridges can be challenging. But also be careful who you call the devil. We have to learn to bridge with the apparent other, and our fears.

At the Othering and Belonging Institute, we work with Search for Common Ground in war-torn areas, with people who literally have been involved in killing each other’s families. And yet, under some conditions, they can still come together and talk. They can still come together and see each other’s humanity. That’s not enough by itself — we have to think of the guardrails, institutional culture, the incentives and disincentives to bridge and to break. That’s the work to be done.

We work with a group called CareLab, and we’ve been helping to bring together Democrats and Republicans, at a fairly high level, for years. We create a chance for people to come together as people. If we can recognize each other’s humanity, it doesn’t mean we will agree. But how far can it go? We don’t know.

Not long ago, we had more people in the streets caring about George Floyd — most of them not Black — than in any time in U.S. history.

Yes, but his murder also reflected a really discouraging racial hostility that persists among many communities in America.

We should remember that Trump followed Barack Obama. At that time, a lot of people were saying that we’re moving into a post-racial world, we’ve solved the problem. I spoke at the convention when Obama was nominated, and I said: “I doubt it.” Research suggests that it’s more insidious, more complicated than that.

There is this underlying anxiety. Every time you hear about whites not being in the majority, anxiety in the country goes up. But part of that anxiety for most people is fear that they will not have a place, that they will not belong. Belonging is what’s driving it. So belonging is being used to create othering.

Can we create belonging without othering? We have to try. This is something we all have to take on.

We’re not doing this because we’re going to convince the other side, and not because they’re open to it. We’re doing it because we’re bridgers — that’s who we are. That’s who we want to be as human and spiritual beings on this planet. And if we fail — not individually, but collectively — then the human experiment, I think, will fail.

You referenced a spiritual awakening, a renewal of our values, that could help get us to this place of openness. Is there a model for how this might work?

One of the powerful examples, which a lot of people don’t like me using, is the military. In the 1960s and ’70s, at the height of the Vietnam War, there were race riots all over the country. Think about it: In the 1960s, we’re going to take 18-year-olds from rural Alabama, from inner-city Chicago and from inner-city Los Angeles, and give them guns and put them in close proximity with each other.

It sounds like a dystopian movie. And it was, until the military said: How do we build relationships with these folks? The military took upon itself to create real camaraderie, to create real caring, to create real bridges.

Even in war, there comes a time when people need to talk.

john a. powell

Bridging and being open, yes, it creates a certain vulnerability. It’s like Leonard Cohen wrote, “The crack is how the light gets in, the crack is how air gets in.” If we are completely closed off to each other, we’re already dead.

So when we do this, it’s not just rhetoric. It’s not just hard work. It’s actually joyful. We live in an incredible place and time. And although the fragmentation and polarization are growing, so is something else. People have tremendous capacity, but which of those capacities gets lived out?

Leadership matters, but we have to wait for an emerging leader. Just like Donald Trump gave voice to grievances among some white people — and not just white people, but mainly — there can be someone who can give voice to caring about all of us. I’m hoping that happens and, in fact, I’m hoping we demand it.

I say to people, “The day after you win the election, what happens to the 46, 48, 49% who voted the other way? What happens to them?” We have to care about those who we would call the losers.

Which brings us back to your core idea about the importance of belonging, a need shared by all people.

This deep anxiety that we’re experiencing and that gets exploited — if I’m right, it’s in part being fueled by change. We fear that we won’t belong in this emerging world. In that sense, it may not matter as much as who wins — Democrats or Republicans, liberals or conservatives. That deep anxiety about change is still going to be with us.

And change is happening at an accelerating pace: Climate change. Pandemics. Artificial intelligence. We’re entering a world full of anxiety. How do we belong in that world?

Well, we will have to change. It’s absolutely clear to me that our best chance of dealing with that is to turn toward each other, rather than turn on each other. You’re not in control of AI, and if I blame you for my anxiety, that’s a mistake. You have anxiety, too.

In moving toward bridging and solutions, we have to be very careful not to diminish the other, not to simplify them. The white supremacist is not just a white supremacist. He/she/they have children, and they have concerns. They have loves. They have loss. We all have these concerns.

We can face the future together, and maybe not control it, but influence the future together. We do this by listening to each other and the earth. We do this by being curious and caring.