Success Treating Night Blindness in Dogs Could Lead to Human Gene Therapy

Scientists have successfully restored dim-light vision to dogs with an inherited disorder that causes night blindness, a major step toward using the same gene therapy to help people with similar vision problems.

In 2015, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Veterinary Medicine learned that dogs could develop a form of inherited night blindness with strong similarities to a condition in people called congenital stationary night blindness (CSNB). People with CSNB are unable to distinguish objects in dim-light conditions, which presents challenges when artificial lighting is unavailable or when driving at night.

“The term ‘stationary’ refers to the fact that this very impaired vision in dim light occurs at birth and doesn’t get better or worse with time, which makes it quite debilitating for patients,” said neuroscientist John Flannery, UC Berkeley professor of molecular and cell biology. “There is currently no treatment for these people.”

In 2019, when the Penn Vet team identified the defective gene responsible for CSNB in dogs, the researchers reached out to Flannery to find a way to deliver a replacement gene — a normal copy of the defective gene — into dogs’ retinas.

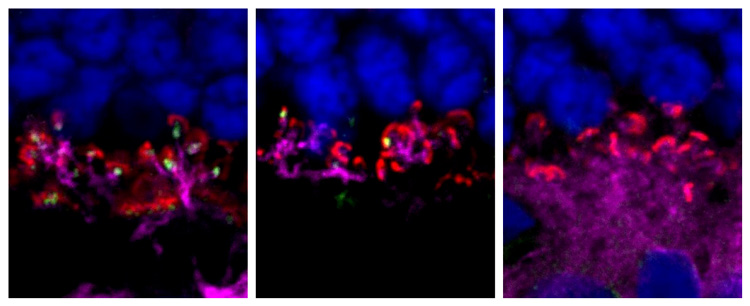

Flannery and former postdoctoral fellow Leah Byrne, now an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh, designed and made a viral vector that could target the defective cells and deliver the gene. When injected into the retina, the virus — an attenuated adeno-associated virus (AAV) — would carry the replacement gene and a cell-specific promoter into ON-bipolar cells in the retina, which receive visual input exclusively from rods, which are the cells sensitive to dim light and the site of the mutated gene in these dogs.

This week, the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences published the team’s paper reporting its successful restoration of night vision to dogs born with CSNB.

“In videos of the dogs after the treatment, the restoration of vision in low lighting is quite impressive and easy to appreciate in the canine behavior,” said Flannery, a member of Berkeley’s Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute and a faculty member in the Herbert Wertheim School of Optometry and Vision Science. “The defect is in the synapse between the rod photoreceptor and the rod-specific bipolar, and this has only been attempted before in mice.”

Dogs with CSNB that received a single injection of the gene therapy began to express the healthy gene in their retinas and could ably navigate a maze in dim light. The treatment also appears lasting, with a sustained therapeutic effect lasting a year or longer.

“The results of this pilot study are very promising,” said Keiko Miyadera, lead author of the study and an assistant professor at Penn Vet. “In people and dogs with congenital stationary night blindness, the severity of disease is consistent and unchanged throughout their lives. And we were able to treat these dogs as adults, between 1 and 3 years of age. That makes these findings promising and relevant to the human patient population, as we could theoretically intervene, even in adulthood, and see an improvement in night vision.”

The gene that the Penn Vet team corrected to fix the dogs’ night vision impairment has also been implicated in certain cases of human CSNB, which opens the door to treating people with a similar gene therapy.

While the therapy enabled functional recovery in the animals — the dogs were able to navigate a maze when their treated eye was uncovered, but not when it was covered — the healthy copy of the gene was expressed in only 30% or fewer of ON bipolar cells. In follow-up work, the researchers hope to augment this uptake for future dog and human trials.

“We’ve stepped into the no man’s land of the retina with this gene therapy,” said William A. Beltran, a co-author and professor at Penn Vet. “This opens the door to treating other diseases that impact the ON bipolar cells.”