Study links Texas earthquakes to wastewater injection

A new study co-authored by UC Berkeley professor Michael Manga confirms that earthquakes in America’s oil country — including a 4.8 magnitude quake that rocked Texas in 2012 — are being triggered by significant injections of wastewater below the surface of the Earth.

While there has been plenty of speculation that the alarming increase in seismic activity in states like Texas, Oklahoma and Arkansas were a result of human activity, the study — which appears in the journal Science — fingers deep wastewater injections as the culprit.

“The proximity of the earthquake clusters to the injection wells suggests a link between them,” researchers explain in the report. “As wastewater is injected into the disposal formation, it increases pore pressure within the system… The increase in pore pressure caused by the injection of fluids decreases the effective normal stress on faults, bringing them closer to failure.”

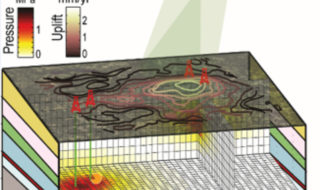

The study details how Manga and his colleagues used interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) and GPS to detect small — no more than a few millimeters — but significant increases in surface elevation near four wells in East Texas. The surface uplift is likely the product of an increase in pore pressure — the pressure of fluids in the soil or rock below ground — caused by wastewater injections.

Wastewater injection wells exist because processes of extracting oil and natural gas from the Earth also yields a tremendous amount of water as well, sometimes exceeding 10 times more water than oil. The water that is extracted is saline and contaminated, and safe disposal of it is somewhat challenging. The water is too toxic to be introduced back into the water table, so the current disposal solution is re-injecting it back underground through these disposal wells. The four wells observed in this study became functional between 2005 and 2007 and have injected roughly 1 billion gallons of water back below ground.

“One way to think of it is like having a balloon underground,” said Manga. “As water is injected below the surface, the balloon expands, which increases the pressure that plays a role in triggering earthquakes.”

The study examined two wells that injected water a little more than a mile below ground, and two that injected water at about half that depth. The depth that the wastewater is disposed of, or the placement of the pressure balloon, plays a significant role in seismic activity.

Researchers found that there was detectable ground uplift in the area surrounding the two shallower wells where the water was being injected above a large, impermeable layer of rock. The increase in pressure was enough to distort surface elevations, but did not clearly factor in triggering earthquakes.

The two deeper wells injected water below this layer. Hundreds of millions of gallons of water were injected below this layer band of impermeable rock, ultimately having an impact on the pressure of “basement rock,” an area more than a mile below the surface where earthquakes form. As pore pressure rose, it sparked activity on an old fault in 2012. Tremors subsided by the end of 2013, when wastewater injections were reduced significantly.

“The findings are significant because they help us understand where earthquakes will happen, why they happen in some places and not others, and when they’ll happen again in the future,” said Manga.