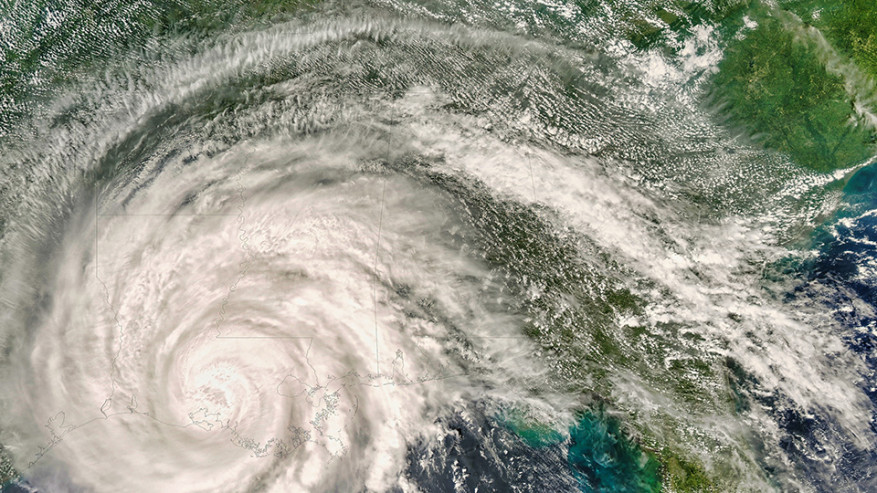

Study Links Hurricanes to Higher Death Rates Long After Storms Pass

U.S. tropical cyclones including hurricanes indirectly cause thousands of deaths for nearly 15 years after the storm. Understanding why could help minimize future deaths from hazards fueled by climate change.

New research reveals hurricanes and tropical storms in the United States cause a surge of deaths for nearly 15 years after a storm hits.

Official government statistics record only the number of individuals killed during these storms, which are together called “tropical cyclones.” Usually these direct deaths, which average 24 per storm in official estimates, occur through drowning or some other type of trauma. But the new analysis, published in Nature, reveals a larger, hidden death toll in hurricanes’ aftermath.

“In any given month, people are dying earlier than they would have if the storm hadn’t hit their community,” said former Goldman School professor (now at Stanford) and senior study author Solomon Hsiang. “A big storm will hit, and there’s all these cascades of effects where cities are rebuilding or households are displaced or social networks are broken. These cascades have serious consequences for public health.”

Hsiang and lead study author Rachel Young, a UC Berkeley postdoc, estimate an average U.S. tropical cyclone indirectly causes 7,000 to 11,000 excess deaths. All told, they estimate tropical storms since 1930 have contributed to between 3.6 million and 5.2 million deaths in the U.S. – more than all deaths nationwide from motor vehicle accidents, infectious diseases, or battle deaths in wars during the same period. Official government statistics put the total death toll from these storms at about 10,000 people.

Hurricane impacts underestimated

The new estimates are based on statistical analysis of data from the 501 tropical cyclones that hit the Atlantic and Gulf coasts from 1930 to 2015, and mortality rates for various populations within each state just before and after each cyclone. The researchers expanded on ideas from a 2014 study from Hsiang showing that tropical cyclones slow economic growth for 15 years, and on a 2018 Harvard study finding that Hurricane Maria caused nearly 5,000 deaths in the three months after the storm hit Puerto Rico – nearly 70 times the official government count.

“When we started out, we thought that we might see a delayed effect of tropical cyclones on mortality maybe for six months or a year, similar to heat waves,” said Young, a postdoctoral scholar at the University of California Berkeley, where she began working on the study as a master’s student in Hsiang’s lab before he joined Stanford’s faculty in July 2024. The results show deaths due to hurricanes persist at much higher rates not only for months but years after floodwaters recede and public attention moves on.

Uneven health burdens

Young and Hsiang’s research is the first to suggest that hurricanes are an important driver for the distribution of overall mortality risk across the country. While the study finds that more than three in 100 deaths nationwide are related to tropical cyclones, the burden is far higher for certain groups, with Black individuals three times more likely to die after a hurricane than white individuals. This finding puts stark numbers to concerns that many Black communities have raised for years about unequal treatment and experiences they face after natural disasters.

The researchers estimate 25% of infant deaths and 15% of deaths among people aged 1 to 44 in the U.S. are related to tropical cyclones. For these groups, Young and Hsiang write, the added risk from tropical cyclones makes a big difference in overall mortality risk because the group starts from a low baseline mortality rate.

“These are infants born years after a tropical cyclone, so they couldn’t have even experienced the event themselves in utero,” Young said. “This points to a longer-term economic and maternal health story, where mothers might not have as many resources even years after a disaster, than they would have in a world where they never experienced a tropical cyclone.”

Adapting in future hazard zones

The long, slow surge of cyclone-related deaths tends to be much higher in places that historically have experienced fewer hurricanes. “Because this long-run effect on mortality has never been documented before, nobody on the ground knew that they should be adapting for this and nobody in the medical community has planned a response,” Young said.

The study’s results could inform governmental and financial decisions around plans for adapting to climate change, building coastal climate resilience, and improving disaster management, as tropical cyclones are predicted to become more intense with climate change. “With climate change, we expect that tropical cyclones are going to potentially become more hazardous, more damaging, and they’re going to change who they hit,” said Young.

Toward solutions

Building on the Nature study, Hsiang’s Global Policy Laboratory at Stanford is now working to understand why tropical storms and hurricanes cause these deaths over 15 years. The research group integrates economics, data science, and social sciences to answer policy questions that are key to managing planetary resources, often related to impacts from climate change.

With mortality risk from hurricanes, the challenge is to disentangle the complex chains of events that follow a cyclone and can ultimately affect human health – and then evaluate possible interventions.

These events can be so separated from the initial hazard that even affected individuals and their families may not see the connection. For example, Hsiang and Young write, individuals might use retirement savings to repair property damage, reducing their ability to pay for future healthcare. Family members might move away, weakening support networks that could be critical for good health down the line. Public spending may shift to focus on immediate recovery needs, at the expense of investments that could otherwise promote long-run health.

“Some solutions might be as simple as communicating to families and governments that, a few years after you allocate money for recovery, maybe you want to think about additional savings for healthcare-related expenses, particularly for the elderly, communities of color, and mothers or expectant mothers,” Young said.

This article was first published by Stanford University.