Shock, insecurity and endless war: How 9/11 changed America and the world

For tens of millions of Americans alive on Sept. 11, 2001, the images are indelible: Flames exploding from a tower of the World Trade Center against a brilliant blue sky. A tsunami of smoke and debris roiling through the canyons of Lower Manhattan. Office workers — those who managed to escape — covered in grey dust.

In the shock that followed those terror attacks, it was common to imagine that the world had changed forever. Just how, exactly, no one could know. Twenty years later, after so many other turns of history, the ragged withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan is a reminder of how the nation has struggled to answer the attacks.

“One of the most lasting impacts has been the damage to the American psyche,” said Janet Napolitano, former secretary of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and former president of the University of California. “Even after Pearl Harbor, there was a presumption that we were somehow immune from attack, that our airliners would not be weaponized and flown into iconic buildings. That sort of presumption was effectively destroyed by 9/11 — and it hasn’t come back.”

Even as Americans grappled with trauma and anger at home, the attacks cleared the way for a foreign policy based on the belief that the United States can “transform foreign societies in its own self-image,” said UC Berkeley historian Daniel Sargent. This was “hubris,” Sargent said, with the “consequence of exploding the credibility of America as a superpower.”

To be sure, the American reaction to Sept. 11 achieved a critical aim: After a massive mobilization of resources, intelligence and military power, the U.S. has prevented any other large-scale attack on domestic targets. Osama bin Laden, the 9/11 mastermind, was found and killed. The war in Iraq, though ill-conceived and fatally mismanaged, removed Saddam Hussein, a vicious tyrant, from power. A generation of women and girls in Afghanistan found that with the Taliban banished, there was space for education, for work and for pursuing dreams.

In a series of interviews, Berkeley scholars said the shock and the national response set off a cascade of repercussions — misguided and expensive wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, a rise in anti-Muslim hate, and an obsessive focus on security and safety that has sometimes undermined freedom and human rights.

Asked to reflect on the 20th anniversary of the attacks, they pointed to four broad, specific examples of how 9/11 continues to shape America and the world, plus a fifth that may — or may not — come to pass.

1. Policymakers implemented aggressive plans to combat global terrorism — and to prevent “contamination” of the homeland.

In a period of major conflict, two primal fears can become pronounced, said Marika Landau-Wells, a UC Berkeley political scientist who studies how political leaders and the public perceive threats. One is fear of death. The other is fear of contamination. These fears colored the U.S. response to communism in the 1950s and to COVID-19 and illegal immigration today.

In the psychological environment that rose from the shock of 9/11, the Bush administration had support to make a dramatic response.

“They didn’t want more people to die on their watch,” said Landau-Wells. “But there was also a sense that…this ideology of international terrorism had some contaminant properties to it. It’s a little bit like communism in that respect.”

With unprecedented speed, the Bush administration transformed the national security system. Airline security was tightened and intensified. The Department of Homeland Security was created a little more than a year after the attacks, and today is the third-largest federal agency.

At the same time, U.S. foreign policy was “remilitarized,” said Berkeley political scientist George Breslauer, a scholar in U.S. foreign affairs. “After 9/11, with the neoconservatives in power, you get this notion: ‘We are the most powerful country in the world, and it’s about time to show our adversaries what that means.’”

2. Political leaders bet that terrorism could be defeated by conventional military action. This was a grave miscalculation.

Several Berkeley scholars shared a common view: The U.S. could have responded to 9/11 as if it were a crime — using law enforcement, diplomacy and intelligence along with limited military resources to hunt down Osama bin Laden, al-Qaida leaders and others linked to the attacks.

“If you want to pursue the terrorists, there are different approaches and strategies to undertake this in a legal, legitimate way rather than unleash an invasion that is going to be disastrous,” said Hatem Bazian, founder of the UC Berkeley Islamophobia Research and Documentation Project.

Added Breslauer: “Trying to fight wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, while simultaneously conducting a global police action against terror — it only brought us misery and pain.”

The death toll: Some 15,000 U.S. soldiers and military contractors died, along with some 15,000 allied military personnel. Among Afghans and Iraqis, deaths mounted into the hundreds of thousands.

The financial cost: By one estimate, the U.S. has spent more than $8 trillion — much of it borrowed — in wars launched after 9/11.

In Vietnam, the U.S. learned through failure that “conventional military deterrence…doesn’t work against insurgencies in guerilla war contexts,” Breslauer said. By repeating that approach against Afghanistan and Iraq, the U.S. “affirmed that it had unlearned the lessons of Vietnam — and that was triggered by 9/11.”

3. The attacks provoked a wave of anti-Muslim bias, harassment and violence. This demonization has become a persistent feature of our politics.

In the immediate aftermath of the terrorist attacks, society focused indiscriminate rage on Muslims, several scholars said.

“To tar a whole group of people with that brush is a big move, but I think 9/11 gave permission to think that way,” said Landau-Wells. “There was a tolerance for a kind of thinking that probably would have been frowned upon on Sept. 9th or 10th.”

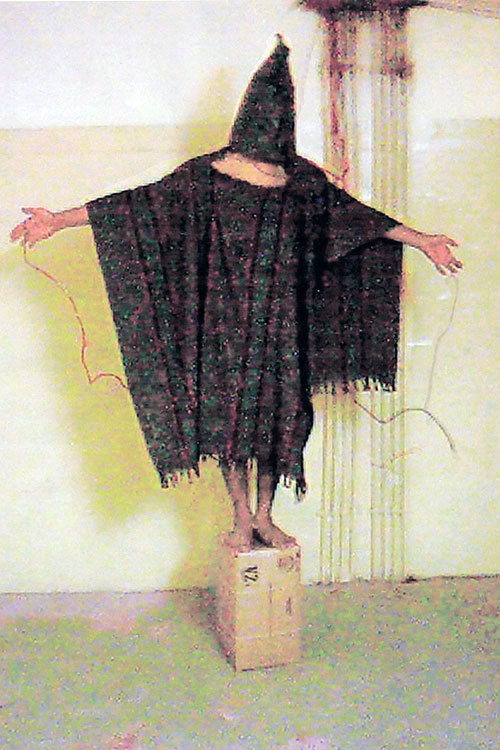

Hate crimes against Muslims, or those mistaken for Muslims, soared. Law enforcement agencies detained thousands of men who were Middle Eastern and South Asian. Agents infiltrated Arab American communities. In Iraq and in the Guantanamo Bay detention center, the images of U.S. military personnel abusing and torturing Muslim men suggested that Muslims had been officially dehumanized.

While some Americans recoiled, others did not. In a climate of suspicion and fear, Berkeley scholars said, hostility for Muslims became a political wedge issue.

Critics attacked a rising 2008 presidential candidate by his full name: Barack Hussein Obama. After Obama’s victory, future presidential candidate Donald Trump led a sustained conspiracy movement claiming that the victor wasn’t American, and was therefore not a legitimate president.

Later, as the Republican nominee, Trump would promote the lie that thousands of Muslims on 9/11 cheered the fall of the twin towers at the World Trade Center. And as president, he largely suspended tourism, business and academic visits from Muslim countries.

“Islamic terrorism, quote unquote, replaced communism as the great foreign enemy,” observed Lawrence Rosenthal, chair of the UC Berkeley Center for Right-Wing Studies. “And those who were not hostile to the domestic Muslim population — they could be characterized as enemies on the home front.”

4. Through strategic failures and compromised values, the United States suffered deep, long-term damage to its political and moral authority.

The stated goals in both Afghanistan and Iraq seemed straightforward: topple authoritarian governments seen as hostile and replace them with functional democratic states, and thereby make the region less hospitable to terrorists. But Iraq wasn’t even linked to terrorism. And the use of detention without trial, kidnapping and torture undermined U.S. claims to democratic virtue.

“The use of what was euphemistically called ‘enhanced interrogations,’ which most people would call torture, was really contrary to our values — and it was not effective,” said Napolitano, now director of the Center for Security in Politics at Berkeley’s Goldman School of Public Policy. “Those kinds of decisions not only change our self-perception, but change the perception of the United States in the world.”

The invasion of Iraq “completely torpedoed and collapsed U.S. standing” in the Muslim countries and much of the world, said Bazian. “U.S. power has diminished tremendously in the most important powers — the power of persuasion.

“Once the Abu Ghraib pictures came out, the Abu Ghraib torture, the United States’ claim that it represents the civilized world, the rule of law — at that point, the emperor had no clothes.”

5. Can the U.S. accept the humbling lessons of 9/11? Time will tell.

The world has transformed in the two decades since the terror attacks on New York and Washington, D.C. The United States is no longer the world’s sole superpower; China is a rival, and Russia remains a global force. India and other nations once considered poor and powerless are building strength.

The U.S. remains the world’s most powerful country, Breslauer said, but it cannot impose its will on the world. It must define its vital interests realistically, and then work with other powers to address global issues through diplomacy and cooperation.

“We have to search for a way to get the United States, Europe, Russia and China to collaborate on issues that all of them define as major threats,” he proposed. “Those issues can be global terror, or the avoidance of accidental nuclear launches. It can be pandemic control, or climate change. There are any number of issues on which those four entities — plus Japan and a few others — have a common stake in avoiding the worst outcomes.”

Bazian finds cause for optimism in the European fishing crews that have rescued refugees fleeing war and persecution, and in the church groups working to resettle refugees in the United States. But he sees that the U.S. military web still circles the globe, and he wonders whether the lesson has been learned.

In this new world, he and others suggested, hubris is no longer viable. Diplomacy, subtlety, cooperation — these are essential if the U.S. is to recover from the self-inflicted damage of 9/11.

“I think over time we can recover,” Napolitano said. “But we can only do it by action, by exhibiting to the world our values and how we practice them… You know, the world is a complex place, and we need to approach its complexity with a degree of humility.”