The secret language of microbes

Fungi communicate by chemical signals only, but they, like humans, appear to use different dialects.

This discovery came from a UC Berkeley study of the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa, a red bread mold that has been studied in the laboratory for nearly 100 years.

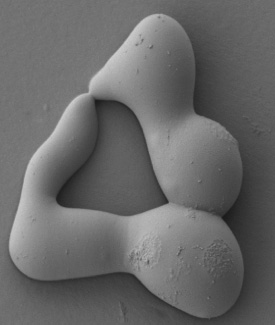

Many fungi, including N. crassa, grow as filaments or hyphae that often fuse to form an interconnected network. Hyphal networks have been shown to be important to many fungi, including the mycorrhizal fungi that form associations with plant roots, sharing nutrients.

Senior author N. Louise Glass, a professor of plant and microbial biology, said that the finding could help scientists understand how fungi communicate and cooperate for destructive purposes, such as plant diseases and animal mycoses, as well as beneficial purposes, such as symbiotic associations with plants.

“Our findings reveal a heretofore underappreciated complexity in fungal communication,” Glass said. “We have only scratched the surface on communication and interactions of these enigmatic organisms.”

Glass and postdoctoral fellow Jens Heller study communication in fungi — in particular, how they recognize their own kind. To fungi, their own kind don’t necessarily include their nearest relatives, but rather fungi with whom they share one or more genes.

Germinated asexual spores – called germlings – ofN. crassa engage in chemical conversation with one another to discriminate between different kinds, and eventually move toward and fuse with those of their own kind.

“These genetically identical cells undergo a dialogue, alternately ‘listening’ and ‘speaking,’ which is essential for chemotropic interactions,” Glass said, referring to movement toward the source of a chemical.

In the study, the researchers examined how genetically different germlings communicated and discovered, surprisingly, that N. crassa populations fall into discrete communication groups, akin to dialects.

“It seems like all strains speak the same basic fungal language, but due to different dialects, some strains cannot understand each other, and therefore are unable to establish communication necessary for cell fusion,” Heller said.

They tracked down the genes involved in distinguishing self from non-self – what some have called “greenbeard genes” because they make the organism stand out from its fellows – revealing a new mechanism by which microbes distinguish one another by actively “searching” for their own type.

The new study was published April 14 in the open-access journal PLOS Biology. For more information, read the PLOS press release.