Remembering the history of polio can help in finding a coronavirus vaccine

On a spring morning in 1955, a pair of press officers greeted a mob of reporters in a stately hall on the University of Michigan campus. The officers had hot news: A clinical trial of the long-awaited polio vaccine had proved it to be safe and effective. The reporters nearly rioted in their scramble to spread the word. Once they did, church bells rang, and people ran into the streets to cheer.

In the midst of our current pandemic, collective hope for a vaccine is just as palpable and regularly reinforced — as it was with this week’s news of promising results from a small coronavirus vaccine test. The federal government’s top infectious-disease expert, Dr. Anthony Fauci, said that “the ultimate game changer in this will be a vaccine.” President Trump assured us that a vaccine is not far off. Television hosts and pundits claim that this goal is within reach because we’ve beaten infectious killers, such as polio, with vaccines in the past.

But America’s experience with polio should give us pause, not hope. The first effective polio vaccine followed decades of research and testing. Once fully tested, it was approved with record speed. Then there were life-threatening manufacturing problems. Distribution problems followed. Political fights broke out. After several years, enough Americans were vaccinated that cases plummeted — but they persisted in poor communities for over a decade. Polio’s full story should make us wary of promises that we will soon have the coronavirus under control with a vaccine.

The first polio epidemic in the United States hit Vermont in 1894, killing 18 and leaving 58 permanently paralyzed. It was only the beginning. Over the next several decades, warm-weather outbreaks became common, striking communities one year and sparing them the next, sometimes only to return later with added force. A New York City outbreak killed more than 100 people in 1907. In 1916, polio returned and killed 6,000. The disease primarily struck children. It could kill up to 25 percent of the stricken. And it left many paralyzed, consigning some to life in an iron lung.

Scientists knew polio was caused by a virus but did not know how it spread. (We know now that it was spread by consumption of food or water contaminated by the virus in fecal matter.) Then, as now, the only way to stay safe was not to be infected. Towns with cases closed movie theaters, pools, amusement parks and summer camps. They canceled long-planned fairs and festivals. Parents kept children close to home. Those who could afford to do so fled to the country. Still, cases mounted. Among three early polio vaccines developed in the 1930s, two proved ineffective, another deadly.

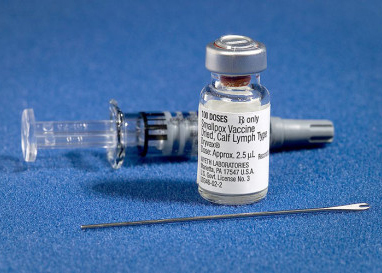

Finally, in April 1954, a promising vaccine, developed by Jonas Salk’s laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh, entered a large, yearlong clinical trial. On the day in 1955 when the press officers greeted the reporters in Ann Arbor, they shared the results: The vaccine, containing inactivated polio virus, was safe. It was also 80 percent to 90 percent effective in preventing polio.

The federal government licensed the vaccine within hours. Manufacturers hastened into production. A foundation promised to buy the first $9 million worth and provide it to the nation’s first and second graders. A national campaign got underway.

But less than a month later, the effort ground to a halt. Officials reported six polio cases linked to a vaccine manufactured by Cutter Laboratories in Berkeley, Calif. The surgeon general asked Cutter to recall its lots. The National Institutes of Health asked all manufacturers to suspend production until they met new safety standards. Federal investigators found that Cutter had failed to completely kill the virus in some vaccine batches. The flawed vaccines caused more than 200 polio cases and 11 deaths.

The vaccine program partly restarted two months later, but more mayhem followed. With the vaccine in short supply, rumors spread of black markets and unscrupulous doctors charging exorbitant fees. One vaccine manufacturer planned to vaccinate its employees’ children first, and then sent a letter to shareholders promising their children and grandchildren priority access, too.

States asked the federal government to create a program to ensure fair distribution. A Senate bill proposed making the vaccine free to all minors. A House bill proposed free vaccines only for children in need; according to newspaper accounts from the time, discussion of the bill triggered an “angry row” that forced the speaker to call a “cooling off” recess. The $30 million Polio Vaccination Assistance Act that President Dwight Eisenhower signed that August was a compromise that essentially let states decide for themselves.

Polio cases fell sharply over the next few years. Then in 1958, as national attention began to flag, cases ticked back up — among the unvaccinated. Polio cases clustered in urban areas, largely among poor people of color with limited health care access. States’ “pattern of polio,” government epidemiologists noted, had become “quite different from that generally seen in the past.”

Three years later, the federal government approved an oral polio vaccine, developed by Albert Sabin’s laboratory in Cincinnati, containing weakened, not inactivated, virus. By the end of that year, polio infections were down 90 percent from 1955 levels. In 1979, the country recorded its last community-transmitted case.

Today, decades into a global vaccination campaign, polio persists in just three countries. The battle against the disease has been a century-long march. And it has required a sustained commitment to continuing polio vaccination — a commitment now compromised as global polio vaccination efforts have been put on hold to slow the coronavirus’s spread.

Granted, there are countless differences between the fight against the coronavirus and the long-ago fight against polio. The global capacity for vaccine research and development is far greater than it was in the 1950s. Drug approval and manufacturing safety protocols have been refined since then, too. Already, just months into the current pandemic, there are far more vaccines in development against the coronavirus than there ever were against polio.

But the regulatory thresholds we’ve spent decades putting into place are being swept aside to speed that development. And some of the coronavirus vaccines now in “lightning fast” development — by new biotech firms, university labs and familiar pharmaceutical giants — are as novel as the first polio vaccine was in 1955.

If one does prove safe and effective, we will face the same challenges we faced then — of making enough to protect the population, without causing harm, and distributing it without exacerbating existing inequities in our society.

This story was originally published in The New York Times on May 20, 2020, and was co-authored by Elena Conis, professor in the Graduate School of Journalism at UC Berkeley, Michael McCoyd, a Berkeley doctoral candidate in computer science, and Jessie A. Moravek, who is also a Berkeley doctoral student in environmental science, policy and management.