QB3 symposium highlights job creation through innovation

Ten years ago, then Gov. Gray Davis outlined a plan to use research generated on the UC campuses to drive innovation and economic vitality in California. Flush with cash from the dot-com boom, Davis launched a $1.2 billion public-private effort to create an enterprise that he called a “down-payment on the future.”

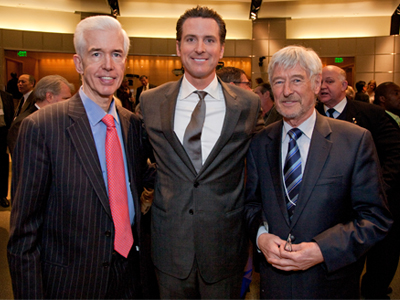

The successes of that vision and investment were celebrated as a roadmap for California’s future on Wednesday, during a symposium hosted by the California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences (QB3) at Mission Bay and headlined by Davis, now a Distinguished Policy Fellow at the UCLA School of Public Affairs.

“The government had plenty of money and I wanted to invest some of that money in what we do best in California, which is innovation,” Davis said of the initial goal, calling innovation the single most important reason California is a major influence worldwide.

“If you’re born in the east, you grow up and you want to join something,” Davis said. “If you’re born in California, you grow up and you want to start something.”

As a result, QB3 and its three sister “Institutes for Science and Innovation” were created with the three-fold missions of supporting a specific sector of technology, fostering economic growth, and using those efforts to benefit society.

QB3, which includes researchers at UC Berkeley, UCSF and UC Santa Cruz, focuses on the junction between the biological and quantitative sciences. Davis said that the institute, headquartered at the UCSF Mission Bay campus and led by Regis Kelly, PhD, has exceeded his goals “many times over.”

That includes supporting world-class research with clear benefits to society, such as using yeast to grow low-cost anti-malarial drugs, or engineering bacteria to make biofuels, or developing technology to identify how aggressively tumors are growing. QB3 also has held true to its mission of driving economic development and fostering entrepreneurship through a seed-stage venture fund, an incubator network to provide the Silicon Valley-style “garage” and multiple services for entrepreneurs.

“Innovation, for us, comes in trying to connect things that have never been connected before,” said Kelly, director of QB3. That applies to scientists collaborating outside their fields, as well as QB3’s efforts to bring industry and academia together to help move great ideas out of the lab and into commercial use.

California Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom, who served as mayor of San Francisco from 2004 to January 2011, said those efforts – along with city changes such as waving the payroll tax for biotech companies and changing parking allocations – have been key in transforming San Francisco into a life sciences center. Once the home of one biotechnology company, San Francisco now is a national biotech hub with 74 bioscience companies, including 44 that have spawned from the QB3 Mission Bay Incubator Network.

Those are lessons he hopes to apply statewide, Newsom said, but it won’t be easy.

“If you think it was bad in 2003 in San Francisco, trust me, it’s exponentially worse in Sacramento,” said Newsom, noting that without a state economic plan or clear vision for fostering innovation, the state will be overshadowed by significant efforts in states like Massachusetts. “We have got to get our act together in California.”

Newsom’s concerns were substantiated by Christie Smith, a principal with Deloitte Consulting LLP, who gave the funding figures behind that fierce competition: a $3 billion innovation investment in Texas; $1.6 billion in Ohio; and $1 billion in Massachusetts. By comparison, California now has piecemeal efforts such as these institutes, but no continued investment to compare with the other states.

The winning formula, she said, is to have governments, universities, investors and established companies come together, with sustained investments and a broad focus on generating innovation.

During an economic crunch, that might seem like something that would be nice to think about when the state is prosperous again. But that might be too late.

“Whenever there’s a tremendous change in the environment, those species that will survive are those that were innovative, biologically, in advance,” Kelly said. The same applies to society. “If we don’t learn to innovate as a society, it’s not clear that we will survive.”