Ph.D. student turns recycled plastic into face shields for Ugandan medics

In 2016, Paige Balcom fell in love with Uganda. It happened in Lukodi, a village outside of the town of Gulu, where she was on a Fulbright research grant. Working with farmers and a school for child mothers, she tested whether aquaponics — in this case, raising fish and using their nutrient-rich water to fertilize vegetable plants, which purified water for the fish — could be successful there.

Balcom’s biggest find, though, were the deep friendships she made with the school’s teachers and students, many of them victims of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a Ugandan rebel group led by Joseph Kony, that, starting in 1987, waged a violent, nearly 20-year campaign against the Ugandan government. An LRA hallmark was abducting children and forcing them to work as child soldiers, porters and “wives,” or sex slaves, to LRA fighters.

“Engineers are usually logical, not emotional, but I cried more than I’d ever cried as I left the village for home,” said Balcom, who a month later became a Ph.D. student in mechanical engineering at UC Berkeley. “I’d learned a lot about the culture and history and richness of Uganda, and felt the warmth of the people, and heard what they’d lived through, and it really hit me hard. It made me want to help.”

Now in her third year of graduate school, Balcom is back in Uganda where, this past January, she launched Takataka Plastics, a social enterprise in Gulu that is recycling some of the country’s abundant plastic waste — Uganda generates 600 metric tons a day; up to 50% isn’t collected there, and in Gulu, it’s 80% — into affordable construction materials, primarily wall tiles. (Takataka means “waste” in Swahili). The organization, with a team of five full-time staffers, also employs and provides a healing workplace for local youth suffering from trauma, exploitation and human trafficking.

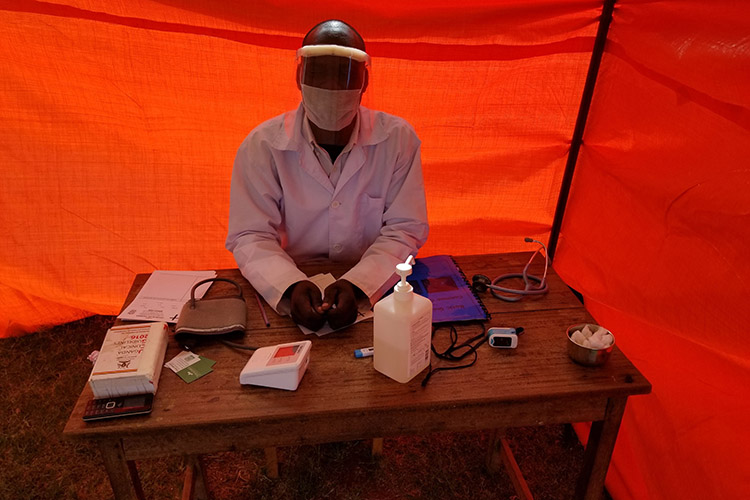

Today, as COVID-19 spreads in Africa, Balcom and her Takataka Plastics cofounder, Peter Okwoko, a Ugandan environmental and community activist, are beginning to produce an inexpensive and more urgently-needed product from recycled plastic — face shields for Gulu’s medical workers.

“The hospitals are woefully underequipped. Most have no face shields for their staff,” said Balcom. “The main government hospital has one oxygen bed, which doesn’t even work. It has virtually no personal protective equipment; an N95 respirator is unheard of. One bar of soap is supposed to be used to clean an entire ward for a week.”

As of this week, she added, “Uganda has 53 official cases of COVID-19, but there are probably more because of insufficient testing capabilities.”

UC Berkeley student Paige Balcom talks about her work in Uganda. (Video by Roxanne Makasdjian)

Okwoko and Balcom investigated face shields on the market and, with one of Takataka Plastic’s two engineers, made a prototype by hand from recycled plastic. It took three days to develop samples to take to a local clinic for testing. “The doctor had the staff wear the prototype for a day and give us feedback,” said Balcom. “They really liked it, and one said, ‘I don’t even feel like taking it off.’”

After another three days, they’d adjusted the shape of the clear shield, which completely covers the face, widening it to get rid of the glare some wearers experienced. When handmade, the face shield costs 80 cents, but with orders coming in from local hospitals — there’s one public hospital and several private ones in Gulu — Balcom and Okwoko have ordered machinery capable of manufacturing 400 a day at a cost of just 25 cents each.

“The government health facilities have no budget for face shields, no capacity to buy them,” said Balcom. “So, we’ve set up a GoFundMe campaign to cover those costs. We hope to make the shields in time to fight COVID-19 in Uganda and have the flexibility to make other medical parts, if needed.”

That work that can be done with the injection machine on its way from Austria — it heats shredded flakes of plastic waste, without releasing toxic fumes, and injects the melted plastic into a mold, to shape it into the desired product — will allow Takataka Plastics initially to employ eight homeless youths, who will receive free food and shelter at the space that Takataka Plastics uses without charge from Elephante Commons, a community center in Gulu.

The organization is funded primarily by grants, including from UC Berkeley’s 2018 Big Ideas competition and the 2019 Scaling Up Big Ideas contest, and from personal donations.

When Takataka Plastics is in full production mode — Balcom and Okwoko also hope to purchase a shredding machine, “to smooth the production process and ensure a steady stream of material,” said Balcom — they plan to hire 30 young people, full time.

“There are about 400 youths living and working on the streets of Gulu. The average age is 17,” said Balcom. “Their biggest struggle now, with the coronavirus, is the curfew at night. Since they have nowhere to sleep, they have to constantly be dodging police.”

Uganda currently is under lockdown to enforce safety measures to control the spread of the virus. All borders are closed, movement within the country is restricted, schools and non-essential shops are closed and a strict 7 p.m. curfew is being enforced.

“Everyone has to be in their homes, or the police will come and cane you,” said Okwoko. “It’s a serious beating. Most people fear the beating more than COVID-19.”

The homeless also have no access to “hand-washing, masks or other sanitation measures,” said Balcom. “And most Ugandans live hand-to-mouth, using the money they earn each day for food.” With the arrival of COVID-19, and with businesses closed, she added, “people are going hungry.”

What’s more, said Balcom, many Ugandans don’t understand what causes COVID-19, since many have no access to the internet. “There’s a lot of misinformation about what the symptoms are, how they can protect themselves properly, who can really transmit the disease and when they should go to a health clinic,” she said. “It’s really sad.”

Vibrance and pain in Gulu

Balcom first went to Uganda as an undergraduate at the University of New Hampshire. She was part of Engineers Without Borders, and as a sophomore, she joined a two-week clean water project in a village outside Gulu. “I really loved the experience,” she said, “but I knew that two weeks wasn’t long enough to really understand what life was like for people in Uganda.”

She described Gulu as vibrant and bustling, where people wear colorful, traditional kitenge — patterned African fabric used for making clothes, wrapping around women’s waists or for carrying a baby — and music blares from speakers at street shops.

“People are super-friendly and call out greetings, or shake hands,” she said. “Street vendors are selling fruits and vegetables in the market, girls are walking with bananas or fried bread they made in baskets on their heads, old mamas are selling popcorn outside church and young men are making Rolex (fried egg wrapped in chapati) at small roadside stands under umbrellas.”

with the prototype shredding machine he worked on in May 2019. (Photo by Paige Balcom)

But underneath the liveliness, said Balcom, “remain a lot of scars from the war. People are traumatized and haven’t received counseling to process everything that happened to them.”

Kony was indicted for war crimes and crimes against humanity in 2005 and is wanted by the International Criminal Court, but has evaded capture. U.S. and Ugandan troops called off their mission to find him in 2017.

Some of the homeless youth in Gulu today were born in captivity to girls kidnapped by LRA rebels. Because of this, it’s not unusual for them, and their mothers, to have been rejected or stigmatized by relatives, neighbors and peers. Other young people in Gulu are adrift after fleeing abusive home environments.

“The population of Uganda is super-young, because many in the middle generation died in the war,” said Balcom. “A whole generation lost out on education and on learning traditions from their elders. The young now lack good role models.”

Some of girls currently at ChildVoice International, the school where Balcom worked in 2016, were born in captivity and then lived in IDP (international displaced person) camps, “which was a whole other struggle for survival,” she said. They depended on aid for food, she explained, and with no doors on the shelters, they were assaulted.

Plans to expand, but face shields first

When Balcom began graduate school in fall 2017, she wanted to help solve problems affecting her new Ugandan friends, so she started researching plastic waste. She spent three months in Uganda conducting an assessment of plastic waste and interviewing more than 200 people. (Her Ph.D. research is focused on heat transfer and is somewhat related to her work with Takataka Plastics. It involves exergy analyses to quantify the environmental and resource costs of different methods of disposing of plastic waste, as it applies to the developing country context of Uganda).

She also met Okwoko, a graduate of the Innovative Communication Technologies and Entrepreneurship program at Aalborg University in Denmark. He founded AfriGreen Sustain, a waste management social enterprise in Gulu, and he co-founded Hashtag Gulu, a community-based organization that helps homeless youth.

Okwoko said Ugandans “tend to use a lot of plastics, mostly water and soda bottles, on a daily basis. There are laws about plastics — a few directives ban the use of plastic bags — but enforcement is lacking.” As a result, the waste piles up in dumps and landfills, gets buried on people’s property and often is burned, resulting in the release of harmful carcinogens and greenhouse gases, especially when the plastic is made of polyethylene terephthalate (PET).

The nearest recycling plant is six hours away in Kampala, Uganda’s capital, and “transporting empty bottles that far doesn’t make sense,” said Balcom. “Uganda also is desperate for a solution to (products made of) PET, which is difficult to process. Machines to turn (PET plastic) into new bottles or fibers for clothes or carpets are super-expensive, so Uganda is stuck.”

So, in 2019, Balcom and Okwoko opened in Gulu a small plastic collection center, built prototype machines and began making recycled plastic wall tiles that are available in custom colors and shapes for use in people’s homes.

“We can sell them more cheaply than the cost of ceramic tiles, which can break and chip,” said Balcom. “Ours are rigid, but lightweight, and you just need glue to attach them. We sell them to hardware shops and contractors.”

The tiles are increasingly popular as Gulu rapidly grows into a city; it’s expected to get that designation in July. When Balcom first arrived there in 2014, the main road from Kampala to Gulu was “partially a dirt road, and the market was makeshift stalls of branches and grass. Now, the main market building is the centerpiece of the town,” and last year, all of Gulu’s roads were surfaced with tarmac.

“Construction in Gulu is booming,” said Okwoko. “People are excited about that, and the fact that we’re making tiles from recycled materials makes them say, ‘Wow! You’re making this from waste?’”

In the coming year, Balcom and Okwoko plan for Takataka Plastics to become a full-scale plastic processing operation that is financially self-sustaining from the sale of tiles, to add more jobs and to create a cleaner, healthier environment in Gulu. They also hope to raise $70,000 to build bigger machines that can process half of Gulu’s plastic waste— approximately 9 metric tons a month — and to expand their product line.

Ultimately, Balcom said, she and Okwoko to expand Takataka Plastics to five more Ugandan towns and eventually to other developing countries.

But for now, producing face shields is the top priority. Said Balcom,“The faster we get rid of COVID-19, the better.”