Performance Spaces Still Struggle With ‘Soft Censorship’

From the U.S.’s first Black theater in New York to today's Broadway stages, there’s been “a kind of de facto censorship” of diverse stories throughout the country's history, says Professor Shannon Steen.

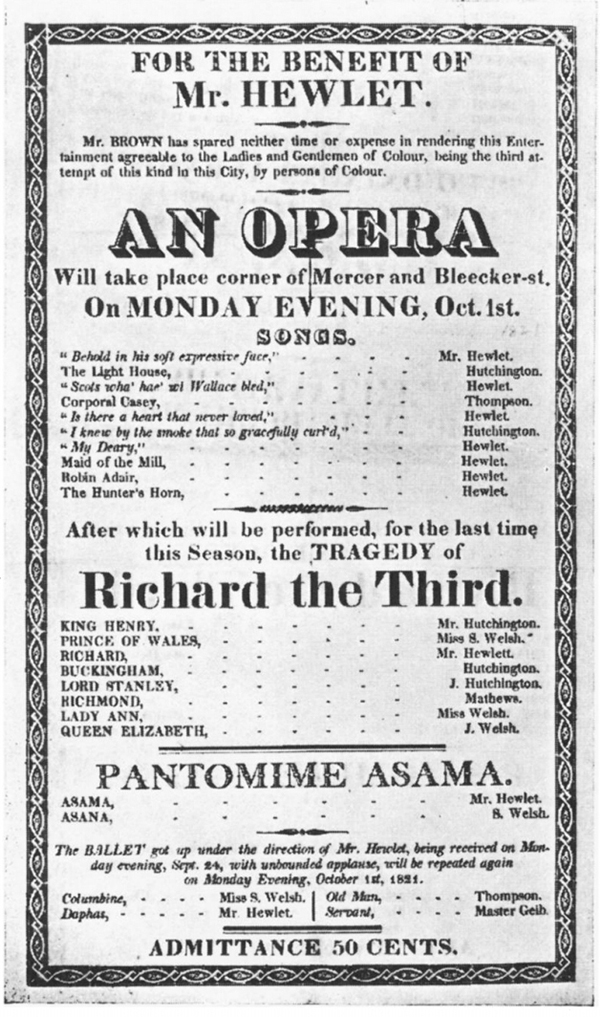

In 1821, two free Black men from the West Indies — playwright William Alexander Brown and actor James Hewlett — opened what’s considered the United States’ first Black theater in New York City.

At the African Grove Theatre, as it was known, Black performers put on classical pieces, like Shakespeare’s Richard III and Othello, as well as ballets, operas, comedies and Brown’s original plays. Its audiences were racially integrated, but most often were made up of Black patrons, both free and enslaved. (In 1799, the New York Legislature passed a law to gradually end slavery, but full emancipation didn’t happen until 1827.)

When white attendees came to the shows, they were often hostile, harassing the actors and rioting until the performances couldn’t go on. When police came to the scene, instead of arresting the white rioters, they arrested the Black performers.

“This is just one example of a long history of performers from vulnerable or excluded communities having their events shut down in this way,” said Shannon Steen, a UC Berkeley professor of theater, dance and performance studies and of American studies.

Recent history might suggest that much progress has been made, in terms of diversity, on the stages of American theater. In 2002, Suzan-Lori Parks’ Topdog/Underdog won a Pulitzer Prize for Drama — the first time a Black American woman won in the category — and the revival of her play in 2023 earned her a Tony Award and an Outer Critics Circle Award. After the musical Hamilton, written by Lin-Manuel Miranda and performed by a cast of mostly non-white actors, opened on Broadway in 2015, it also won a Pulitzer Prize, as well as 11 Tony Awards. But a closer examination of the theater industry reveals how far it has yet to go.

Steen’s research includes the history of popular performance in U.S. history, and she’s the author of the 2010 book Racial Geometries: The Black Atlantic, Asian Pacific, and American Theatre. What’s become clear in her work is that “soft censorship” — when ideas or content are indirectly curtailed, in effect muting or limiting the circulation of certain stories or ideas — remains pervasive on American stages. Unlike hard censorship, like when a performance is banned by a government, this more insidious form of artistic oppression is subtler and requires more complex approaches to create sustainably diverse storytelling in American theater.

Data reflect evidence of soft censorship in the lack of diverse programming in U.S. theaters. The Asian American Performers Action Coalition found that in the 2018-2019 season, about only 11% of shows produced on Broadway were by playwrights of color. For nonprofit theaters in New York City, the number was a little higher, at just over 20%.

“That tells you a lot about the systems of representation,” said Steen. “While it’s not hard state control, and there isn’t a law limiting writers of color, it’s a kind of de facto censorship of certain kinds of stories.”

Broadway, for example, is seen as the most iconographic of American theatrical spaces. It has a “metonymic relationship” with the U.S., she said, standing in as a sort of representative for the country as a whole. So when plays on Broadway don’t have a broad sense of representation, it distorts Americans’ sense of the country and the communities within it. And it influences what kinds of stories other theaters across the country and the world bring to their performance spaces.

Since the 2020 murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter protests that followed, Steen said, there’s been a growing effort by theaters to produce more shows by writers of color, like the 2023 Tony Award-winning play Appropriate by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, and Hell’s Kitchen, a semi-autobiographical musical by 15-Grammy Award winner Alicia Keys in the same year. But there are persistent constraints that have made it difficult to bring audiences to an expanded lineup of shows.

A big barrier is financial: Theaters need to make money to stay open, but the models that many of them are using aren’t working well.

To attend a Broadway show is too costly for many would-be theatergoers, especially from marginalized communities. Regional and nonprofit theaters, which typically rely on member subscriptions and support from the National Endowment for the Arts, are at the whim of what their largely white suburban audiences want to see. If their audiences cancel their memberships because, say, they don’t like the latest slate of plays by writers of color, then those theaters lose a significant part of their revenue stream, Steen said. Theaters are also struggling, even on Broadway, to rebuild their audiences after a drastic drop during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the 2019 book America in the Round, UC Riverside Professor Donatella Galella chronicles the ups and downs of Washington, D.C.’s Arena Stage, a celebrated professional regional theater dedicated to American plays and playwrights. The first theater in the nation’s capital to welcome a racially integrated audience when it opened in 1950, it’s known for its long history of support for Black actors and playwrights, like James Earl Jones and Zora Neale Hurston.

Even so, Arena Stage has struggled throughout its history to build diversity in its program, Galella wrote. When its artistic director produced the 1992-93 season, in which one-quarter of the plays were by Black authors, and some canonical work by white authors had multiracial casts, the theater lost a significant number of subscribers. Later, when the theater ran focus groups to figure out why, what they learned was disturbing.

Some former subscribers said they found multiracial casting “disconcerting,” “distracting” and “contrived,” Galella wrote. Others said they wanted to separate art from social justice. They said they resented what appeared to be a prioritizing of Black patrons over white patrons. Some were more explicit in their support of white supremacy, with one person writing on a subscription brochure that there “was hardly a white person anywhere. No wonder everyone we know has stopped going to Arena.”

“It’s just really shocking, the kinds of anger and hostility that was unleashed by their subscriber base to do even this kind of modest expansion for writers of color,” said Steen.

Even though it happened more than 30 years ago, added Steen, the “dynamics and sentiments Gallela described were active in the theater until quite recently — and perhaps still are.” Until the late 2000s, Steen noted that regional theaters had avoided heavily diversifying their slates of playwrights, largely out of fear that subscribers would respond as they did at Arena Stage in the early ‘90s.

Steen said that while we generally think of this predicament as an economic problem, the larger impact is a muting of the voices of writers of color. “We don’t ordinarily conceive of that as a censorship problem — there’s no government agency preventing theaters from producing writers of color — but it enacts similar effects,” she said.

While Berkeley’s Department of Theater, Dance and Performance Studies doesn’t rely on the same subscription models as most American theaters, it’s dedicated to shifting the narrative and decentering whiteness in its curriculum. In fall 2020, instructors in the department committed to having at least 60% of the material they teach be created by people of color. They’ve even compiled a canon of works as a resource that professors and instructors can pull from as part of their curricula.

This curriculum shift has paid off, said chair and professor SanSan Kwan, who joined the department in 2011 and has since witnessed its evolution over the past 13 years.

“The initiative gave us the opportunity to rethink some of the presumptions that were built into our syllabi regarding canons and how we historicize,” said Kwan. “It has asked us to consider the ways that some of the key theories we teach in performance studies can be introduced via normally overlooked thinkers from the global majority, instead of via the usual Euro-American suspects.”

Over the past four years, 10 of 16 plays the department produced were by playwrights of color, including the coming-of-age story In the Red and Brown Water by Tarell Alvin McCraney; the Brazilian folktale The River Bride by Marisela Treviño Orta; and the Berkeley student-devised piece The After Party. And within the last year, the department has hired two theater professors — Timmia Hearn DeRoy and Karina Gutiérrez — who focus on social justice theater and the intersection of politics in performance.

So what can theaters across the U.S. do to survive financially, while expanding the types of stories they’re presenting and bringing in a broader, more diverse audience?

“That’s what everyone is trying to figure out right now,” said Steen.

There are all sorts of strategies that theaters have started to explore in the last few years, she said. They include finding new ways to reach a broader swath of potential theatergoers, like through community engagement events and by presenting bilingual productions. Theaters have also provided incentives that include lowering ticket prices for specific communities that have historically been excluded from the venues, like by using a sliding scale and offering flexible subscriptions.

Even seemingly minor aspects of the theatergoing experience can help create a more welcoming atmosphere for all; for example, ushers can act more like greeters at a church and welcome patrons, instead of guarding the doors, as is common practice at many theaters. At institutions like the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco, a page explicitly tells patrons what the “house rules of play” are, aiming to undo stereotypes that theatergoers must be passive and reserved.

“The question is, how long will they be willing to keep trying these efforts if the payoff isn’t fast enough?” Steen said.

Throughout history, theater has been an important medium to challenge society’s norms and to push all of us to think about which forms of expression are “acceptable,” both in content and form. It’s a never-ending project, said Steen — one that she hopes theaters will continue to work on, building robust spaces of experimentation and the freedom to tell stories that have been kept from America’s stages for far too long.