New CRISPR-powered device detects genetic mutations in minutes

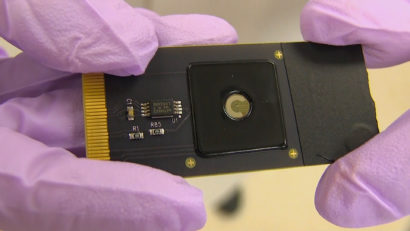

A team of engineers at the UC Berkeley and the Keck Graduate Institute (KGI) of The Claremont Colleges combined CRISPR with electronic transistors made from graphene to create a new hand-held device that can detect specific genetic mutations in a matter of minutes.

The device, dubbed CRISPR-Chip, could be used to rapidly diagnose genetic diseases or to evaluate the accuracy of gene-editing techniques. The team used the device to identify genetic mutations in DNA samples from Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients.

“We have developed the first transistor that uses CRISPR to search your genome for potential mutations,” said Kiana Aran, an assistant professor at KGI who conceived of the technology while a postdoctoral scholar in UC Berkeley bioengineering professor Irina Conboy’s lab. “You just put your purified DNA sample on the chip, allow CRISPR to do the search and the graphene transistor reports the result of this search in minutes.”

Aran, who developed this technology and brought it to fruition at KGI, is the senior author of a paper describing the device that appears online March 25 in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Doctors and geneticists can now sequence DNA to pinpoint genetic mutations underlying a host of traits and conditions, and companies like 23andMe and AncestryDNA even make these tests available to curious consumers.

But unlike most forms of genetic testing, including recently developed CRISPR-based diagnostic techniques, CRISPR-Chip uses nanoelectronics to detect genetic mutations in DNA samples without first “amplifying” or replicating the DNA segment of interest millions of times over through a time- and equipment-intensive process called polymerase chain reaction, or PCR. This means it could be used to perform genetic testing in a doctor’s office or field work setting without having to send a sample off to a lab.

“CRISPR-Chip has the benefit that it is really point of care, it is one of the few things where you could really do it at the bedside if you had a good DNA sample,” said Niren Murthy, professor of bioengineering at UC Berkeley and co-author of the paper. “Ultimately, you just need to take a person’s cells, extract the DNA and mix it with the CRISPR-Chip and you will be able to tell if a certain DNA sequence is there or not. That could potentially lead to a true bedside assay for DNA.”

Bypassing the bottleneck

The CRISPR-Cas9 system is famous for its ability to snip threads of DNA at precise locations like a pair of razor-sharp scissors, giving researchers unprecedented gene-editing capabilities. But for the Cas9 protein to accurately cut and paste genes, it first has to locate the exact spots in the DNA that it needs to cut.

For Cas9 to find a specific location on the genome, scientists must first equip it with a snippet of “guide RNA,” a small piece of RNA whose bases are complementary to the DNA sequence of interest. The bulky protein first unzips the double-stranded DNA and scans through until it finds the sequence that matches the guide RNA, and then latches on.

To harness CRISPR’s gene-targeting ability, the researchers took a deactivated Cas9 protein — a variant of Cas9 that can find a specific location on DNA, but doesn’t cut it — and tethered it to transistors made of graphene. When the CRISPR complex finds the spot on the DNA that it is targeting, it binds to it and triggers a change in the electrical conductance of the graphene, which, in turn, changes the electrical characteristics of the transistor. These changes can be detected with a hand-held device developed by the team’s industrial collaborators.

Graphene, built of a single atomic layer of carbon, is so electrically sensitive that it can detect a DNA sequence “hit” in a full-genome sample without PCR amplification.

“Graphene’s super-sensitivity enabled us to detect the DNA searching activities of CRISPR,” Aran said. “CRISPR brought the selectivity, graphene transistors brought the sensitivity and, together, we were able to do this PCR-free or amplification-free detection.”

Aran hopes to soon “multiplex” the device, allowing doctors to plug in multiple guide RNAs at once to simultaneously detect a number of genetic mutations in minutes.

“Imagine a page with a lot of search boxes, in our case transistors, and you have your guide RNA information in these search boxes, and each of these transistors will do the search and report the result electronically,” Aran said.

Rapid Diagnostics

To demonstrate CRISPR-Chip’s sensitivity, the team used the device to detect two common genetic mutations in blood samples from Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) patients.

Conboy, co-author of the paper, says CRISPR-Chip could be an especially useful device for DMD screening, as the severe muscle-wasting disease can be caused by mutations throughout the massive dystrophin gene — one of the longest in the human genome — and spotting mutations can be costly and time-consuming using PCR-based genetic testing.

“As a practice right now, boys who have DMD are typically not screened until we know that something is wrong, and then they undergo a genetic confirmation,” said Conboy, who is also working on CRISPR-based treatments for DMD.

“With a digital device, you could design guide RNAs throughout the whole dystrophin gene, and then you could just screen the entire sequence of the gene in a matter of hours. You could screen parents, or even newborns, for the presence or absence of dystrophin mutations — and then, if the mutation is found, therapy could be started early, before the disease has actually developed,” Conboy said.

Rapid genetic testing could also be used to help doctors develop individualized treatment plans for their patients, Murthy said. For example, genetic variations make some people unresponsive to expensive blood thinners, like Plavix.

“If you have certain mutations or certain DNA sequences, that will very accurately predict how you will respond to certain drugs,” Murthy said.

Finally, because the CRISPR-Chip can be used to monitor whether CRISPR binds to specific DNA sequences, it could also be used to test the effectiveness of CRISPR-based gene-editing techniques. For example, it could be used to verify that guide RNA sequences are designed correctly, Aran said.

“Combining modern nanoelectronics with modern biology opens a new door to get access to new biological information that was not accessible before,” Aran said.

Co-authors of the paper also include Reza Haijan, Sarah Balderston, Thanhtra Tran, Mandeep Sandhu and Mitre Athaiya of the Keck Graduate Institute; Tara Deboer, Jessy Etienne and Noreen Wauford of UC Berkeley: Jolie Nokes and Brett Goldsmith of Cardea Bio; Regis Peytavi of NanoSens Innovations and Jacobo Paredes of the University of Navarra.

This work was primarily supported by Keck Start-up funding to the Aran Lab, by the Rogers Family Foundation and by an Open Philanthropy Research Gift.

RELATED INFORMATION

- Detection of unamplified target genes via CRISPR-Cas9 (Nature Biomedical Engineering)

- Aran Lab website