New Berkeley center will explore bipartisan security solutions

Social media disinformation, climate change debates, foreign interference in elections — some of the defining themes of recent American politics seem only loosely connected. But underlying the headlines is a single, troubling theme: The nation’s political process is suffering a historic level of instability.

How to deal with those complex challenges in a focused, effective way? A new initiative headed by Janet Napolitano, former UC president and U.S. Department of Homeland Security secretary, will bring Berkeley faculty, researchers and students from across disciplines into the new Center for Security in Politics.

The center, based at the Goldman School of Public Policy, is expected to work across an extraordinary range of issues — from election technology and biotechnology, to climate change and changing communication, and to psychology and artificial intelligence.

Napolitano has a unique vantage on the challenges: She has served as governor of Arizona, head of Homeland Security, president of one of the most influential university systems in the world, and today as a professor in the Goldman School. In recent months, she’s been working with other former leaders of Homeland Security, both Republicans and Democrats, to raise the visibility of issues that warrant consideration by policymakers.

To launch the center, four of these Homeland Security secretaries will appear Thursday, Feb. 4, in an online installment of Berkeley Conversations. “Homeland Security in a Post-Trump Era” will be webcast live from 11 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. PST, featuring Napolitano and Jeh Johnson, who served under President Barack Obama, along with Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Ridge and Michael Chertoff, who served under President George W. Bush.

The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Berkeley News: Let’s start with a basic question: What is meant by the concept of security in politics?

Janet Napolitano: It is an integration of academic research in areas, particularly those that are technology-based, with practical policymaking and politics. How do we blend those two better?

In order to make our political environment more secure, more trustworthy?

To make our country more secure in the end and to make our policymaking richer. We have, across the Berkeley faculty, a tremendous breadth and depth of expertise, but I’m not sure that it gets translated in a way that full use is made of it.

When we think about security and politics today, what are the big lessons that you think we should take away from 2016 and the 2020 election and its aftermath?

It’s almost too soon to identify lessons from the 2020 election. But one lesson that’s becoming increasingly clear is that we have a population that almost is living in two alternative universes at the same time. One of the things that concerns me is the lack of appreciation for science, for data and for facts by too many in our in populace.

Science, data and facts — and having a stronger voice for them in our politics and in our policymaking — that’s one of the motivations behind the center.

What are some of the other significant challenges to security for our political system and our political culture?

The center will focus on three areas. One is the security risks that emanate from climate change. Those run the gamut from more extreme weather events to the impact on our military, from phenomena like sea-level rise to the impact of climate change on human migration patterns across the world.

A second is the notion of cybersecurity and emergent technologies, quantum computing and so forth, and also biotechnologies like CRISPR. What are the risks there? What are the rules of the road?

This may not be the right word, but how do we better police the uses of these kinds of technologies? How do we better identify the risks associated with them, and how then deal with those risks? That’s a very rich area that is not yet adequately explored.

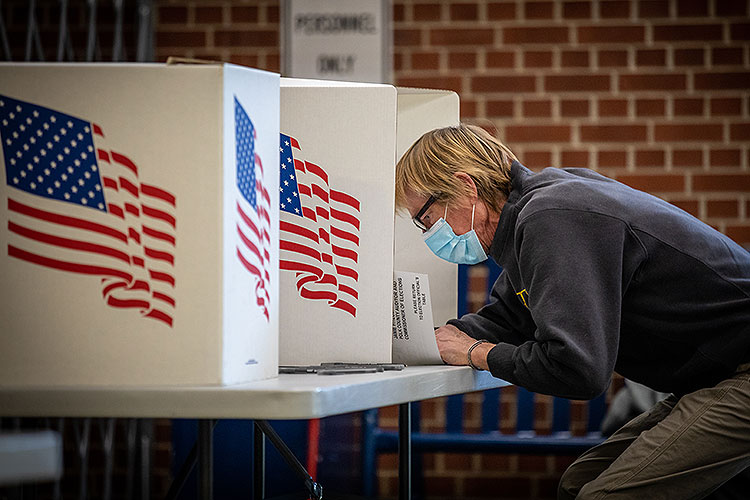

Third, a particular problem set that we’ve identified is election integrity. You know, you can’t have a functioning democracy if people don’t believe that elections are secure. We’ve seen that in spades in the aftermath of the 2020 election.

What are the best ways to conduct an election? What are the best ways to do a post-election process so that people understand that the votes they cast were accurately counted and accounted for?

That’s a particular problem that that involves technology, but also political science, journalism and so forth.

One of the areas that the center is going to focus on is the threat of foreign interference in our political environment and, of course, we’ve heard a lot about Russian interference, especially in 2016. Just recently, there’s been a massive hack of U.S. government agencies and tech companies that has been linked to Russia. Has such interference already caused damage in our political environment?

Clearly, in 2016 the Russians were all over that election. There’s no evidence that their activities affected the actual count of the ballots, but it certainly caused a lot of dissension and unrest and division in the United States in the period leading up to the election.

My understanding is that those activities continued in 2020, but they’ve been, in a way, superseded by the challenges to the counting of the ballots in the various states.

Does it seem that the U.S. has not been ready for some of these challenges that have confronted the political culture and the political environment?

It’s not so much being ready — you can’t prepare for something that you don’t anticipate. You get kind of caught by surprise, and then you fix it, you take action to address it.

None of us has a crystal ball. That’s not in our arsenal. But we do have academics, researchers, who spend their lives understanding the reach of what can happen, and the center gives us a great opportunity to better to integrate what they know and appreciate with policymaking and politics.

Can you elaborate on that? What role might the center play in addressing some of these challenges? How will the center seek to have an impact?

Several ways. We’ll seek to have an impact by sponsoring research. We’ll seek to have an impact by bringing practitioners together with academics and students to tackle the challenges emerging in our politics infrastructure, for example. And we will recruit top talent and leading officials to Berkeley to examine the key issues of the day.

Our initial event will be a discussion with four former secretaries of homeland security, and it will be followed up in March with a daylong workshop on election integrity. In that workshop, we will have participants who were really on the front lines in 2020, some secretaries of state, some state attorneys general, the head of the cyber integrity agency of the Department of Homeland Security. That will be another way that we hope to have impact.

In recent months, you’ve been working with other former Homeland Security secretaries, both Republicans and Democrats. Moving forward, how important will it be for the center to have a bipartisan orientation, to look at issues through a bipartisan lens?

Well, I think that’s very important, and that’s why our initial event has two Democrats and two Republicans. We are a country with two political parties, and politics is conducted through two political parties. You can’t really have a good lens unless you include both.

We’re so polarized as a nation. Do you find that Republicans and Democrats have the same sense of urgency in working together on these security issues?

Among some, not all.

The Republicans who I’ve been working with I would characterize as being more moderate and oriented to problem-solving, as opposed to being ideological actors.

Thinking of the next five years, what impact do you hope the center can have on the U.S. political dialogue around these security issues?

The challenge, as you can appreciate, is getting the center up and running.

Berkeley has enormous expertise among its faculty, but one of the functions of the center is to create a kind of a security studies umbrella for Berkeley, which it previously has not had.

Also, we really want to strive to educate a diverse generation of security professionals.

My anticipation is that those who work with the center will have a larger public profile, as a result, and that the work of the center will be used in Washington, both by people on the policy side and on the political side, by the executive branch and the legislative branch, and that we’ll see the products of the center cited and used.