More gentrification, displacement in Bay Area forecast

The San Francisco Bay Area’s transformation into a sprawling, exclusive and high-income community with less and less room for its low-income residents is just beginning, according to UC Berkeley researchers who literally have it all mapped out.

The interactive Urban Displacement Project map, released today by a Berkeley team, indicates the displacement crisis is not yet half over, as rising housing prices and pressure on low-income residents to relocate to the outer suburbs accelerate.

The project, headed by UC Berkeley researcher Miriam Zuk and city and regional planning professor Karen Chapple, is the product of nearly two years of community-engaged research looking at gentrification and displacement, and involving dozens of local nonprofit organizations and regional agencies. The project is funded by the Bay Area’s Metropolitan Transportation Commission and California’s Air Resources Board to determine the effect of transit and other public investment on displacement, and to search for ways to ensure future housing affordability.

Key research findings, which Zuk and Chapple say offers lessons for other regions across the country where housing prices are skyrocketing, include:

- In 2013, more than 53 percent of low-income households lived in neighborhoods at risk of or already experiencing displacement and gentrification pressures, comprising 48 percent of the Bay Area’s census tracts.

- Neighborhoods with rail stations, historic housing stock, an abundance of market-rate developments and rising housing prices are especially in danger of losing low-income households.

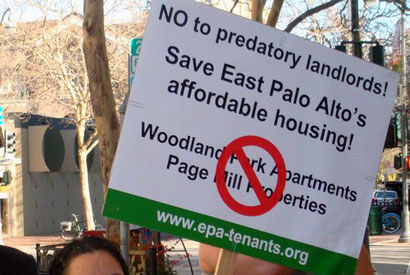

- Despite continued pressures and much anxiety, many neighborhoods that expected to be at risk of displacement — such as East Palo Alto, Marin City and San Francisco’s Chinatown — have been surprisingly stable, at least until 2013, the most recent year with available data. This is likely due to a combination of subsidized housing production, tenant protections, rent control and strong community organizing.

What about my neighborhood?

“Using our online map allows residents, neighborhood groups and governments to assess where their neighborhoods — or those next door — are in terms of the risk and actual occurrence of gentrification and displacement,” says Zuk.

The Urban Displacement Project zeroes in nine neighborhoods in six Bay Area counties that were selected to represent the region’s diverse geographies and neighborhoods in different stages of displacement and gentrification:

- San Francisco’s Chinatown, which has survived decades of housing pressures, managing to preserve affordable housing through strong community organizing and planning

- The Mission District (San Francisco), known locally as the epicenter of gentrification and displacement because much of its industrial land is turning high-end residential

- San Jose’s Diridon transit hub (Santa Clara County), with its stops for Caltrain, Amtrak, VTA light rail and bus lines, as well as a planned stop for a BART extension and high-speed rail is a hotbed for pricey development

- Oakland’s MacArthur BART (Alameda County), a scene of rapid demographic and physical change linked to a revitalized Temescal commercial district, proximity to affluent neighborhoods and transit access

- Redwood City (San Mateo County), where active redevelopment is paying little attention to affordable housing for its low-income workforce

- San Rafael’s Canal neighborhood (Marin), an “immigrant gateway” for families first from Vietnam and now from Latin America

- Marin City (Marin), protected by a large public and subsidized housing stock but the focus of fear of gentrification due to proximity to high-income neighborhoods and limited land that can be developed

- East Palo Alto (San Mateo) risks losing its reputation as “an island of affordability in a sea of wealth”

- Monument Corridor (Contra Costa), an immigrant gateway in Concord, was hit hard by the recession and is primed for higher-income residents

Early-warning tool

The Urban Displacement Project map also serves as a regional early-warning system at the census tract level, with classifications ranging from not losing low-income housing to advanced gentrification and advanced exclusion of low-income housing.

With the click of a mouse, map visitors can zoom in for micro and macro views of communities to learn the percentage of renters in an area, how many households are low-income, the median household income and its changes in recent years, the housing stock age and other data.

While neighborhoods such as San Francisco’s Mission District are often targets of public outcry about gentrification and the negative influences of the tech industry, Zuk and Chapple find even affluent communities that have pockets of low-income housing are in jeopardy.

For example, some neighborhoods in the Peninsula and South Bay communities of San Mateo and Mountain View have lost nearly a quarter of their already small low-income communities over the last decade.

And east of the Oakland hills, the researchers say, Concord’s Monument corridor is being primed for gentrification, putting an estimated 37,000 mostly low-income residents, who are often undocumented and uncounted in official tallies, in jeopardy. The area’s vacancy rate jumped from 3 to 9 percent between 2000 and 2013, and the researchers say landlords may prefer to leave units empty instead of paying maintenance costs or waiting for the market to rebound. Meanwhile, developers can buy in the area cheaply, rehabilitate units and still turn a profit.

Regional can trump local

Subsidized housing and tenant protections such as rent control and just-cause eviction ordinances are the most effective tools for stabilizing communities, say Zuk and Chapple, yet the regional nature of the housing and jobs markets has managed to render some local solutions ineffective.

“Even if San Francisco, Berkeley and East Palo Alto protect their renters, that won’t ease displacement pressures on the communities next door, which are experiencing the same housing market dynamics,” says Chapple.

Oakland’s MacArthur neighborhood has seen dramatic shifts in its composition over the last 30 years. In 1980, 14 percent of residents had a college degree, and in 2013 the number reached 38 percent, a trend the researchers say is due largely to newcomers moving in, drawn by lower rents and more public transportation options than elsewhere in the region.

New strategies

Given the extensive need for affordable housing, the researchers caution the public and decision-makers against thinking that the region can build its way out of the problem by only producing market rate units, recommending the development of new policies to preserve housing affordability and increase the number of affordable units.

In East Palo Alto, a community known for its activism, city officials in 2014 eased restrictions on secondary dwelling units to try to address housing pressures. And all 21 jurisdictions within San Mateo County joined forces for a countywide housing plan update along with impact fees for new commercial and residential development to support affordable housing.

“Our research shows some new strategies that can help stabilize communities and keep them affordable,” Zuk says, noting that the tools involve ways to produce and preserve subsidized units, and to promote community organizing.

In addition to working with a range of community organizations, the researchers also based their findings on data from the U.S. Census, county tax assessors and real-estate transactions, as well as interviews and field observations.

The researchers conducted their neighborhood case studies in collaboration with seven community-based organizations to ground the technical analysis in real-life experiences. Two technical advisory committees comprised of local and statewide stakeholders provided oversight.

See maps and reports on the Urban Displacement website.

Related information:

The future of displacement (Berkeley Blog post by Karen Chapple, Aug. 25, 2015)

Research profile for Karen Chapple