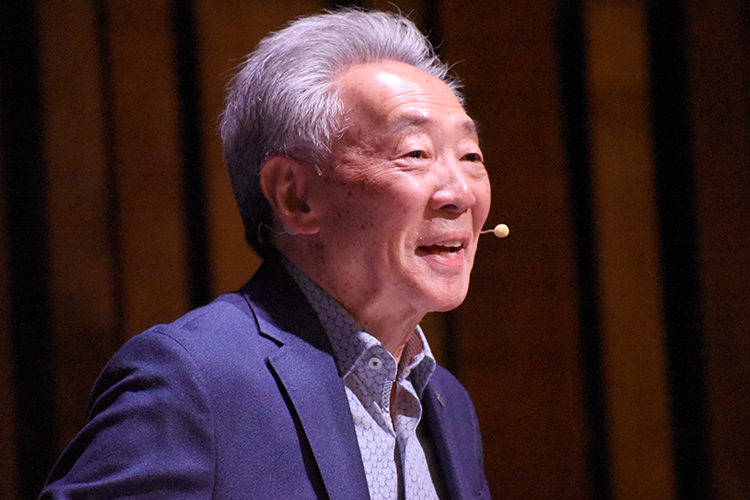

Michael Omi: How asking questions can lead to empowering others

As a child growing up in San Francisco’s Fillmore District, Michael Omi had a knack for chemistry. The way molecular structures are used to design new medicines fascinated him so much he wanted to be a pharmacist.

But coming to UC Berkeley as an undergraduate student in 1969, Omi was thrust into a tumultuous time in American history, where street conflicts between student organizers and police were a daily occurrence, and blockades of National Guardsmen were commonplace on a campus rife with protests against the Vietnam War.

“I remember a helicopter that descended around campus spewing tear gas to disperse crowds,” said Omi. “As a student I’m thinking, ‘What is this? Why is this happening?'”

Omi found the answers to his questions in the first ethnic studies classes taught at Berkeley, courses that the Third World Liberation Front — a coalition of ethnic student groups — fought to implement on college campuses across California.

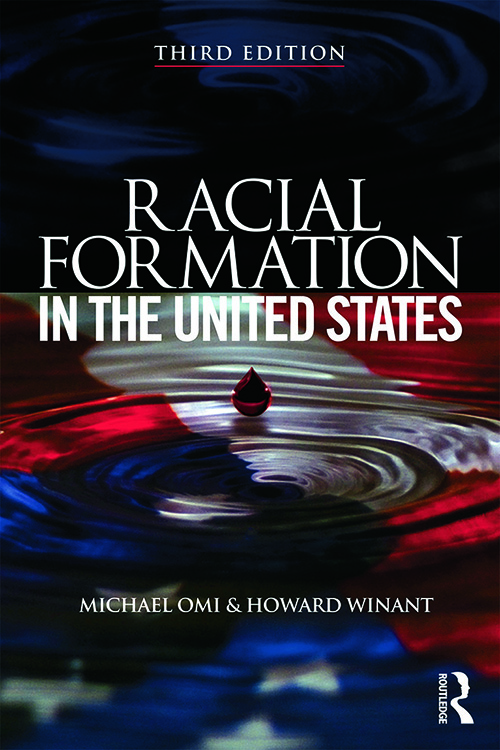

That knowledge, Omi said, was “incredibly empowering” and would eventually lead to a distinguished 35-year career as a Berkeley educator, activist and pioneering researcher. In 1986, with UC Santa Barbara professor Howard Winant, Omi co-authored the book Racial Formation in the United States. The text has become a seminal work in the study of race in America, and is still taught in universities across the country.

Omi recently retired from Berkeley’s ethnic studies department and will be honored by faculty, friends and students in a daylong commemoration held at the Berkeley Faculty Club on Friday, Oct. 1. A portion of the festivities will also be held virtually.

“I’ve had the opportunity and enormous satisfaction of working with students,” said Omi, who still plans to stay connected to Berkeley’s campus community. “As an educator, watching them rethink what their place is in the world, and ask important questions that help them see society through a different lens, has truly been a pleasure.”

Berkeley News recently spoke to Omi about how his theory of racial formations have stood the test of time, what ethnic studies scholars need to focus on moving forward and why public discourse about the impact of race on American society is still important.

Berkeley News: Your theories on racial formation in America were considered by many as revolutionary at the time. From the introduction of the very real racial hierarchies that exist, to seeing the concept of race solely as a social construct. Is it sad to see some of the same racial issues you identified more than 35 years ago still present in American society today?

Michael Omi: Yes, it is. Howard Winant and I really wanted to suggest how the concept of race takes root and unfolds across time and place.

But saying that race is a social concept is also kind of insufficient. You have to say how it has been given meaning: What are the ideologies that attach themselves to it? How is race used as a principle of stratification to determine people’s access to jobs, housing healthcare and et cetera?

We have since learned a lot from scholars who have used some of the basic concepts of racial formation theory and really applied and extended them in ways we didn’t even imagine. And in some instances, revealed its limits.

There’s a tremendous amount of continuity between then and now. And it really reaffirms the centrality of race in U.S. politics and culture. If you think about everything that’s going on — the pandemic has certainly underscored the structure of racial disparity with respect to who our front-line workers are and who are able to get vaccinated.

The killing of George Floyd, among other Black men and women, continues to raise issues around policing and mass incarceration in the United States. We now have voter suppression laws going on in many states diluting the voting power of groups of color. And you have Asian Americans going from being seen as a “model minority” to a racial threat.

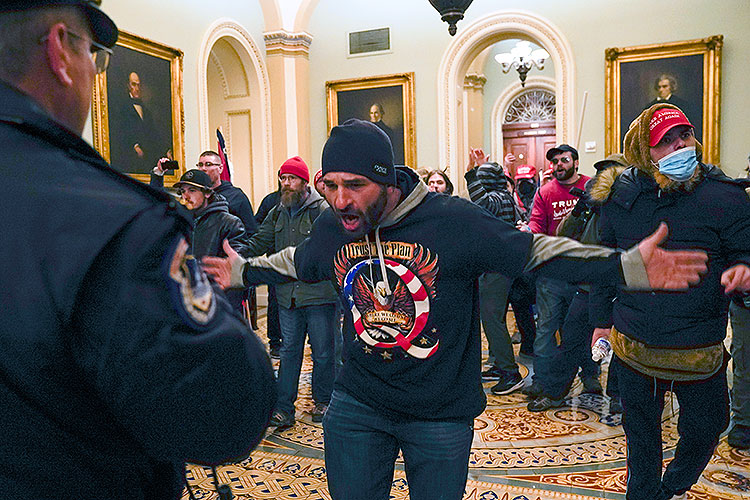

All of these things — including the Capitol insurrection — reaffirm the centrality of race in contemporary politics.

How does the Capitol insurrection relate to race in America?

I think this really was a response to the unprecedented scale of contemporary human migration, and the national and global impact of neoliberalism on economic policies.

And it’s being driven by fears of cultural disintegration and the supposed “loss of national identity and solidarity.” There’s a lot of talk about the fear of “white replacement,” and I think it’s really important for us to pay attention to this given the increasingly diverse racial demographic trends.

What will that look like for white people? Throughout U.S. history, fears of white replacement have generated major political movements like the Know-Nothing Party and different incarnations of the Ku Klux Klan. Current groups such as the Proud Boys, the Oath Keepers and the Boogaloo Boys are merely the most recent expression of this political reaction, animated by the fear of white men falling in status and grace.

Seems like history repeating itself. Do you think anything has changed this time around?

Yes, I do. There’s been a much wider acceptance of the notion of systemic racism than there was before, and we actually have major corporations talking about this. That is an important discursive shift in some ways, though I doubt that “big business” really knows what systemic racism is.

We’ve also gone from seeing racism as being just individual expressions of hostility, violence or bias, to understanding the institutionalized and structural ways in which race and racism manifest themselves.

You’ve taught so many classes over the years. What research or curriculum do you hope ethnic studies academics continue to focus on?

I think oftentimes, we look at different groups in isolation from one another. So, it’s really important for scholars of race to take a more relational approach to understanding how groups are differentially racialized, and how these groups are continually shaping the conditions for each other’s existence.

This is important discourse we need to engage in with our students.

For the past few years I have taught an undergraduate seminar that focused on the racialization of both the Black and Asian American communities, and how they can be complicit in oppressing each other.

In a racial hierarchy, we are all positioned differently and possess different amounts of power in society, so it is sometimes hard to relate to one another, much less forge coalitions with other groups. In the course I offered, I’ve been able to witness students from all backgrounds think more deeply about how to create solidarity between and among different communities of color.

How can scholars progress the study and discourse around acts of racial violence against these communities of color?

I think it is really important for scholars to delve more into is how racial dynamics on the macro level impact the micro. And by that, I mean the relationship between institutions and structures to individual interactions.

How can we explain, for example, what motivates someone to violently attack an elderly Asian American person in the street? What’s the connection between larger ideological beliefs, structural context and individual motives?

Something I would hope also gets more attention is this notion of what anti-racism is. We might need to define this concept for folks as I think it’s a bit underdeveloped as to what we mean by an anti-racist practice or policy. What would an anti-racist movement focus on and define? I think we need much more specificity.

What should that specificity be?

At this point, we may be at the point of realizing the limits of the civil rights paradigm. The continued pervasiveness of racism in the U.S. suggests that civil rights reforms may be insufficient in challenging entrenched patterns of racial inequality.

It’s not enough.

So, we need to collectively ask ourselves: What would a movement that seriously considers structural racism do? And what are the kinds of institutions that need to be transformed to accomplish that? How could addressing these questions impact our economy? Our policy? Our healthcare system? And so forth.

All of that needs to be thought through in order to effectively challenge systemic and structural forms of racism.

As you say farewell to Berkeley, how do you think the campus has helped you grow throughout the years?

Berkeley is an amazing place and it has helped me grow and mature as a teacher and as a person.

I’ve had the opportunity and enormous satisfaction of working with students. As an educator, watching them rethink what their place is in the world, and ask important questions that help them see society through a different lens, has truly been a pleasure.

I’ve also learned so much from the work of scholars in different departments, schools and institutes across this campus. To come in contact and be engaged in conversations with them throughout the years: That’s been a real joy and a continual learning experience.

Oftentimes I’ve learned a lot from people I disagree with. And it’s allowed me to appreciate opinions that differ from mine. It’s important to be able to reach across the divide and think deeply about the positions of others.

And whether you agree or not, those conversations, and asking those questions, will help you to grow in more ways than one.