It Don’t Mean a Thing if the Brain Ain’t Got That Swing

Like Duke Ellington’s 1931 jazz standard, the human brain improvises while its rhythm section keeps up a steady beat. But when it comes to taking on intellectually challenging tasks, groups of neurons tune in to one another for a fraction of a second and harmonize, then go back to improvising, according to new research led by UC Berkeley.

These findings, reported today in the journal Nature Neuroscience, could pave the way for more targeted treatments for people with brain disorders marked by fast, slow or chaotic brain waves, also known as neural oscillations.

Tracking the changing rhythms of the healthy human brain at work advances our understanding of such disorders as Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia and even autism, which are characterized in part by offbeat brain rhythms. In jazz lingo, for example, bands of neurons in certain mental illnesses may be malfunctioning because they’re tuning in to blue notes, or playing double time or half time.

“The human brain has 86 billion or so neurons all trying to talk to each other in this incredibly messy, noisy and electrochemical soup,” said study lead author Bradley Voytek. “Our results help explain the mechanism for how brain networks quickly come together and break apart as needed.”

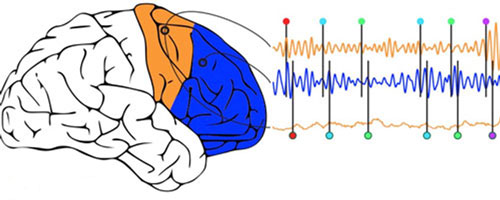

Voytek and fellow researchers at UC Berkeley’s Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute measured electrical activity in the brains of cognitively healthy epilepsy patients. They found that, as the mental exercises became more demanding, theta waves at 4-8 Hertz or cycles per second synchronized within the brain’s frontal lobe, enabling it to connect with other brain regions, such as the motor cortex.

“In these brief moments of synchronization, quick communication occurs as the neurons between brain regions lock into these frequencies, and this measure is critical in a variety of disorders,” said Voytek, an assistant professor of cognitive science at UC San Diego who conducted the study as a postdoctoral fellow in neuroscience at UC Berkeley.

Previous experiments on animals have shown how brain waves control brain activity. This latest study is among the first to use electrocorticography – which places electrodes directly on the exposed surface of the brain – to measure neural oscillations as people perform cognitively challenging tasks and show how these rhythms control communication between brain regions.

There are five types of brain wave frequencies – Gamma, Beta, Alpha, Theta and Delta – and each are thought to play a different role. For example, Theta waves help coordinate neurons as we move around our environment, and thus are key to processing spatial information.

In people with autism, the connection between Alpha waves and neural activity has been found to weaken when they process emotional images. Meanwhile, people with Parkinson’s disease show abnormally strong Beta waves in the motor cortex. This locks neurons into the wrong groove and inhibits movement. Fortunately, electrical deep brain stimulation can disrupt abnormally strong Beta waves in Parkinson’s and alleviate symptoms, Voytek said.

For the study, epilepsy patients viewed shapes of increasing complexity on a computer screen and were tasked with using different fingers (index or middle) to push a button depending on the shape, color or texture of the shape. The exercise started out simply with participants hitting the button with, say, an index finger each time a square flashed on the screen. But it grew progressively more difficult as the shapes became more layered with colors and textures, and their fingers had to keep up.

As the tasks became more demanding, the oscillations kept up, coordinating more parts of the frontal lobe and synchronizing the information passing between those brain regions.

“The results revealed a delicate coordination in the brain’s code,” Voytek said. “Our neural orchestra may need no conductor, just brain waves sweeping through to briefly excite neurons, like millions of fans in a stadium doing ‘The Wave.’”

Other co-authors and researchers on the study are Mark, Robert Knight and David Fegen at UC Berkeley, David Badre at Brown University, Andrew Kayser at the Department of Veterans Affairs in Martinez, Calif., Edward Chang at UCSF, Nathan Crone at Johns Hopkins University and Joseph Parvizi at Stanford University.