How Preserving a Country’s Languages Can Lead to Decolonization

As a child in the Philippines during the 1970s, Joi Barrios-Leblanc remembers singing songs that glorified the country’s president Ferdinand Marcos, and his U.S-backed regime of martial law that turned the government into a one-man dictatorship that killed, tortured and incarcerated thousands of its citizens.

The songs sung in Tagalog — the Philippine national language — were slogans of propaganda that stressed the need for the populace to be submissive, disciplined and loyal for the country to prosper, said Barrios-LeBlanc, a UC Berkeley senior lecturer in South and Southeast Asian Studies.

Barrios-Leblanc grew up to become an activist, writer and academic who opposed Marcos’s rule. A few weeks ago, she witnessed Philippine voters, once again, sing similar songs for Marcos’s son, Bongbong Marcos, who won the 2022 presidential election in a landslide nearly 60 years after his father first assumed office.

“Same tune, same name,” she said.

Looking back, Barrios-Leblanc said, those songs are powerful representations of how the use of language can sustain colonial thought processes and suppress the truth. But the power of language can also be used to decolonize our histories — by placing the experiences of the colonized at the center of those narratives — and as “part of a larger movement towards political change,” she said.

“We need to look at the languages we use as being part of the whole conversation around the efforts of decolonization,” said Barrios-Leblanc, who has taught courses at Berkeley that delve into Indigenous beliefs in Philippine literature and art, cultural politics and examining film through a decolonized lens. “Language is the doorway to understanding culture and heritage.”

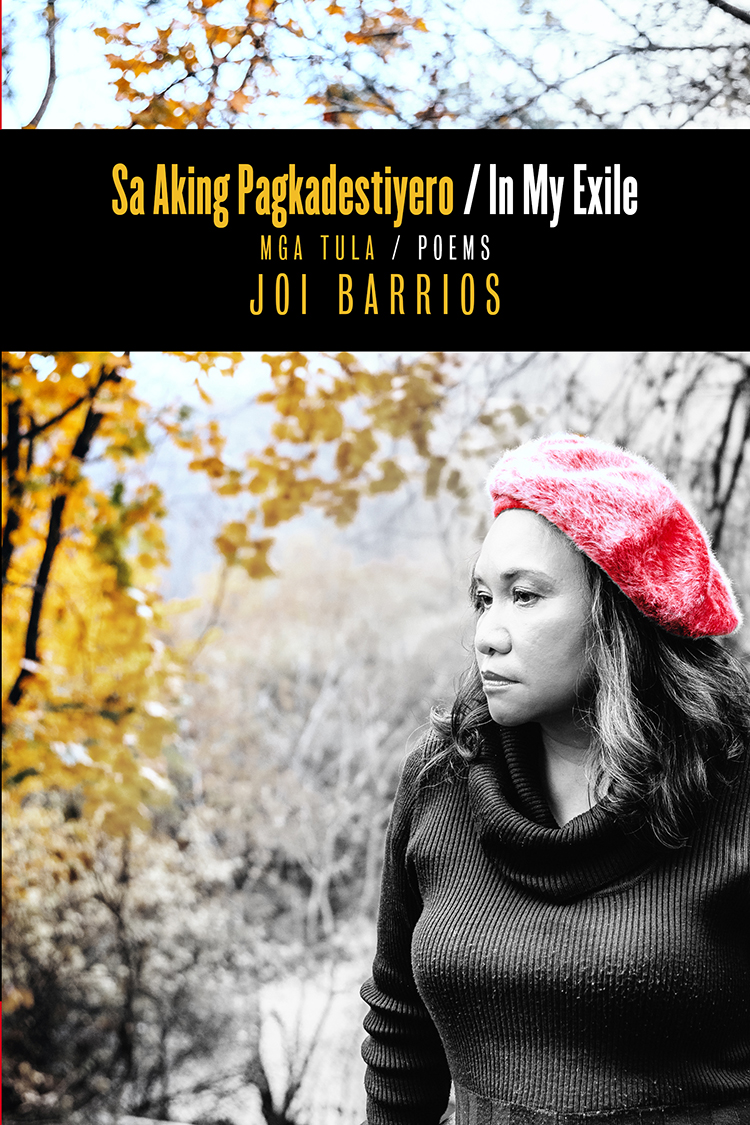

For more than 15 years Barrios-Leblanc’s research has focused on promoting Philippine language and literature. She has published several Philippine language textbooks and award-winning collections of poetry. Her new book Sa Aking Pagkadestiyero, or In My Exile, will be released this July and reflects on Barrios-Leblanc’s life through poetry.

Most recently, she received a lifetime achievement award in literature from the National Language Commission of the Philippines (Komisyon ng Wika).

Berkeley News spoke with her about the role that literature can play in impacting political movements, and why preserving Philippine languages is important work in the efforts toward decolonization.

Berkeley News: How does a country’s literature impact its politics?

Barrios: It actually goes both ways.

On one hand, the literature that we write does not exist in a vacuum, meaning writers are constantly influenced by the socioeconomic and political factors in society: What is going on in the streets of the Philippines? Poverty? Protest? What type of government is causing all of this to happen?

Asking and answering those types of questions is what writers do with their literature, in their own unique ways. And even the politics around the production of literature, and who owns the printing presses, also impact censorship. But at the same time, I’d like to believe that literature has always been part of a larger movement toward political change.

For example, if you look at 19th century Philippine literature you’ll find in the Kalayaan (Freedom) newspaper archives of poetry written in Tagalog (the language Filipino is primarily based on), by Andres Bonifacio, a Filipino revolutionary leader who fought against Spain, using these poems to translate his ideas and thoughts about the resistance to Spanish rule.

So, the literature was a part of their work as revolutionaries. You have resistance literature because there are resistance movements.

Speaking and writing in English is very commonplace in the Philippines. Why do we need literature that is written in Philippine languages?

We need to look at language as being part of the whole conversation around the efforts of decolonization because language is the doorway to understanding culture and heritage. We also have to think critically about the reasons a language is, or isn’t, being used.

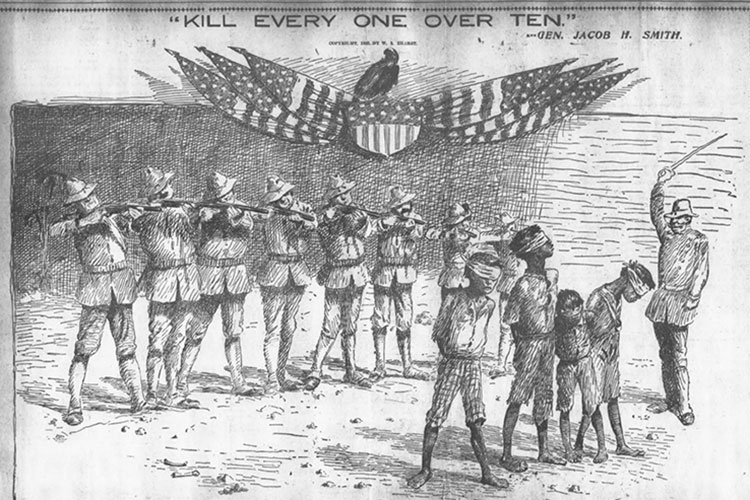

For example, during the American occupation in the Philippines, English was imposed on the country by people like (former UC president) David Barrows, and it created a situation where English automatically became the language of the privileged. And so, people tended to look down on others who spoke Tagalog or any of the other 120 or so Philippine languages. English writers also looked down on writers who wrote in their native Filipino languages.

Language impacts literature and how it is perceived.

We still see that impact now with first-generation Filipinx Americans, whom many are not being taught Philippine languages because their parents wanted to shield them from having an accent or being discriminated against in America, from being seen as less American.

But do you need to understand a country’s native languages to know its history?

Yes, I think you do, because there are colonial narratives that hide a lot of history. And the language is the history. If we don’t preserve it, we lose our history.

When it comes to the Philippines, a lot of people are not aware that in precolonial times, before the Spanish and Americans came, people were not illiterate. They had their own writing script, the baybayin. But colonizers cut off the opportunities for Filipinos to read that text and the first archives of Philippine history and culture.

If you look at the history of Philippine literature, most of the important texts were written in Tagalog, our country’s national language. So, if you want to know more about the history of World War II in the Philippines, you’re going to want to read the literature of the Hukbalahap guerillas that fought against the Japanese.

The texts about the songs they sang in Tagalog are a trove of information because a lot of the guerillas couldn’t read or write. But they sang songs during warfare that described what they were experiencing and what they did to push the Japanese out of the country.

Examining those songs help us to reexamine the false historical narrative that America singlehandedly saved the Philippines from the Japanese. And there are so many more.

In this context around decolonizing our history, when it comes to historical literature and music, should their significance be considered one and the same?

I don’t think we should separate the impact they have individually, but rather examine them as a whole and how they reveal suppressed histories and languages through their translations.

During the Spanish occupation, Filipinos had songs written in Tagalog they called the kundiman de revolucion, meaning a love song to the revolution. And that music would represent the resistance, but the lyrics described a love that’s unfulfilled — an expression for this freedom they hadn’t obtained from colonizing countries.

But while songs and literature can reveal our political histories, and vice versa, those words, and the way they are used, also can change depending on the politics of the time.

Interestingly, a song like “Bayan Ko” (“For My Country”), was first written and sung as an anthem against American occupation, but throughout the years has become an unofficial national song to express patriotism in the Philippines. The song was also used during martial law by opponents of Ferdinand Marcos at rallies.

A lot of people did not realize that because they did not have access to the language that describes that history of resistance in the Philippines. So, preserving a country’s languages, I think, is extremely important if we want to decolonize our history, research and so forth.

Should this effort to preserve languages be something that other countries, with similar colonial histories as the Philippines, consider when continuing the work of decolonization?

I think that all countries who have gone through colonization, to truly appreciate the need to constantly fight for sovereignty is first to understand what the colonization is, and what it entails.

Understanding all languages are important in this process, because with language comes access to culture and access to the works written in that language. So, you can get a deeper understanding of your roots, of your people and your colonial histories.

Using our language to move toward decolonization will always lead us to the whole discourse on empire and how that still impacts us today.

Right now, Indigenous people in the Philippines are still experiencing militarization from western mining companies that have shut down their schools and trampled all over their rights. And when you think about the case of Jennifer Laude, a transgender woman who was killed by a U.S. Marine in 2014, all of this is just another reminder of the violent history of American capitalism and militarism in the Philippines.

It is all interconnected.

And while we can’t be decolonized overnight, we can take steps. Whether it is unnaming Barrows Hall on campus or creating a center for Philippine languages — which is the vision I share with Filipino language instructors and staff at Berkeley, other UC campuses and universities — we need to continue to move in that direction.

We need to come together as a community to fight for what our community needs. We’re teaching our students to have courage and we’re teaching them to fight for what is right. As Filipinos, we’ve always had a history of struggle. A struggle against colonizers, a struggle against dictatorships — it’s a struggle against tyranny.

So, all I can say is we know how to struggle, and we have always fought against our oppressors. Why should we stop now?