Focusing on a key event in life of a chromosome

Unless you are in a field of study related to cell biology, you most likely have never heard of Ndc80. Yet this protein complex is essential to mitosis, the process by which a living cell separates its chromosomes and distributes them equally between its two daughter cells. Now, through a combination of cryo-electron microscopy and three-dimensional image reconstruction, a team of researchers with the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California (UC) Berkeley have produced a subnanometer resolution model of human Ndc80 that reveals how this unsung hero carries out its essential tasks.

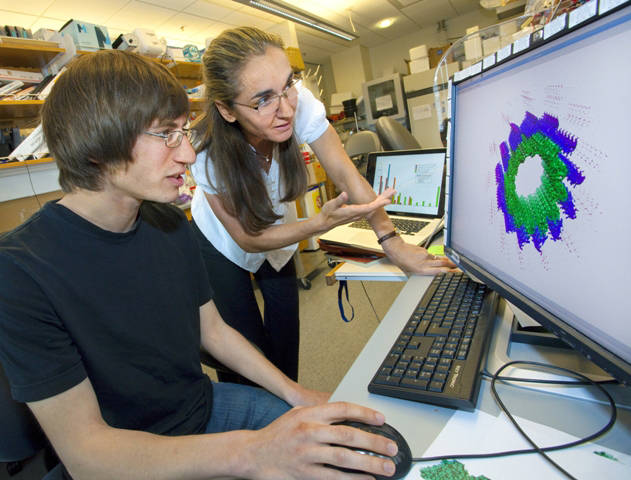

“Our model suggests that Ndc80 oligomerizes on the surface of the microtubule via a segment of the protein that is regulated so that correct attachments are maintained and incorrect attachments are discarded,” says biophysicist Eva Nogales who led this study.

“What we propose is that this oligomerization is an important part of the mechanism by which Ndc80 is able to utilize the energy of microtubule disassembly to move chromosomes towards the spindle poles during mitosis. This oligomerization will only happen for correctly attached microtubules”

Nogales holds joint appointments with Berkeley Lab’s Life Sciences Divisions, UC Berkeley’s Molecular and Cell Biology Department, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. An expert on electron microscopy and image analysis and an authority on the structure and dynamics of microtubules, she is the corresponding author of a paper published in the journal Nature titled, “The Ndc80 kinetochore complex forms oligomeric arrays along microtubules.”

Co-authoring the paper with Nogales were Gregory Alushin, Vincent Ramey, Sebastiano Pasqualato, David Ball, Nikolaus Grigorieff and Andrea Musacchio.

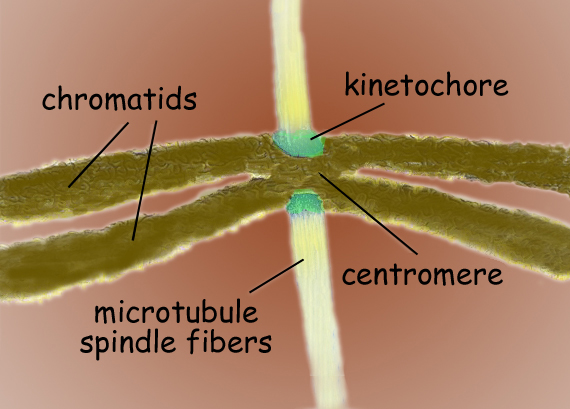

Biological cells have a cytoskeleton that gives shape to membrane walls and other cellular structures and also controls the transportation of substances in and out of the cell. This cytoskeleton is spun from tiny fibers of tubulin protein called microtubles. During mitosis, microtubules disassemble and reform into spindles across which duplicate sets of chromosomes line up and migrate to opposite poles. After chromosome migration is complete, the microtubules disassemble and reform back into skeletal systems for the two new daughter cells.

Mistakes in the distribution of chromosomes from a parent cell to its daughter cells can lead to birth defects, cancer and other disorders. To ensure that each daughter cell receives a single copy of each chromosome, microtubule spindles dock with each chromosome’s centromere – the central region where its two chromatids connect. The microtubule spindles connect with the centromere through a network of proteins called the kinetochore. Ndc80 is a key member of the kinetochore network and serves as a sort of “landing pad” for the microtubule-centromere connection. Although Ndc80’s genetics and biochemistry have been extensively characterized, the mechanisms behind its activities have until now remained a mystery.

“Our first ever subnanometer model of Ndc80 shows that the protein complex binds the microtubule with a tubulin monomer repeat that is sensitive to tubulin conformation,” Nogales says. “Furthermore, Ndc80 complexes self-associate along microtubule protofilaments via interactions that are mediated by the amino-terminal tail of the Ndc80 protein, which is the site of phospho-regulation by the Aurora B kinase.”

The Aurora B kinase is an enzyme that ensures the correction of any improper microtubule-kinetochore attachments – faulty attachments will result in unequal segregation of the genetic material, such as both chromatides going to the same daughter cell. In their paper, Nogales and her co-authors contend that Ndc80’s mode of interaction with the microtubule and its oligomerization provide a means by which the Aurora B kinase can regulate the stability of the load-bearing Ndc80-microtubule attachments.

“The Aurora B kinase corrects wrong microtubule-kinetochore attachments by phosphorylating proteins in the kinetochore,” Nogales says. “Ndc80 is a major substrate of this regulation. Our work shows that if phosphorylated by Aurora B, attachments are not robust because there is no oligomerization of Ndc80s.”

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Berkeley Lab is a U.S. Department of Energy national laboratory located in Berkeley, California. It conducts unclassified scientific research for DOE’s Office of Science and is managed by the University of California. Visit our Website at www.lbl.gov/

Additional Information

For more information about Eva Nogales and her research group see http://cryoem.berkeley.edu/