‘Eye in the sky’ sensors reduce stress of in-home dementia care

People caring around the clock for a parent, spouse or other loved one with dementia are at a high risk for clinical anxiety, depression, social isolation and even suicidal ideation, according to longitudinal research from UC Berkeley.

But thanks to a blend of artificial intelligence (AI) and behavioral science, relief may be on the horizon.

UC Berkeley psychologists have joined forces with People Power, a home healthcare tech company, to install networks of sensors that hook up to AI and smartphone technology in the homes of some 350 dementia patients nationwide.

“The sensors are designed to provide a sort of ‘eye in the sky’ that doesn’t get tired and gives caregivers a break,” said study principal investigator Robert Levenson, a UC Berkeley psychology professor whose research team presented the findings this week at the virtual annual convention of the Association for Psychological Science.

In two randomized controlled trials, Levenson’s research team and People Power sought to find out if having in-home sensors track people’s activity, including their use of doors, stoves, water faucets and medicine cabinets — and activate alerts if something seems amiss — could improve the mental health of familial caregivers.

So far, not bad.

“We are trying to take the pressure off what we think is leading to anxiety and depression for familial caregivers who are on duty 24/7,” Levenson said. “Though we don’t have a cure for declines in caregiver health, we have evidence that this approach is a step in the right direction.”

Peace of mind

Indeed, preliminary results indicate that caregivers who got the maximum package of sensors — and received and responded to more text alerts — experienced a significant drop in anxiety after the first three months of the experiment.

“I was a brand new, sleep-deprived caregiver … running up and down stairs every time my father made a noise,” wrote one study participant in a testimonial. “People Power gave me back my peace of mind. I could glance at the app, check his whereabouts, and close my eyes again reassured that he was safe.”

Funded with a $4.5 million grant from the National Institute on Aging, the public-private collaboration is particularly salient in the face of a rising tide of aging baby boomers, many of whom are entering a period of cognitive decline.

By 2030, more than 8 million Americans are anticipated to be living with some form of dementia, and many will depend on round-the-clock in-home care.

An earlier study led by Levenson’s Psychophysiology Lab found that dementia patients who were tended by caregivers with depression and anxiety typically died sooner than those being looked after by caregivers in good mental health.

A serendipitous marriage

The idea for an in-home monitoring system to ease the burden of dementia caregivers came up in 2015 when Levenson was at a wedding and met Gene Wang, CEO of People Power, and David Moss, the company’s chief technology officer.

They discussed People Power’s work on in-home monitoring technology and senior care, and Levenson’s work on protecting the health of dementia caregivers, and marveled at how their areas of expertise overlapped. Thus began their collaboration.

When Wang and Levenson applied for a small business innovation grant from the National Institute on Aging, they were surprised to find that their submission was fast-tracked and qualified for a much larger grant than anticipated because applied research of this nature is deemed a priority in the face of the pressing needs of an aging population.

How they conducted the study

The first experiment was launched in fall 2019 and covered 63 homes of dementia patients in the San Francisco Bay Area, half of which received the maximum level of sensor monitoring and alerts while the other half, the control group, received the bare minimum.

Caregivers were randomly assigned to either the maximum or minimum monitoring conditions, with neither the researchers nor those installing the systems knowing what level of service each caregiver in the study had been given.

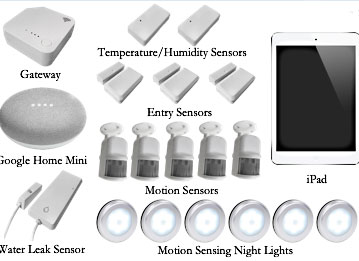

The minimal control system monitored only for water leaks and temperature deviations. The maximum system, when fully activated, detected if doors or refrigerators or medicine cabinets opened or closed. It could also tell if a faucet had been left running or a stove left on, or if a person with dementia was wandering aimlessly or had fallen.

Once the AI system tracked typical patterns of activity for a while in each home, it could detect conditions and activity outside the norm and send out alerts.

“If it’s a false alarm, the software learns and readjusts the threshold,” Levenson said. “If it turns out that something bad has happened, the alert can be directed to a friend or family member to come over and help, or escalated to call an emergency service, if needed.”

“The point is, this goes on all the time, even when the caregiver is asleep or watching TV or out at the store or at work,” he added. “It’s not perfect, but it offers an important backstop, some much-needed extra support for caregivers.”

Meanwhile, a second larger and more ambitious study of nearly 300 homes of people with dementia in the U.S. is being conducted by Levenson’s team and People Power, and is expected to wrap up in September.

In addition to Levenson, the study’s researchers are Yuxuan Chen, Darius Levan, Clarissa Munoz, Kuan-Hua Chen, Claire Yee and Casey Brown at UC Berkeley, and Gene Wang and David Moss at People Power.