Do Vowels Have Colors? According to Some With Synesthesia, Yes.

In her new book, On the Colors of Vowels: Thinking Through Synesthesia, UC Berkeley Professor Liesl Yamaguchi discusses the history of the rare neurological condition and the unique ability of scholars in the humanities to investigate the phenomenon.

It’s hard to pinpoint when synesthesia, the rare neurological condition where a stimulus that affects one sense prompts a response in a different sense, was first documented. Scientific literature marks its beginning in 1812, when it appeared as an aside in a Bavarian medical student’s dissertation. Toward the end, there’s a small section where he detailed how he associated musical tones and letters with colors.

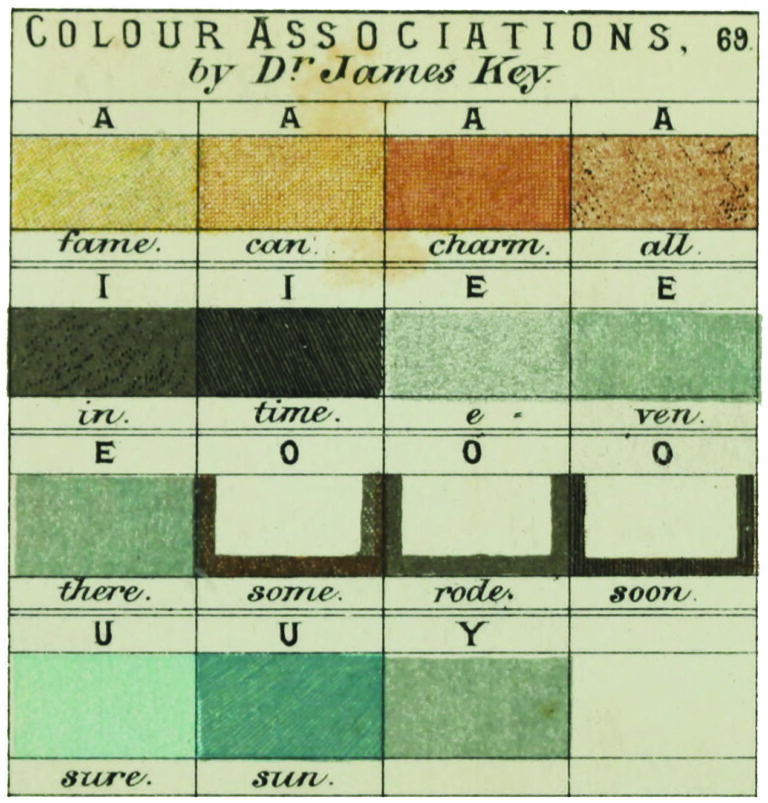

“He enumerates the colors he sees in connection with the letters of the alphabet. A and E: vermilion, I: white, O: orange and so forth,” says UC Berkeley French Professor Liesl Yamaguchi, author of the new book, On the Colors of Vowels: Thinking Through Synesthesia.

Yamaguchi’s book, which she’ll be discussing in a Berkeley Book Chat event on April 9, investigates how the concept of synesthesia emerged in the 19th century, despite the fact that everything we know about this way of sensing suggests that it’s likely “an age-old phenomenon.”

In fact, the word “synesthesia” was used in ancient Greece, but to describe a simultaneous feeling felt by two different people at once. The modern use of the term dates only to the late 19th century, and inquiry into its relation to ordinary sensing has only begun to be investigated in the last decade or so.

In this UC Berkeley News Q&A, Yamaguchi discusses the history of synesthesia, and the unique ability of scholars in the humanities to investigate the phenomenon in ways that are methodologically impossible in the hard sciences.

UC Berkeley News: First, can you give a brief overview of the different types of synesthesia? Why did you decide to focus on the colors of vowels in your book?

The most commonly recognized kinds of synesthesia include seeing colors in conjunction with musical sounds (instrumental timbres, keys, tones) or linguistic elements (graphemes, phonemes, words, numbers), though these days many sensory experiences are often considered under the same umbrella term. Experiencing sensations of light or color in response to certain rhythms, for example, might also be studied as a kind of synesthesia, or feeling tactile sensations when seeing others being touched (“mirror-touch synesthesia”). This last type starts to echo with Aristotle’s use of the verb sunaisthanesthai to indicate a “feeling in common,” simultaneously experienced by more than one person.

I decided to delve into the question of vowels because I was curious about poets’ tendency to describe poetic sounds — usually vocalic sounds — in a visual vocabulary (what is the “coloration of a rhyme,” “a brighter timbre,” a “dark vowel”?) I was interested in investigating the relationship between that way of talking about poetic effects and the way that synesthetes talk about seeing colors in conjunction with vowels.

Why does medical student Georg Sachs’ dissertation mark the start date of synesthesia? How far does the phenomenon likely go back?

The Sachs dissertation of 1812 is generally acknowledged as the first document reporting synesthesia in a modern sense. It doesn’t use the word “synesthesia,” but it’s recognized retrospectively as synesthesia because Sachs presents his sensations in a systematic way that’s recognizable to modern science (it is, after all, a medical dissertation explicitly aimed at establishing the author’s authority as a scientist!)

Yet as anyone studying synesthesia will tell you, people have probably been sensing this way for as long as people have existed (or even, paradoxically, before, as there’s little evidence to suggest that this is an exclusively human phenomenon). So the interesting question is why, according to the history of the neurosciences, we have zero documentation of this way of sensing before 1812.

The longer history of synesthesia would go back to the Pythagoreans and harmony of the spheres, but to trace that history requires all sorts of philological skills that aren’t cultivated in the sciences. I don’t go that far back in the book, but I do try to show how more sensitive and agile readings of historical texts can allow us to see glimmers of what we now call “synesthesia.”

One of the big questions that emerges at the center of my book is how we decide to read literally or metaphorically, and if that distinction is always pertinent or discernible. When someone describes a vowel as “bright,” it is often impossible to know if they mean that it has a relationship to luminosity or that it has a certain sound.

In the 19th century, descriptions of vowels’ colors suddenly appeared in discussions across a lot of other fields, from the sciences to the arts. Where do they start showing up, and how was synesthesia perceived by society?

Visual descriptions of vowels turn up in experimental psychology surveys, in physical acoustics, in vocal manuals and discussions of opera, in phonetics, in Indo-European linguistics, and in poetics.

The idea of seeing things that aren’t objectively verifiable is highly stigmatized for most of the 19th century (descriptions are often classified under “mental disturbances,” for example). Subjects generally aren’t willing to give their names for fear of stigmatization, and it’s clearly hard to get people to talk about it. Most of the records that we have are in diaries, letters, asides or anonymous accounts.

There is a shift in how people understand synesthesia in the 20th century. Can you describe what happens and why?

Scientists of the 20th century transform synesthesia into a fundable object of modern science, which requires defining it rigorously (if at times arbitrarily) and limiting its extent to the testable and falsifiable. So over the course of the 20th century, “synesthesia” becomes something that can be tested, that can offer replicable results, that can be discreetly identified as genuine or not.

Over this same period, synesthesia is transformed from a mental disturbance to a sign of genius: It becomes the privileged pathology. Instead of being this embarrassing, strange condition that you should probably not tell people you have, it is associated with exceptional creativity, as this alternative way of seeing the world and organizing information that is particularly generative in the arts.

Do you write about any artists who identified as synesthetes in your book? If so, can you name a few and describe them in a sentence or two?

Well no, I don’t, because no one in the 19th century identified as a synesthetic! The concept hadn’t been codified yet. But several of the thinkers I do write about — for example Stéphane Mallarmé and Ferdinand de Saussure — write things that might well make modern readers suspect that they experienced linguistic sounds in a way that we would call “synesthetic.”

You write that the specter of falsity or fakeness around synesthesia has been there from the beginning. Why has it been so hard for someone to prove they’re a synesthete, and for others to believe it?

Well, the basic premise of synesthesia is that certain subjects experience sensations that aren’t obviously caused by something that others can observe. It wasn’t until the turn of the 21st century that the advent of brain scans showing anomalous activity in sensory cortices furnished any sort of outside validation of what subjects claimed to see. Prior to that, you basically had to just believe the subject’s account. And that’s not great scientific practice, right? No one in the hard sciences is going to be thrilled about that as their method.

The 19th century corpus is rife with the language of “pseudo-” and “false” impressions, but interestingly here the concern isn’t about false reporters, as it is in the 20th century; it’s actually about trying to designate these sensations as not linked to external phenomena that other people can attest to.

One of the casualties of the scientific codification of synesthesia in the 20th century is the variability of the phenomenon. Narrative accounts of synesthetic experience from the 19th century — for example, how vowels are described as changing color depending on which consonants surround them — are full of variation, and become impossible for scientific study when consistency was imposed as the gold standard test for synesthesia in the 20th century.

By the early 21st century, there’s finally some scientific, measurable proof that synesthesia is a real thing that people experience. What advances in technology allowed this to happen, and how did it impact research in the area?

There were CT scans and fMRI in the early days of these technologies that showed aberrant activity in the visual cortex in response to sonorous stimuli. The brain scans provided a kind of verification for the scientific community. That was a very triumphant moment for synesthesia advocates.

The release from this obligation to prove the reality of synesthesia has been helpful in that it has enabled scientists to be more flexible in how they study it, because they’re not constantly having to convince people of its legitimacy. That flexibility has brought the scientific discourse into closer proximity to humanistic studies of the phenomenon, so I think we’re at an exciting moment in which these discourses can begin to interact in more productive ways.

After conducting years of research on synesthesia for your book, how do you define the term now?

It’s more of a cluster concept or a discussion about how humans sense in complex ways, and how the senses interact. I’m interested in the historical ways that we have talked about how we sense things, as I think the language used is often extremely revelatory. Language itself is a sort of archive, if we know how to read it. But knowing how to read it is actually really hard. I guess you could say that the book is about that: learning to read linguists, poets and scientists’ discussions of vowels in a way that illuminates how we sense them.