In the developing world, rent-to-own business models offer opportunity, study finds

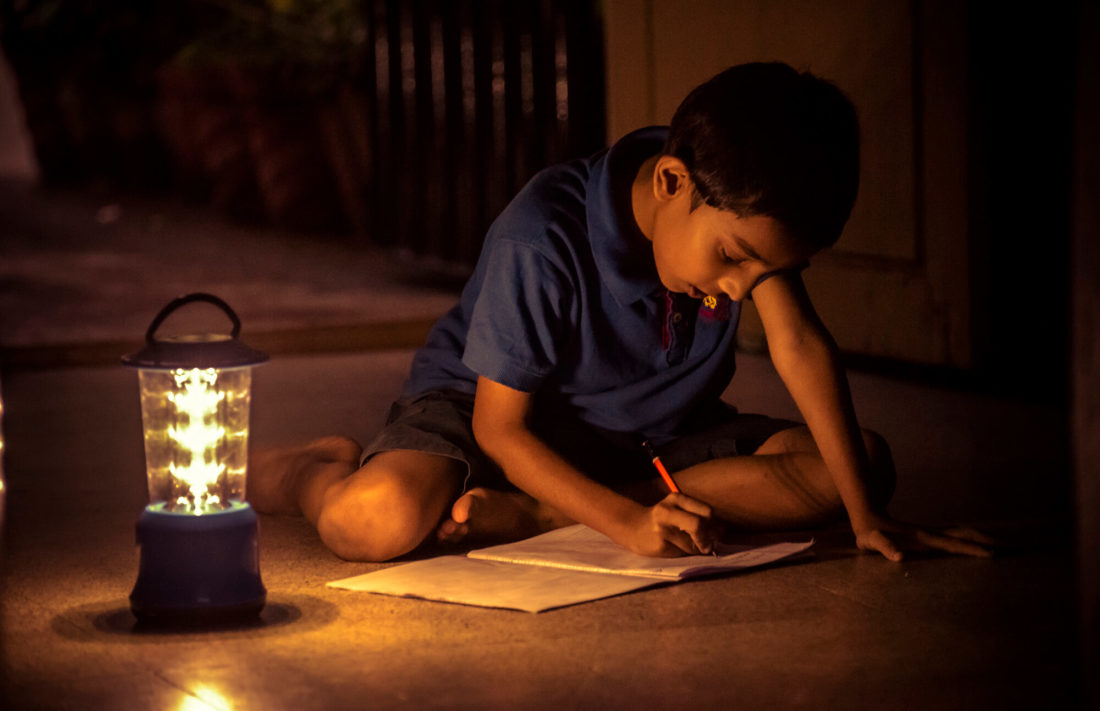

More than a billion people worldwide lack access to electricity, and even a $15 solar lamp is beyond the financial reach for many of them. Yet businesses have found a way to reach this very-low-income market through rent-to-own programs that combine incremental payments with technology to monitor and lock out non-paying customers.

A new paper by Asst. Prof. Jose Guajardo is the first to analyze how usage and payment behavior interact in rent-to-own business models and what works when serving customers in the developing world who have no savings and no credit history. The paper was recently published in Production and Operations Management.

“For low-income people in many parts of the world, it’s almost impossible to acquire products like solar lamps or cookstoves up front,” says Guajardo, who has studied service business models for a range of goods, from aircraft to solar power systems to cars. “This innovation reduces that barrier, giving people the option to make small payments over time, and using technology to enforce good payment behavior.”

What Guajardo found is that higher use is associated with higher rates of payment, payment flexibility can backfire and reduce engagement, and that business analytics models based on early information are helpful in predicting good customers.

Rent-to-own models have long been popular in Western economies to help people buy furniture and consumer electronics, and they’re gaining widespread traction in the developing world.

In a project that received partial funding from the Fisher Center for Business Analytics, Guajardo partnered with a company that sells off-grid energy products in countries such as Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and India.

Customers—who are mostly farmers—bought a $15 solar lamp, paying about 20% to 26% up front and making subsequent payments to a local agent over five to 10 weeks. Use of the lanterns is monitored and can be controlled remotely, with customers receiving text messages when a payment is due. When a payment is missed, the lantern can be locked, but customers who resume payments regain access without paying interest charges.

The paper includes three main findings:

- People who used the lanterns more heavily were more likely to make their payments on time—that is, an “engagement effect.” Drops in usage were associated with late payments.

- Customers who bundled their payments, paying for more than one week up front, ended up using the lanterns less. This counterintuitive “bundling effect” indicates that increased payment flexibility does not necessarily improve overall usage. This was perhaps because customers didn’t interact as much with agents after acquiring and had less chance to get questions answered, underscoring the value of up-front training.

- Usage data is valuable to predict payment behavior. Guajardo built predictive models of payment default, and found that usage rates during the initial period can help predict whether a customer will pay. This shows that usage tracking is a valuable tool for companies seeking to reduce the risk of having to repossess one of their products.

The results provide valuable insights for both companies and non-governmental organizations, Guajardo says. “In this case it was an inexpensive solar lamp, but rent-to-own models are also being used for higher-value items such as solar home systems or cookstoves,” he says. “Usage patterns can provide a way to identify the good payers and the less good payers, and identify who is a good candidate for upselling.”