In Deportation Push, Will U.S. Scrap Constitutional Safeguards?

Habeas corpus is an archaic term, but it reflects a core value of American democracy. UC Berkeley law professor Amanda Tyler says today’s fight over government power to detain people without due process could foreshadow a historic constitutional crisis.

Over the past several months, a potential constitutional crisis has emerged in America, seemingly in slow motion. At its heart is a question: Can the U.S. government take migrants off the street, detain them and deport them without allowing an opportunity for legal challenge?

The underlying principle is the writ of habeas corpus, a dusty Latin term not widely understood, even by some top government officials. But in the view of Amanda Tyler, a UC Berkeley law professor, the question now engaging the Trump administration, Congress and the U.S. Supreme Court goes to the heart of the nation’s character as a democracy based on the rule of law.

Tyler is a constitutional law expert and a distinguished expert on habeas corpus. Her interest emerged in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, when the U.S. was aggressively detaining people — most of them not U.S. citizens — perceived as threats to national security.

The former clerk to Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg has written extensively on the topic, including two books: Habeas Corpus in Wartime: from the Tower of London to Guantanamo Bay, and Habeas Corpus: A Very Short Introduction, both published by Oxford University Press.

Tyler welcomes the growing public interest in her area of expertise. But “I wish that it were not because the idea of suspension of habeas corpus is being floated in the public realm right now,” she said. “It is a very dangerous state of affairs.”

Berkeley News: Let’s start with a basic question: What’s the underlying purpose of habeas corpus? Why is it an important idea for democracy and the rule of law?

Amanda Tyler: Our constitutional system is built around, among other things, the very foundational idea of individual liberty and protection of individual liberty.

The writ of habeas corpus for centuries has been the primary vehicle by which individuals deprived of their liberty can go to court and question or challenge the government’s actions. It has served as the vehicle through which courts have played what I would argue is their most central role — protecting individual liberty against government overreach.

Kristi Noem, the Homeland Security secretary, recently described habeas corpus as “a constitutional right that the president has to be able to remove people from this country and suspend their rights.” How viable is that argument?

Pretty much every single thing she said in that quote was wrong, if not every single thing. To offer the perspective of a professor on this, if a student gave that answer on an exam, they would fail.

She twisted what has been a vehicle for checking executive overreach into arguing that it is actually something that empowers the executive, and that is just plain wrong.

The writ of habeas corpus is, again, a vehicle by which courts constrain the executive, or rebuke the executive for overreach and oftentimes order an executive official to release a prisoner or give someone more process before you can deprive them of their liberty or remove them from the country.

Habeas corpus has been suspended on occasions in U.S. history — could you talk a little bit about that? How rare is it?

Suspension is a very, very dramatic thing because it effectively shutters the courts, and it in some cases will expand the scope of executive authority to detain individuals. For that reason, our country’s founding generation put very strict limitations on when we could have a suspension of habeas corpus.

There must be either a rebellion or invasion, and public safety must require it. Because of those strict limitations — because it’s such a dramatic state of affairs — we have only had four suspensions on the federal level in American history under the Constitution. When you couple those with suspensions that several states enacted during the Revolutionary War, you see just how dramatic the circumstances have to be.

If you stopped somebody on the street right now and said, “Are you aware our country is currently being invaded?”, they would look at you with a blank stare.

The primary examples are the British invading the Chesapeake Bay during the Revolutionary War, the Civil War and the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941.

These are very dramatic moments in American history when the Constitution and the state itself was under attack and in jeopardy. That’s when you go to suspension. That’s where you invoke such a dramatic emergency power. But it’s not something that has ever been done lightly, nor should it be.

Was a suspension of habeas corpus required or invoked in the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II?

I’m writing a book about this right now. During World War II, there was only a suspension in effect in the Hawaiian Territory — Hawaii was not then a state. And it was enacted pursuant to a special procedure whereby, under the Hawaiian Organic Act, the territorial governor declared martial law and proclaimed a suspension the afternoon of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and President Roosevelt approved of that proclamation.

The Organic Act preceded these events by decades, so Congress never in real time confronted the issues. Notably, though, Congress and the president and members of the Justice Department discussed potentially suspending habeas in order to legalize the detention of Japanese Americans. Ultimately, no such action was taken.

At the time, the attorney general of the United States, Francis Biddle, recognized that under our constitutional tradition, the government cannot detain a citizen outside a criminal trial based solely on suspicions of disloyalty.

But ultimately, he and his department defended what happened under Executive Order 9066 as it unfolded and led to the mass detention of some 120,000 Japanese Americans, two-thirds of whom were citizens born in this country. And so that’s a very, very important period. All of this was done in blatant violation of the Suspension Clause, the habeas clause in the Constitution.

This episode highlights just how important it is to have a check on executive authority over individual liberty. Without such a check, horrible injustices can happen.

One more thing is important to underscore here: It was because of a habeas action brought by a Japanese American woman named Mitsuye Endo that went all the way to the Supreme Court that the president finally closed the camps.

Stephen Miller, one of President Trump’s top advisers, has talked directly about suspending habeas corpus. What’s your understanding of why the administration might want to do this?

It’s hard to know for sure if Stephen Miller really is floating this possibility or if he’s just playing to the press and/or trying to use his position and his voice through the press to influence the courts.

The administration clearly is very upset with a number of decisions that have come down in the lower courts and even at the Supreme Court, and I think the agenda of the administration is to ideally win their position in court.

For the moment, though, let’s take him at his word. If the White House were to suspend habeas corpus, what might that look like? What would it require legally? Would it have to be narrowly tailored to a specific “invasion,” such as the invasion they’ve alleged by members of the Salvadoran Tren de Aragua gang? Or could it be a blanket suspension?

Those are such great questions, but there’s not a lot of evidence, historically and judicially, on how the Supreme Court might answer them. What we do know are some of the basic building blocks of how suspension is supposed to function. And the first principle is we can’t have a suspension without a rebellion or invasion where public safety requires it.

We know historically that we’ve typically defined rebellion or invasion as something pretty darn serious. Something on the scale of the Civil War. Something on a scale of bombing Pearl Harbor and the threatened invasion of the Japanese. Something on the scale of the British invading during the Revolutionary War.

The second major issue is who can suspend it. And this is very important because the Constitution recognizes a power to suspend habeas, but it does so in Article I of the Constitution, the article that sets forth all things related to Congress.

Suspension, going back to its very creation in 1689 by English Parliament, is a legislative power. It has always been exercised as such. The first suspension, in fact, passed by Parliament in response to a request from William of Orange, who’d newly ascended to the English throne because he asked for extra emergency powers to detain the Jacobites who were plotting to retake the throne.

It’s how Anglo-American legal tradition always thought about suspension until the Civil War.

Some analysts cite Lincoln when they’re trying to prove that the executive branch does have this power.

President Lincoln did initially proclaim several small suspensions in the early weeks of the war before Congress assembled, then went on to declare a nationwide suspension ahead of Congress.

But if you take a step back and study the full story, you see that court after court was questioning the legality of Lincoln’s unilateral suspension in false imprisonment suits. And as a result, the Lincoln administration went to Congress and said, “We need you to pass a suspension to give us legal cover.”

The courts have no one but the executive to carry out their judgments. And if the executive isn’t honoring them, then we’re in deep trouble.

After Congress did so in 1863, Lincoln proclaimed a new nationwide suspension citing Congress’s act as the basis of his authority, all but conceding that he had behaved unlawfully.

When you get to the many additional really hard questions — Can a suspension be nationwide? Does it have to be narrowly tailored? Can you target particular ethnic groups or racial groups or religions? — there is very scant authority from the courts.

Think about a scenario where the White House says, “We’re announcing a broad suspension of habeas corpus. This allows us to detain or deport people without due process.” Would that put the U.S. automatically into a constitutional crisis?

The founding generation recognized that there would potentially be extreme situations where we might need this power. And that’s why they went ahead and included it in the Constitution. But if this administration were actually to invoke such a power, or attempt to invoke the power, it would put us in a very rarefied state of affairs, with potentially very dramatic ramifications.

I would say we would be in a crisis only if the courts didn’t second-guess such an invocation. First, because it doesn’t involve Congress taking the lead on the major decision at hand, which is Congress’ role. And second, because I don’t think the so-called invasion of the Venezuelan gang is even remotely on par with what the founding generation had in mind or any of the historical examples in play. It’s just not even remotely close.

If you stopped somebody on the street right now and said, “Are you aware our country is currently being invaded?”, they would look at you with a blank stare.

Now, there are prominent jurists and scholars who have argued that if Congress were to declare something to be an invasion and suspend habeas corpus on that basis, that is not a question the courts could second-guess. Two jurists who have said this in a post-September 11th case were Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas. There are others who subscribe to that position.

I have argued in my own scholarship that that is a very dangerous position.

Let’s continue this exercise of imagining. Suppose the White House has, to some broad extent, suspended habeas corpus. In the current environment, can we be sure what the Republican Congress would do? Or what the Supreme Court would do?

Presumably, if the administration were serious about this, the goal would be to stop courts from second-guessing the removal of individuals, so as to empower the administration to remove people more quickly and swiftly without having to answer to a court. Congress could rebuke that very plainly, making clear to the extent it hasn’t already, that judicial review is warranted in these circumstances.

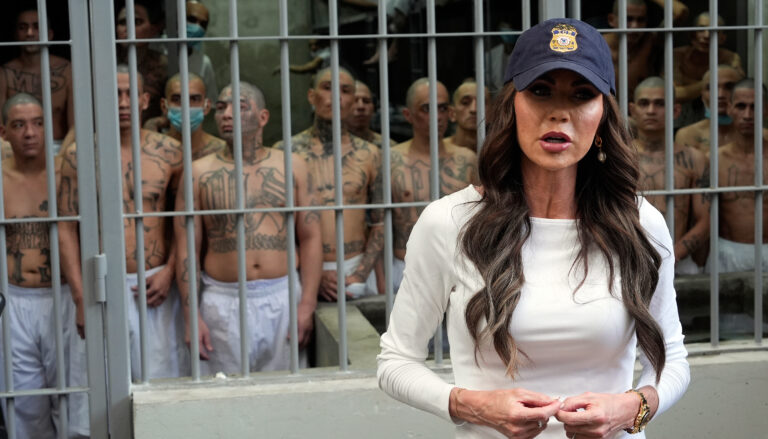

The Supreme Court has already issued three related emergency decisions in habeas cases involving individuals having been removed or under threat of removal with respect to the president’s invocation of the Alien Enemies Act, as well as removal to the notorious El Salvador prison. So all of these issues would come back to the courts in a new posture, but with all the same stakes.

The court is populated by nine justices who care very deeply about history, and I would hope that they would look to that history to see that there is overwhelming evidence to support the proposition that this is a legislative power — it was by its creation, by its origins, and it’s only at the time of the Civil War that this proposition is ever questioned.

I would hope that in studying that history and thinking about how suspension fits into our constitutional framework, a court today would view this as not a hard question and would rebuke any such executive action.

The founders also placed the power of war with Congress, and yet we know that presidents wage war without congressional approval. Isn’t there a possibility that the administration would test the bounds and say, “The Supreme Court has said no, and Congress hasn’t authorized this, but we’re going ahead anyway”? If that did happen, where are we then?

I don’t know what the administration’s real in-game objective is here or whether there is any serious discussion of suspension. My supposition is that there isn’t, that there is an intention to try and influence how courts act going forward. There is a very careful sort of dance going on between the courts, and particularly the Supreme Court and the administration, right now.

There’s one habeas case involving a man named Mr. Abrego Garcia, who by the administration’s concession was mistakenly removed from the U.S. and sent to the prison in El Salvador. On the emergency docket, the court took up his case and directed the government to “facilitate” his return. The administration has all but refused to do that.

The president in a press conference said something to the effect of, “Oh, I could do it if I wanted to, but my lawyers are telling me not to.” This is a very alarming state of affairs, particularly where it intersects with individual liberty. And so I think it’s fair to say the courts are already being tested.

Whether the administration goes even further and pushes back or resists additional decisions from the courts is anybody’s guess, but if we continue down this path, where it leads us is a very, very bad place.

The separation of powers and our constitutional structure — and our Constitution itself — only work if the branches of government respect the rules. The courts, in particular, as Alexander Hamilton reminded us at the outset, have neither force nor will, only judgment. They don’t have an army.

The courts have no one but the executive to carry out their judgments. And if the executive isn’t honoring them, then we’re in deep trouble.

The interview with Berkeley News has been lightly edited for length and clarity.