With Defiance and Solidarity, Berkeley’s Ukrainian Scholars Respond to Invasion

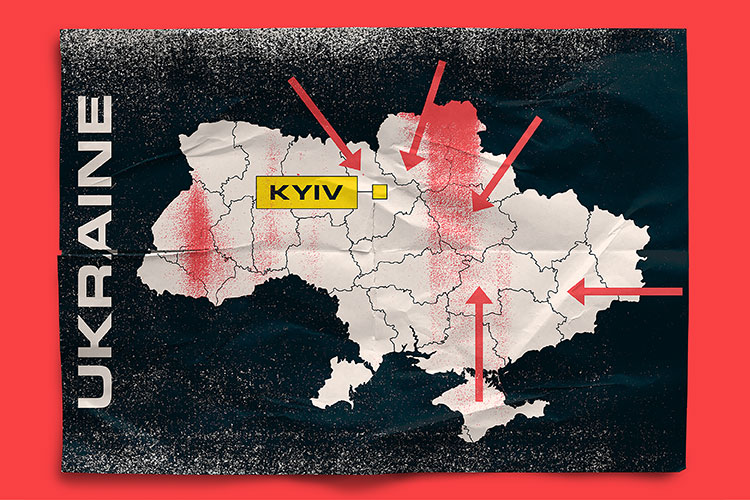

In the hours immediately following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Berkeley News asked Ukrainian faculty and students at UC Berkeley for their reactions. Their thoughts ranged across issues of family, geopolitics and justice, but each of them, in their own ways, expressed shock and defiance — and hope that the global community would rally to protect democracy and freedom.

‘We stand with the Ukrainian people in this hour’

A statement from the UC Berkeley Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures:

The tragic events unfolding in Ukraine place a special burden of responsibility on those of us who teach the languages and cultures of Russia, Eastern Europe, and Eurasia. Some of us were born in the region; all of us have long-standing ties to friends, family-members, and scholars living there.

As citizens, educators, and scholars we unequivocally condemn this war unleashed by Russian forces on Ukrainian territory. We stand with the Ukrainian people in this hour. We express our solidarity with the citizens of neighboring states – from Belarus, Poland, Moldova, the Baltic, Central Asia, and the Caucasus – who stand for peace, freedom, and the right to resist domination by any world power.

We offer our support to those in Russia who oppose this act of aggression, one that risks plunging the post-Soviet region, and with it the entire world, into a global crisis.

We stand in solidarity with our students from the region who are devastated by these events and are ready to support them.

In solidarity with people ‘who oppose this war and push for truth’

A statement from the UC Berkeley Institute of Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies (ISEEES):

The Institute of Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies at UC Berkeley condemns Putin’s campaign in Ukraine. The attack is founded on disinformation and bungled interpretations of historiography — from 882AD to the present. ISEEES stands in solidarity with all the people of Ukraine and Russia who oppose this war and push for truth and transparency during these dark times.

As scholars and students of this region, we at ISEEES will continue to do our best to provide factual and truthful information to help better understand the issues facing the region.

‘I am afraid for the whole world order’

I do not have close, immediate family in Ukraine — my mother died from COVID last year. I did hear from old school friends who said that they are under attack and they fear for their lives. My Russian friends are against this invasion.

I am baffled by all of this as I do not see any economic gains for Russia — only losses, especially for Russian people. I do not know what motivates President Putin, but I hope that he is still a rational thinker. I do not think that Russia has the military capacity to hold on to Ukraine, so I think it will carve some strategic parts of Ukraine, destroy some of its military infrastructures and then pull out.

How should the U.S., Europe and their allies respond to this invasion? I am a pacifist, so I am for the non-interventionist approach like economic sanctions. However, I am concerned about the pain regular people will have to endure due to these sanctions.

I am afraid for the whole world order unraveling if this is allowed to escalate.

— Dmitry Livdan, associate professor of finance, Berkeley Haas

‘I just hope the world helps us succeed’

My family and some friends are staying in Kyiv. They woke up early in the morning from hearing explosions and spent the day staying in lines for the necessary medicine, food and water, accompanied by the constant sound of sirens and air raid alerts. Many Kyiv citizens left the city. Many others stayed, and are hiding in subways or other bomb shelters.

What motivates Putin? As an economist, I apply the notion of rationality to predict another agent’s actions — whether it is an economic model or political campaign. However, with Putin no prediction makes sense, because given his previous actions, this man lives in his own world, not related to the real one — the world of Soviet Union, built on suppression and terror.

The economic sanctions against Russia are strong, but I’m afraid they will not stop him. He understands nothing except brute force, and treats all other attempts to rein him in as manifestations of weakness and fear of Russia. My only hope is that there are enough thinking people in Russia who will rebel against senseless violence.

In any case, with all my heart, I believe in the Ukraine army, which is already exhibiting strength, bravery and skill in not letting the invader occupy our territories in a blitzkrieg, as was apparently planned. We Ukrainians — we will not let Putin win.

— Anna Vakarova, second-year PhD student, Department of Economics

‘There are no sanctions too harsh for deterring death’

I was born in 1991, when Ukraine declared its independence and the Soviet Union collapsed. All my family is still in Ukraine. They are not leaving. It is their home.

I’m still trying to process what’s happening because it’s unbelievable. I’m still in shock. Seeing how the situation is evolving, I feel devastated. The war is unprovoked and unjustified. But on the other hand, I believe that Ukraine will remain in its current borders because the people of Ukraine and the Ukrainian government are doing all in their power to fight the attacks.

It’s all about Putin and his vision of a Russian empire. He’s a sick man trying to extend the boundaries and assert the power of his country at any cost. I feel angry about the slow response of the international community because this is the crucial force that can stop Russia.

Russia cannot take Ukraine just within one day. Maintaining war is costly. Russia has some financial reserves, but they rely on crucial relationships with the West for the economy. So cutting off all relationships is really crucial.

Imposing broad sanctions and isolating Russia economically also can help to make Russians pay attention to the war. If more Russians understood that the war has nothing to do with Russian interests, they would weaken Putin’s power from inside the country.

There are no sanctions too harsh for deterring death.

— Vitaliia Yaremko, fifth-year Ph.D. student, economics

‘Repeated attacks, repeated assaults from a bad neighbor’

My parents are from Kharkiv, the border city that was the first to be attacked. In 1991 they were busy having a child and then the regime changed. It had been the Soviet Union, but it became Ukraine the next day. They immigrated in 1995, part of a wave of Jewish refugee immigrants. I was the first one born here. We are very fortunate.

But I’m disturbed. I feel for the people who are suffering — it’s absolutely unjustified. It’s painful to see these people go through it time and time again, repeated attacks and repeated provocations and repeated assaults from a bad neighbor.

We have cousins in Russia, and they’re saying that Putin is looking for Ukrainian spies everywhere across Russia. Everyone is confused, and the Russian public doesn’t really understand the justifications for war.

Putin’s popularity has been falling for the last 10 or so years, and he’s especially losing power with the existing middle class in Russia — the educated, possibly lawyers and doctors, the non-elites who don’t necessarily benefit from his policies. Ukraine is the example of a state that could exist without an autocratic leader.

One of my mother’s friends in Ukraine said, ‘Well, whatever happens, are the trains running? I need to go to work. I need to live.’ I feel like that’s something that’s been pretty common. For the individual people, life has to go on.

— Anton Bobrov, senior, economics and statistics

‘This is not just about Ukraine’

It’s hard to describe this for an American audience, but think about Pearl Harbor or 9/11. It’s the same sense of shock and disbelief. This will go down as a day of infamy.

One thing that’s clear is that the Ukrainian armed forces — and more generally, the Ukrainian state — is not going to fold. They’re not going to lay down arms. The fight will go on for many days, many months maybe. And even if Russian forces overrun them, the resistance will be very fierce.

I hope that with the support of the international community, the Putin regime is going to pay a steep price for his crimes. He should be in The Hague, at the International Criminal Court.

This is not just about Ukraine. It’s really maybe a tipping point, something far more dangerous for everybody. If you think you can sit this out, that’s a mistake — you shouldn’t be thinking this. The experience of the world in the months and days leading into World War II should be a very, very painful lesson. You can’t hide. If there is a war this big, it will reach you one way or another.

— Yuriy Gorodnichenko, professor, Department of Economics