California rolls out first statewide earthquake early warning system

California Gov. Gavin Newsom today (Thursday, Oct. 17) announced the debut of the nation’s first statewide earthquake early warning system that will deliver alerts to people’s cellphones through an app developed at the University of California, Berkeley.

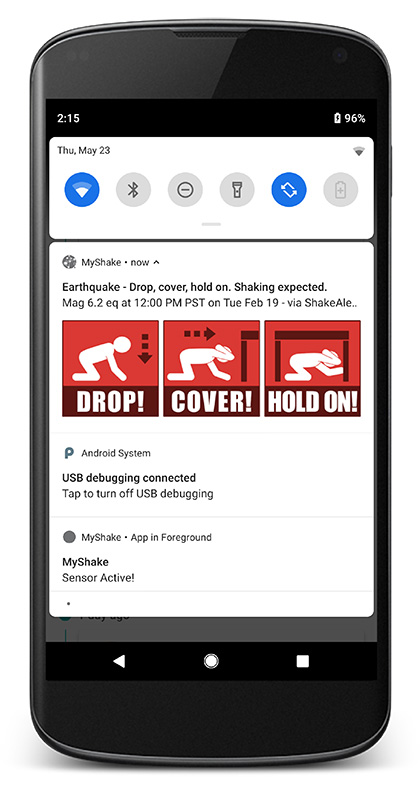

The mobile phone app, MyShake, can provide seconds of warning before the ground starts to shake from a nearby quake — enough time to drop, cover and hold on to prevent injury.

“Nothing can replace families having a plan for earthquakes and other emergencies,” said Newsom. “And we know the ‘Big One’ might be around the corner. I encourage every Californian to download this app and ensure your family is earthquake ready.”

Newsom announced the roll-out along with the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services (Cal OES), UC Berkeley, United States Geological Survey (USGS) and several state and local political leaders.

Designed by UC Berkeley seismologists and engineers, MyShake is now available for download to cellphones or tablets through iTunes for iPhones and through Google Play stores for Android phones.

The announcement was made on the 30th anniversary of the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, a magnitude 6.9 quake that damaged or collapsed buildings, overpasses and bridges from Santa Cruz to the Bay Area and led to 63 deaths and 3,757 injuries.

“Everyone asks me, ‘Are we safer now than in 1989?’ Well, now we have warnings a few seconds to tens of seconds before the shaking,” said Richard Allen, director of the Berkeley Seismological Laboratory and the Class of 1954 Professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Science.

MyShake delivers alerts from the ShakeAlert Earthquake Early Warning System operated by the U.S. Geological Survey that utilizes data from seismic networks in California, Oregon and Washington. ShakeAlert calculates preliminary magnitudes and then estimates how strong the shaking will be at a user’s location. In California, ShakeAlert has been issuing alerts of imminent ground shaking from nearby quakes for more than three years to help cities, transit systems, utilities, police departments and fire stations prepare.

ShakeAlerts are now being offered to everyone in the state of California — residents and visitors alike — through the MyShake app, as long as they allow the app to access their locations. In the event of a quake, people’s phones will deliver the audio message, “Earthquake! Drop, cover and hold on. Shaking expected.”

Considered a prototype, MyShake will be continually improved with feedback from the public to create a reliable and indispensable life-saving tool for every resident. The statewide program is administered by the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services (Cal OES) under the California Earthquake Early Warning (CEEW) Program.

“Delivering alerts remains technically challenging, both to rapidly detect earthquakes and to deliver the alerts in a timely way,” Allen said. “The reality is that warnings will arrive before, during or after shaking starts, but in all cases, they allow us to better respond and survive the earthquake.”

Earthquake-prone countries like Mexico and Japan have long had earthquake early warning (EEW) systems, with alerts typically delivered through cellphones or public address systems. For more than 10 years, seismologists from the U.S. Geological Survey, UC Berkeley, California Institute of Technology, University of Oregon and University of Washington have been developing ShakeAlert for the West Coast supported by public and private funds. Since 2016, the consortium has enlisted public agencies such as PG&E and BART to test the system.

BART, for example, now slows trains when it receives a ShakeAlert. Firehouses use precious seconds of early warning to raise their garage doors so that trucks are not trapped inside; local refineries have time to close valves to prevent spillage of dangerous chemicals and at hospitals, surgeons have time to pull their scalpels from inside patients.

Early warning, not prediction

The ShakeAlert system does not predict an earthquake, but rather provides an alert that an earthquake has been detected nearby and warns recipients that they are likely to feel shaking. It does this by detecting the first seismic waves, called P waves, from a quake, which travel faster than the much more damaging S waves. The farther you are from the epicenter, the greater the delay between P and S waves and the more advance warning you get.

While those near the quake’s epicenter are likely to experience shaking before the alert arrives, such alerts can be critical for those farther away, giving people a few seconds of warning that can save lives and property. After Southern California’s 7.1 magnitude Ridgecrest quake in July, ShakeAlert issued an alert in 7.4 seconds, which would have provided advance warning to residents more than 15 miles from the epicenter.

The ShakeAlertLA app that many Angelenos downloaded in expectation of early warning was not set to alert them to shaking from such a distant quake, and many were surprised when buildings started to sway. The threshold for local shaking has since been lowered.

As the official state EEW app, MyShake will provide the same information in Southern California as ShakeAlertLA does now in Los Angeles County. MyShake will, in addition, send back information to UC Berkeley about local shaking intensity, gathered by the cellphone’s built-in accelerometers, sensors that detect movement or vibrations. It also will give advice on how to prepare for a quake, and offer an easy way for people to provide feedback about their experiences during the quake.

Initially, MyShake will deliver alerts to people for quakes exceeding magnitude 4.5 that will produce a shaking intensity in their area greater than level 3 on the modified Mercalli scale: a threshold at which most people will feel shaking, if they are indoors, that is similar to feeling vibrations from a truck driving by on the street. Once the app has been tested, the developers plan to create a two-tier system, adding a more urgent message for those likely to experience a shaking intensity greater than 4, which is more like a truck hitting your building.

In addition to the MyShake app, the ShakeAlert system will also deliver alerts through the Wireless Emergency Alert, or WEA system — the same system that delivers severe weather warnings and AMBER Alerts. ShakeAlert computers confirm a quake and publish an alert in 3 to 10 seconds, while recent tests show that WEA has an average delivery time of about 13 seconds. MyShake has been demonstrated to deliver these alerts in as little as 3.7 seconds, meaning Californians could get an alert as soon as 7 seconds after a fault rupture begins.

“Our initial tests on the speed of MyShake alert delivery are very encouraging, but we do not know how these will change as the number of people using the app increases,” said Allen. “Rolling out the system is the only way to monitor the performance with a large number of users and further improve the system.”

Crowdsourcing information on shaking intensity

Allen leads the UC Berkeley team that developed MyShake, which has been funded since June by $1.5 million over two years from CalOES after five years of startup funding from the Moore Foundation. Allen’s team also wrote ShakeAlert’s core algorithm, which analyzes data from the state-wide network of earthquake sensors and makes the initial calculations of magnitude and estimates of shaking intensity.

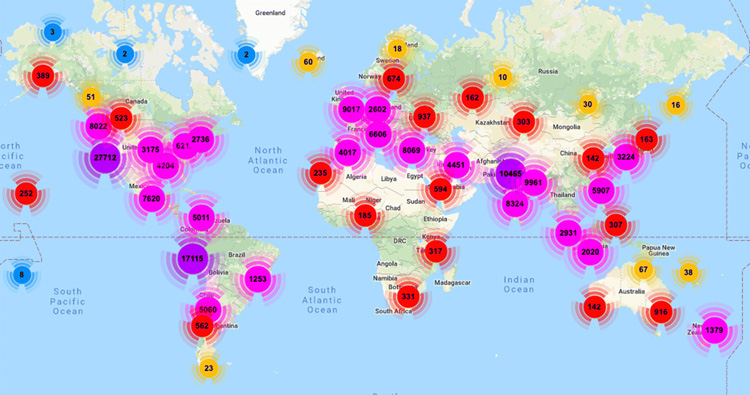

MyShake was launched in 2016 as an app that crowdsources shaking data from the sensors in a cellphone and sends that information to UC Berkeley to be analyzed. The idea, Allen said, was to use the tens of millions of cellphones in circulation within the state as a dense sensor network, which, although not as good as the scientific-grade instruments of the California Integrated Seismic Network, would augment the existing ShakeAlert system and provide valuable additional data. MyShake employs machine learning to convert this crowdsourced data into early warning of ground shaking.

“The citizen science piece is very much part of the relationship with Cal OES,” he said. “Part of what Cal OES is funding is the research to explore how the MyShake phone triggers could be used to make ShakeAlert faster. By having many more people with this app on their phones, we are going to get more data, and that, over time, could make ShakeAlert better, as well.”

Allen has a global vision for MyShake, too: bringing EEW to regions of the world that don’t have seismic networks like those in Japan, Mexico and California, but do have millions of people with cellphones. While MyShake has been downloaded 300,000 times by people in 80 countries and has recorded more than 1,000 quakes in these countries, his team needs many more users to truly test the ability of the platform to serve as an early warning network, instead of just a data collection network.

While Allen hopes that the MyShake network of citizen scientists will make both ShakeAlert and MyShake much better, for now, MyShake alerts will be based on data supplied by the ShakeAlert seismic network alone.

“MyShake is a prototype system we are rolling out, but it has the potential to save lives, reduce injuries and minimize losses in the next California quake,” he said. “By delivering ShakeAlerts to smartphones across California, we can help fulfill the potential of the California Earthquake Early Warning System.”

RELATED INFORMATION

- MyShake

- ShakeAlert

- UC Berkeley contributions to the ShakeAlert system

- Earthquake Early Warning Timeline

- The MyShake Platform: A Global Vision for Earthquake Early Warning (Pure and Applied Geophysics, Oct. 11, 2019)