California fears human, economic crisis as Washington relief talks continue

High-stakes negotiations underway in Washington, D.C., over a new round of pandemic relief funding could help California to achieve a relatively quick recovery — or, if they fail, contribute to an economic slump that lasts for years, UC Berkeley scholars say.

In a series of interviews, experts said a new COVID-19 relief package could provide critical aid to vulnerable groups as the pandemic renews its devastating surge. Millions of unemployed workers are slated to lose their benefits on the day after Christmas, and hundreds of thousands of renters could face eviction in the new year. Hard-hit small businesses, child care centers, local governments and universities also face historic financial threats.

Last March, Congress passed and President Donald Trump signed a $2.2 trillion measure — the CARES Act — to provide support to individuals, businesses and institutions hurt in the early months of the pandemic. A new round of federal aid could benefit tens of millions of Californians, the Berkeley experts said, if Republicans and Democrats can bridge deep differences to come up with a plan in the days ahead.

As earlier pandemic relief runs out, “we know poverty is increasing,” said Sylvia Allegretto, an economist at the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment (IRLE) at UC Berkeley. “We know that hunger and the incidence of hunger are increasing, especially for children and people of color. We know that homelessness by the millions will increase if we do not have another moratorium on renter evictions.”

“Right now the economy is barely holding on,” added economist Jesse Rothstein, faculty director of the California Policy Lab at Berkeley. “If we don’t pass something more, we basically take away the legs that support a teetering economy. There’s a real risk that the economy will collapse into something like a traditional recession and … bankrupt millions of people.”

A bipartisan group of moderates in Congress has proposed a $748 billion aid bill, with a separate $160 billion measure that includes financial aid to state and local governments devastated by extra expenses and lost revenues resulting from the pandemic. That’s less than half the size of the CARES Act, and with the virus accelerating and U.S. deaths surpassing 300,000, it was unclear Wednesday whether congressional leaders are still using it as a basis for their negotiations.

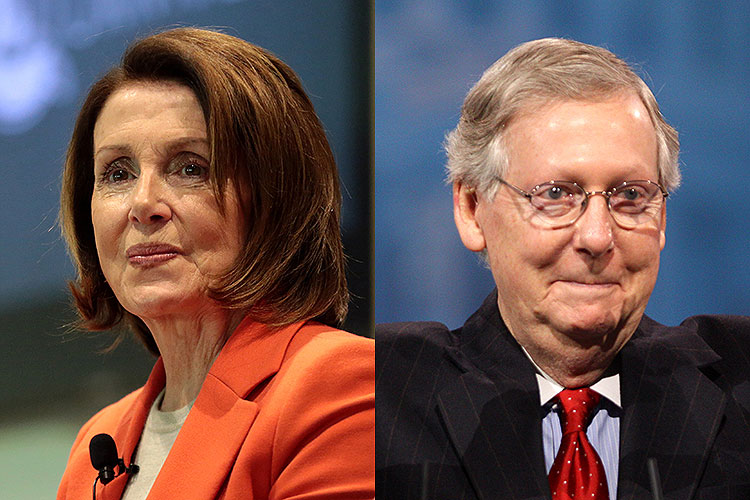

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer and House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy met until after midnight on Tuesday and indicated that they were making progress on a deal of roughly $900 billion. Sources involved in the coronavirus relief package told Politico that it would include a second round of direct payments, but would likely leave out state and local funding and a controversial liability shield to protect businesses from COVID-related lawsuits by workers and customers.

Allegretto, Rothstein and other Berkeley scholars said the congressional measure falls far short of the robust investments required to counter the pandemic’s economic shock. But, they said, funding in areas such as unemployment insurance, child care and renter protections could ripple throughout the economy, bringing important human benefits and helping to protect economic stability in California and nationwide.

A million workers could lose unemployment insurance within days

Since the start of the pandemic, nearly 45% of the California workforce has filed for unemployment insurance. When two key federal pandemic benefit programs expire beginning Dec. 26, 1 million workers will face the sudden loss of their benefits, said a report released Tuesday by the California Policy Lab.

The measure being developed by the bipartisan congressional group — the Emergency COVID Relief Act of 2020 — would extend the two federal programs for 16 weeks.

That could bring nearly $10 billion in unemployment benefits to Californians, enough to preserve or generate almost 45,000 jobs by April, the analysis found. The measure also proposes a supplemental federal payment of $300 per week in unemployment benefits. That’s down from $600 per week provided under the CARES Act, but still enough to drive $30 billion in economic activity in California before the end of April 2021.

Whether the federal government should supplement state unemployment payments or provide one-time checks to most Americans, as in the first round of pandemic relief, is the focus of intense debate.

“Unemployment benefits are targeted to the people who really need it: the people who lost their jobs,” said Rothstein. “It’s nice for everyone to get a check, but it’s not essential.”

Rothstein also noted a hidden threat: Even if a new measure is passed soon, pandemic unemployment payments will likely be interrupted because states will need time to adjust administrative systems for the program.

Hundreds of thousands of California renters could soon face eviction

Unemployment has a devastating secondary impact: People are unable to pay their rent.

“People who rent are much more likely to be in the service industry, to be front-line workers with a much higher risk of exposure to COVID-19,” said Ben Metcalf, managing director of the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at Berkeley. “Therefore, they are also in the same industries that are most likely to have been shut down or to have imposed furloughs. … Those folks tend to be lower-income, and they tend to be disproportionately Black and Latinx.”

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention declared a moratorium on evictions, but that ends in January. California has its own moratorium, but it ends in February.

The bipartisan relief measure being developed in Congress could provide $25 billion nationwide for emergency rental assistance. That aid, Metcalf said, “would be hugely important in preventing the very bad outcome of folks moving into homelessness … in the next few months.”

Without new protections, the scope of threats to California renters is enormous: A Terner Center study published in October analyzed U.S. Census Bureau data and found that since the pandemic emerged, 597,000 families had been late on a rent payment.

A study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia found that 240,000 Californians will owe a total of $1.7 billion in back rent by the end of this year.

Even if current eviction protections are extended, Metcalf said, individual renters will carry thousands of dollars in debt that will be difficult to repay to landlords. That means landlords may struggle to pay their own bills, and if the landlords can’t pay taxes, the financial stress is passed on to local and state governments.

The pandemic has driven California’s child care to the brink of collapse

The COVID-19 pandemic has put California child care providers in an impossible quandary: If they suspend operations, they lose income, and pay and profit margins already are low. If they stay open, the owners put themselves and their employees at risk of infection. Their costs rise for cleaning and protective equipment, but revenues fall as some families keep their kids at home.

“We knew the system was fragile, even before the pandemic,” said Lea Austin, director of the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment (CSCCE) at Berkeley. “By last July, we knew that about one in five providers in California had already missed rent or mortgage payments for their centers. Over a third were saying, ‘I don’t even have enough money to purchase needed supplies.’”

The result? Several thousand California programs have closed, Austin said. Thousands of skilled, but low-paid, child care workers — most of them women, and many of them women of color — are out of work. Tens of thousands of spaces for young children have been lost.

The bipartisan group of senators has proposed $10 billion in aid to child care nationwide — up from $3.5 billion under the CARES Act. If that were approved, it would help, Austin said, but it wouldn’t be enough to stabilize a damaged system.

And if lawmakers fail to reach agreement? “We would see more of the economic stress on child care workers and a collapse of the system we’re seeing now,” she predicted, “only worse.”

Local governments and schools: manage the pandemic, but cut spending

The challenge of addressing the pandemic has touched almost every government service in California — not just unemployment support, but policing, parks and schools. But federal aid for state and local governments is so controversial that congressional leaders have separated it from the main negotiations over disaster relief.

In California, the budget forecast is better than expected, largely because the tech industry continues to thrive, and more affluent workers who pay most of the state’s income taxes have been able to work from home.

But still, over the next three years the state budget deficit is expected to grow to $17 billion.

Meanwhile, the pandemic has imposed intense pressures on local governments: Tourism is down, and restaurants are limited or closed. Unemployment is high, and taxes are down. With less revenue, governments are under pressure to reduce staff or services, or both.

For schools, it costs more to provide education during a pandemic. Transit agencies, on the other hand, have seen ridership — and revenues — plunge, and they’re struggling to avoid layoffs.

“We’re in the realm of cuts to education, cuts to health care,” said political scientist Eric Schickler, co-director of the Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies. “The scale of the budget crisis in a lot of states is so big that you may just see across-the-board 5% cuts or 10% cuts.

“That could lead to a lot of job losses at the state and local level, even though we’re at a point where their services are needed and the demands are high. That could set back the economic recovery and give rise to the very harsh politics of austerity.”

Universities are dealing with historic losses — and limited support

The pandemic has imposed severe challenges on universities: Revenue from tuition and housing fees is down, but the cost of providing an education is up. Berkeley has not been immune.

Remote education, lost research, health screening, increased cleaning and other pandemic-related expenses have created new costs of $340 million at Berkeley, including a $42 million reduction in state aid. In response, the campus has frozen most hiring, cancelled regular pay increases, increased borrowing and reduced spending in other areas.

Under the CARES Act, $14 billion was set aside for universities nationwide. Berkeley received $30 million — enough to offset less than 9% of its total costs.

University officials are hoping to receive a similar amount from current negotiations in Washington. It’s not enough to resolve the financial threats, but it would help support operations and student services while reducing pressure to borrow, said Berkeley Chief Financial Officer Rosemarie Rae.

“It would create a degree of financial certainty for the campus,” Rae said. “And it would help to ensure that we are protecting our academic core and preserving jobs.”

Invest now — or pay the price later?

The need for massive investment in pandemic relief is clear to many leaders in Washington, both Democratic and Republican. But the nation is so polarized, and the political culture so paralyzed, that Berkeley experts aren’t sure whether any agreement can pass the Democratic House and the Republican Senate and win final approval from Trump.

If political will can be summoned, Allegretto is sure the U.S. can afford it. The nation has a $22 trillion economy, and with interest rates low, she believes it can invest in a new round of pandemic relief that equals or exceeds the $2.2 trillion CARES Act.

“Yes, that’s a lot of money,” she said, “but it’s going to be much more expensive if these economic problems become ingrained and then last years and years after the pandemic is taken care of.

“I’d rather think about keeping people whole, keeping small businesses whole,” she added. “We should think about how to keep poverty from rising, how to keep homelessness from rising and hunger from rising. As the richest country in the world, we are in a position to respond to this. And it’s just unconscionable that we don’t proceed as soon as possible.”