Breakthrough in designing cheaper, more efficient catalysts for fuel cells

University of California, Berkeley, chemists are reimagining catalysts in ways that could have a profound impact on the chemical industry as well as on the growing market for hydrogen fuel cell vehicles.

Catalysts are materials ‑ typically metals ‑ that speed up chemical reactions and are widely used in the synthesis of chemicals and drugs. They also are employed in automobile catalytic converters to change combustion chemicals into less-polluting emissions and in fuel cells to convert water into hydrogen.

The problem with catalysts, however, is that chemical reactions occur only at edges of or defects in the material, while the bulk of the metal – often expensive platinum – is inactive and wasted.

In an article appearing this week in the journal Science, UC Berkeley chemists show how to construct a catalyst composed only of edges and demonstrate that it can catalyze the production of hydrogen from water as readily as the edges and defects in regular catalysts.

“This is a conceptual advance in the way we think about generating hydrogen, a clean burning fuel, from water, a sustainable source,” said Christopher Chang, associate professor of chemistry and Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator at UC Berkeley. “Our new catalyst is just first generation, but the research gives us and the community a path forward to thinking about how to increase the density of functional active sites so that molecules and materials can be more effective catalysts.”

At the moment, creating these catalysts in the lab is not cheaper than using traditional catalysts, but efforts by Chang and others to simplify the process and create materials with billions of active sites on a ridged wafer much like a Ruffles potato chip could allow cheaper, commercially viable fuel cell catalysts.

“The development of new earth-abundant catalysts for water splitting is an essential component of the global effort to move away from fossil fuels and towards solar energy,” said coauthor Jeffrey Long, UC Berkeley professor of chemistry and faculty scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

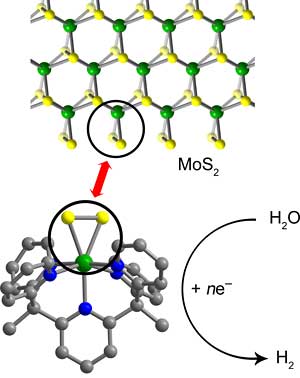

Chang and his UC Berkeley colleagues worked with a common catalyst, molybdenite, that is less expensive than platinum and of increasing interest as a fuel cell catalyst. Composed of molybdenum and sulfur (MoS2), the material catalyzes reactions like the splitting of water into hydrogen and oxygen only at the edges, where triangles of molybdenum and two sulfur atoms stick out like pennants.

“These edge sites look like little MoSS triangles, and the triangular area does the business,” Chang said.

Using complex organic synthesis techniques, Chang said he and his colleagues created a small carbon framework to hold the MoSS triangle so that “every molecule has a discrete edge site that is a catalytically active unit.”

When lots of these single-molecule catalysts were dumped into acidic water and even seawater, they generated hydrogen for several days without letup.

In future research, Chang hopes to assemble billions of these molecules on a thin, ridged wafer, maximizing the number of catalytic sites for a given volume and boosting ultimate efficiency.

“There are many other types of materials out there for which people might want to generate edge-site fragments rather than use a bulk material with just a few edge or defect sites,” Chang said. “With hydrogen being touted as a clean burning fuel that generates no CO2, creating cheaper and better catalysts has become a big and important field now. The main push is toward more earth-abundant materials than the rare metals like platinum.”

Chang and Long’s UC Berkeley coauthors are post-doctoral fellows Hemamala I. Karunadasa, Elizabeth Montalvo and Yujie Sun, and professor of chemistry Marcin Majda. Chang, Long and Sun also hold positions at LBNL. Kuranadasa is now a post-doc at the California Institute of Technology.